Original illustration for Echowall by Tse Yuet Ching.

Boxing In China's Innovators

Top technology firms in China now account for almost half of the top-20 global firms. But as these companies seek to develop globally, their close association with the Chinese government is a force that both pushes them forward and holds them back.

On September 20, 2019, the city government in Hangzhou, a coastal city in southeastern China, announced it would dispatch “government affairs representatives” to 100 key enterprises. Government officials claimed this was an “innovative measure” in “new manufacturing industry planning,” designed to provide full support to companies in dealing with a range of administrative affairs, including policy communication and project implementation. Hangzhou is one of China’s key national centers for technology companies, home to tech giants like Alibaba and Hikvision.

At a time when China’s government is strengthening its hold over all aspects of Chinese society, the announcement in Hangzhou was interpreted by many people as an intensification of controls on enterprises. Some speculated that this might be a replay of the so-called “public-private partnerships” of the 1950s, a widespread process of collectivization by which the Chinese Communist Party stripped private companies of their ownership.

Facing a climate of growing concern, the Hangzhou government later replied that the public was over-reacting, and that these so-called government affairs representatives would not affect business decisions. While it is difficult to tell how the situation in Hangzhou might unfold, the case reflects the tangled relationship between the Chinese government and important and influential companies.

Co-Dependent Giants

The rapid rise over the past decade of Chinese tech giants like Alibaba, Tencent and Huawei has been eye-popping. They have gone from being virtual unknowns to being global giants both in terms of scale and market value.

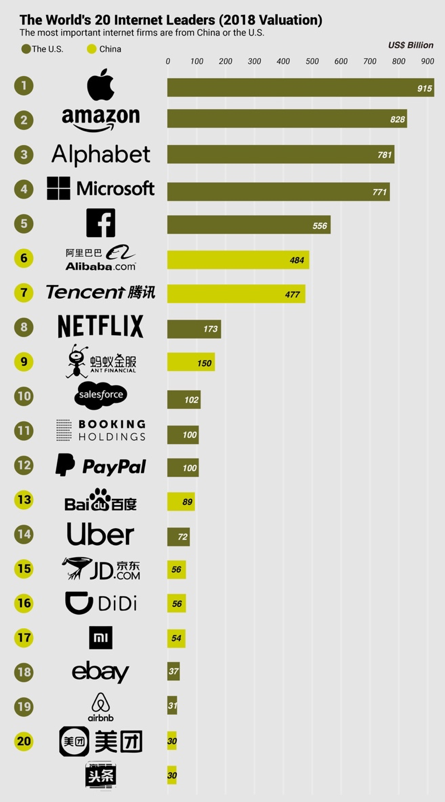

According to data from the World Economic Forum, of the world’s top 20 companies in terms of market value as of May 2018, 11 are from the United States and 9 are from China. In this respect, Europe has been entirely left behind. China’s tech champions operate around the world, providing competitive products and services.

No European companies appear on the roster of the world's top 20 tech firms by market capitalization. SOURCE: Kleiner Perkins Internet Trends Report 2018, Forbes, Company Reports.

As China’s most valued internet companies, Alibaba and Tencent are still heavily reliant on the domestic market as the base of their businesses and their primary source of profit, even though their businesses have expanded across the world. This is the chief reason why these companies must continue to bow at the feet of the Chinese government.

Further complicating the relationship, the Chinese government regularly extends special privileges to these giants, as when Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat entered the sector of payment services and received preferential treatment from Chinese monetary authorities. Mybank and Webank, the banks established by Alibaba and Tencent respectively, benefit from various policy preferences as well.

As these companies compete with transnational giants from the United States, they can trust that the Chinese government is on their side. In 2010, for example, Google was driven out of China, and the search engine giant Baidu as a result gained a virtual monopoly in the field of search engine services – a benefit unimaginable without the government assistance.

As these companies compete with transnational giants from the United States, they can trust that the Chinese government is on their side

Similarly, Tencent’s WeChat dominates the domestic market and can explore global business opportunities even as Facebook remains banned in mainland China. Similarly, Alibaba’s various businesses benefit across the board from administrative barriers and government support. In a normal market, these companies would instead face anti-monopoly actions.

As China seeks to “innovate” social and political controls through AI and surveillance, governments at every level in China are also important clients of domestic tech companies. One of many examples is iFlytek, China’s leading AI company, which relies heavily on government orders and subsidies, not least to support “smart city” initiatives, which have essentially created an industry out of China’s monitoring of its own citizens.

Video cameras like this one in an alley in the city of Qingdao are now virtually everywhere in today's China. Images by Gauthier Delacroix available at Flickr.com under CC license.

Innovating Social Controls

Domestic media reports in China have referred to smart cities as a “new wind gap” – an area, in other words, of red-hot investment. By the end of 2017, over 500 cities had either begun smart city development or had announced their intention to become smart cities. It is estimated that by 2021, the scale of this market in China will reach 240 billion euros (260 billion dollars). This will involve the building of more than 5,600 data centers, consuming 120 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity per year. This is more than current annual electricity consumption in Beijing and equal to the annual output generated by the Three Gorges Dam.

This massive market, chiefly the result of government financing, has attracted an influx of private companies hoping to profit from urban security and surveillance. The four most competitive companies in the field at present are Ping’an, Alibaba, Tencent and Huawei, referred to lately as “PATH.” Other players include JD, ZTE, Baidu, and iFlytek.

The fastest growing areas within the push for smart cities have been “smart surveillance” (智慧安防), “smart traffic” (智慧交通) and “smart communities” (智慧社区). The government pays for these programs, while the police monitor society and control the data generated in the process. Consider that officials in Shanghai, one region leading the smart city push, have said that the development of “smart police should come before smart city [development],” and that the emphasis “must be on constant vigilance, with prevention [of problems] being of foremost importance.”

According to one domestic study, the principle and most crucial aspect of the “smart city” concept is security, the so-called “safe city.” The concept of the “safe city” has developed in a number of phases in China.

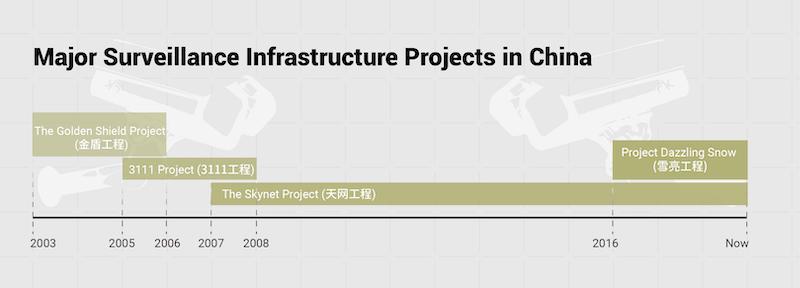

2003 to 2006: The introduction of the Golden Shield Project (金盾工程), a project to digitalize the public security bureau and build local area networks completely isolated from the public internet.

2005: The start of Project 3111 (3111工程, an engineering project organized by the Ministry of Public Security to advance construction of urban security surveillance.

2007: The beginning of SkyNet (天网工程), a digitalization project consisting of GIS (Geographic Information Systems) mapping, the development of software and related equipment to capture, transfer, display and control images that enable monitoring and recording of specified areas, particularly urban areas. This project was initiated by Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission (the CCP’s political and legal affairs office), and implemented by the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Information Industry.

2016: The introduction of “Project Dazzling Snow” (雪亮工程), also known in English as the “Sharp Eyes Project.” This is a national public security surveillance system focusing on the countryside in China, with command centers at the county, town and village levels to be connected to digital surveillance networks under a grid management system.

China has already become a surveillance state, with big data and AI technology integrated into a comprehensive surveillance system.

Bing Xu, a co-founder of the Chinese tech firm SenseTime, boasts at a 2018 conference in Las Vegas that his company powers 'the world’s largest surveillance network." Images by Steve Jurvetson available at Flickr.com under CC license.

These initiatives, which are being backed with massive technological support, aim to construct an omnipresent, seamless and controllable surveillance system. Today, all of China’s major cities have camera surveillance systems in place. It is estimated that by 2022, less than three years from now, the number of surveillance cameras in China will further increase by 213 percent, reaching roughly 626 million surveillance cameras in operation – meaning one camera for every two Chinese people.

China has already become a surveillance state, with big data and AI technology integrated into a comprehensive surveillance system. In the process, giant tech companies like Huawei, Hikvision, Alibaba and Tencent have each become important technology providers.

Aside from real-time surveillance of its citizens, China is pushing ahead with the establishment of its so-called “enterprise social credit system.” The government’s ultimate goal is to build a central database that can be used to track, record, publicize and share credit ratings and credit records of Chinese companies, the database serving as a risk prediction and warning mechanism to prevent corporate misconduct. Companies with low credit ratings would be subject to various forms of penalty.

Official statements have sought to explain that while credit agencies in the West publicize corporate financial information and leave it to the market to deal with companies, “China’s social credit system is a tool used [by the state] to govern the economy and the society.” Some legal professionals in China have criticized the government’s overarching role in this process of penalization, arguing that in this case administrative policies are upstaging the law. But the “enterprise social credit system” has already the final key stage of its development. By September this year, it had encompassed 33 million companies, with its sights on comprehensive coverage of all private companies in China.

All companies operating in China must take this grading system seriously and abide by it, lest they be expelled from the market. Just as with the systems monitoring China’s citizens, major tech firms like Huawei, Alibaba and Tencent are heavily invested in this grand project to collect extensive data on private companies.

Monitoring the Surveillance Companies

Naturally, those companies applying their innovation capabilities to help the government achieve its goal of comprehensive surveillance cannot themselves escape the government’s watch list.

Aside from the so-called “government affairs representatives” mentioned at the outset of this article, the CCP has pushed the establishment of party organs in both private companies and foreign-owned companies. CCP organizations exist in nearly every private company of a sufficient scale in China. In the private sector, internet companies and tech companies are more likely than companies in other sectors to have CCP party branches. Alibaba has around 200 party branches nationwide. Tencent has 89.

In a list of top 100 distinguished contributors during the reform period in China, published in the Party’s official People’s Daily newspaper, Alibaba founder Jack Ma was introduced as a Party member. This was the first time this information about Ma had been released, and the story became international news. It is by no means a secret, however, that many of China’s well-known entrepreneurs are members of the Party, including SANY Group founder Liang Wengen, Dalian Wanda’s Wang Jianlin, Evergrande Group’s Xu Jiayin, Lenovo’s Liu Chuanzhi and Huawei’s Ren Zhengfei.

Alibaba founder Jack Ma is all smiles at the 20th Anniversary Schwab Foundation Gala Dinner on September 23, 2018. Ma resigned as executive chairman of Alibaba in September 2019. Image by World Economic Forum Foundations available at Flickr.com under CC license.