Shanghai's Pudong District, built from only the late 1990s, has become a symbol of China's economic prowess. Image by Boris Kasimov available at Flickr.com under CC license.

Efficient China

One of the most persistent myths about China is that its system works with great efficiency, enabling concerted action and long-term planning. But such rosy assessments overlook key costs – not least to the rights and protection of citizens.

For some, words like “paralysis” and “gridlock” have become synonymous in recent years with political decision-making in the European Union and many of its member states. There is an abiding sense in certain circles, whether among politicians, academics or ordinary voters, that shortsightedness and political wrangling in the representative democracies of Europe has kept leaders from making decisive choices. For some, China, with its apparent ease in mobilizing people and resources to define and accomplish necessary tasks, provides a practical example of a system that can cut through the nonsense and get straight to solutions.

Key Points:

China’s centralized governance is sometimes seen as a major advantage. But this overlooks the immense costs and two key questions: How does the system derive its huge resources? Why does the government enjoy such powers of enforcement?

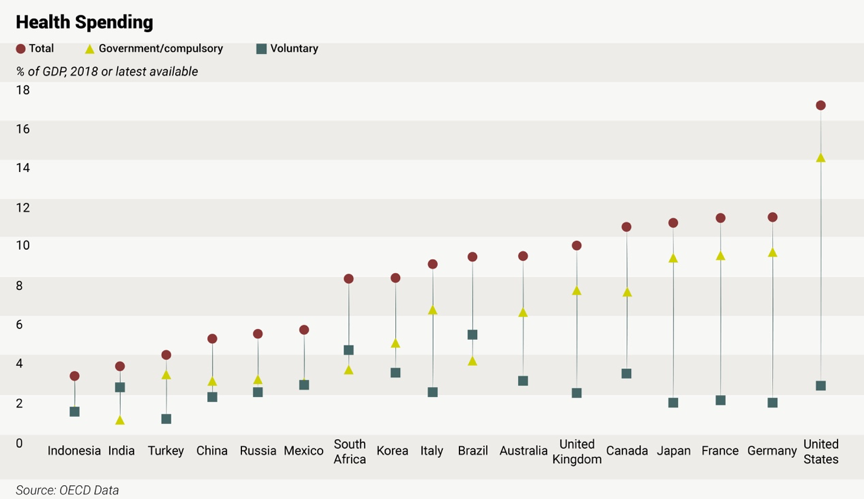

High taxation, low benefits. If non-tax revenues collected by the government are considered in addition to formal categories of tax, China’s tax burden is likely 35 percent to 40 percent of GDP, surpassing many high-welfare European countries. Yet, the quality of public service and social security lag far behind standards in Europe.

Low human rights standards. Unfairness in China’s welfare system, lack of access to healthcare (particularly for those without urban registration), forced land acquisition and violent property demolition and other common problems lower the cost of development for China’s government.

Debt for development. Since the 1990s, local Chinese governments have rapidly built a "GDP machine" that leverages borrowing for development. This has led to huge level of so-called implicit debt. Of the 29 provincial-level administrative divisions in China for which statistics were available, 21 had debt levels exceeding 150 percent.

One vocal proponent in support of China’s way, for example, has been Jørgen Randers, a Norwegian professor of climate strategy who is also a member of the Club of Rome, an organization comprising a range of experts and current and former politicians addressing key global issues.

Randers was one of the authors of the 1972 report The Limits of Growth, which was commissioned by the club to look at humanity's ecological footprint. In an update to that report published in 2012 (PDF here), Randers was bullish about the role of China and the efficacy of its centralized system, predicting that it would become the future world leader owing to the ability of its “strong government” to lead on issues like climate change.

At one point, Randers writes in his report: “I think we will see 40 years down the line that it was the Chinese who did, in the end, solve the climate problem for us – through collective action. They will produce the electric cars and the technologies we will need, and they will implement them in China through centralised decisions.”

Randers has repeatedly emphasized in his interviews in recent years that China has institutional advantages and efficiency that western countries do not have. China, he says, can concentrate power to make decisions. Meanwhile, China has the willingness and the ability to direct resources and investment towards the necessary fields. Randers has spoken of Chinese Communist Party as an “enlightened dictatorship” capable of ruling “above the popular mandate.”

U.S. entrepreneur Elon Musk, the founder and CEO of two companies valued at over 100 billion US dollars,has praised Chinese efficiency in much the same way. “China's progress in advanced infrastructure is more than 100 times faster than the U.S.," Musk wrote in a 2018 post on Twitter, accompanied by a short video about how a railway station in China could be built within nine hours.

Early 2019, while meeting China’s Premier Li Keqiang, Musk again praised the speed and efficiency of China’s development, and said that it was hard to imagine that anywhere else a car factory could be completed and opened in such a short time like the Tesla plant in Shanghai.

Such praise of Chinese efficiency generally focuses on two aspects: first, that the Chinese government has ample resources to put in; and secondly, that the Chinese government has formidable powers of administrative enforcement, which are not restricted by such forces as public opinion.

Elon Musk praises China's speedy building of infrastructure in a 2018 Twitter post.

But there are two crucial questions we should think seriously about before we reach conclusions about the Chinese experience and extend it to possible lessons for the world. First, where does all of this money come from? And second, why does the government enjoy such powers of enforcement.

Before we answer these key questions, it is impossible to draw conclusions about whether or not these administrative superpowers are really solutions to the problems the world faces.

Following the Money

Let’s begin first with the key question of where the resources of the state come from.

The results of China’s 40-year opening and reform policy are certainly eye-catching. Brand new high-speed trains, cities glittering with modern buildings, sprawling subway systems – all of these are apparent wonders people take delight in talking about. Official data has shown that China’s urbanization rate jumped from 30 percent in 1996 to 60 percent in 2018. In 2017, China’s completed infrastructure investment was nearly 2.6 trillion dollars, about 21 percent of the nation’s GDP. Aside from domestic investments, China has directly invested over 90 billion dollars from 2013 to 2018 in countries that are part of its “Belt and Road Initiative,”the massive global development strategy that is a centerpiece of China’s foreign policy. The major part of these infrastructure investments are government projects.

But where does all that money come from?

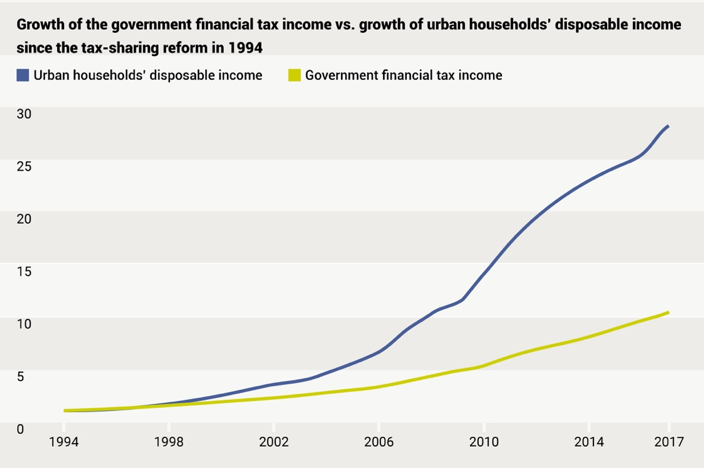

Taxes and Fees Without Consultation

China’s financial revenue expanded rapidly in the past decades, corresponding to the fast growth of China. Every year, the growth rate for financial revenue has been higher than the GDP growth rate, and the growth is also much faster than the increase of personal income. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Chinese urban households’ disposable income increased 9.41 times from 1994 to 2017, but during the same period tax revenues increased 27.16 times – and this does not even include non-tax income, land leasing revenue (this is revenue for land sales], extra-budgetary revenue, and social security income.

The results of China’s 40-year opening and reform policy are certainly eye-catching. . . . But where does all that money come from?

So, what exactly is the Chinese government’s total income?

The results differ widely depending on how we make the statistical calculations. The government often claims that China’s tax burden is low in comparison to other countries internationally, but this claim factors in only government income from those payments clearly identified as “tax.” However, one thing about the Chinese government’s fiscal system is that the tax burden is not just about tax — and the sources of government revenue are extremely complicated.

Source: Caixin Media.

An Tifu, a finance expert, concluded in 2010 that aside from fiscal revenue or budgetary income (also called in Chinese “first-tier income,” of which the principle part is tax), Chinese government revenue also includes extra-budgetary revenue (“second-tier income”), and non-institutional revenue (“third-tier income”), as well as revenue from land sales (“land financing”), and so on. Aside from 18 nationally recognized categories of regular tax – the primary source of budgetary income – there are thousands of other names used in jurisdictions across the country for collecting fees, fines, funds, apportionment, and other income, comprising extra-budgetary income.

These non-tax revenues are not only legion in terms of types and categories, but also translate into vast amounts.

According to data from 2017, if we only calculate macro tax burden by the narrowest definition (tax/GDP), China’s rate is 17.5 percent. Yet the disclosed macro tax burden in a broader sense (general government revenue/GDP) is as high as 27.6 percent. According to analyses from multiple parties (for example, An Tifu, 2010), China’s generalized tax burden is 35 percent to 40 percent of GDP if other real government revenues are added, reaching and even surpassing many high-welfare European countries. Yet, the quality of public service and social security lag far behind standards in Europe.

The 18 Types of "Regular Tax" in China:

Taxes on Goods and Services: value-added tax (增值税), sales tax (消费税), business tax (营业税), vehicle purchase tax (车辆购置税), customs tax (关税)

Income Tax: corporate income tax (企业所得税), personal income tax (个人所得税)

Property and Use Tax: land appreciation tax (土地增值税), property tax (房产税), urban land-use tax (城镇土地使用税), arable land occupation tax (耕地占用税), contract tax (契税), resource tax (资源税), vehicle and vessel use tax (车船税), stamp tax (印花税), urban maintenance and construction tax (城市维护建设税), tobacco tax (烟叶税) and tonnage tax (船舶吨税).

Behind these surging government revenues that depress the incomes of China’s residents looms the fact that tax collection in China is fundamentally undemocratic and not subject to rule of law.

The irregularity of taxation complements the reality that the government's legislation and administration powers are not divided and that the people have no democratic power.

From the perspective of the central government, the 18 regular taxes were originally published in the form of administrative regulations of the State Council, rather than formal legislation by the legislature. The National People's Congress, which is nominally responsible for legislative taxation, is nothing more than a rubber seal and lacks the function of representative democracy. The public has no power and channels to participate in the decision of taxation and the determination of tax rates.

From the perspective of local governments, since the tax-distribution reform in 1994, “high-quality taxes,”a term often used to refer to forms of tax that provide stable and dependable revenue, have all been collected by the central government. As local economic growth has been a core calculation in the index of promotion of officials within the system, local governments at all levels have tried every means to “scrape and scramble” for various sources of revenue.

Local governments at all levels have tried every means to “scrape and scramble” for various sources of revenue.

As a result, the commercialization of public services has become a common phenomena – meaning that citizens and businesses are paying out of pocket, in addition to the formal tax burden, for the government to do its job and provide basic services. To provide one example, expenses related to public services should be accounted for in the government budget, but many local governments impose additional administrative fees on municipal services such as the installation of street lamps and building of roads.

Debt for Development

The obsession with GDP growth as a performance indicator for local government officials has also resulted in the creation of a whole system of investment financing as officials seek the means to stimulate GDP.

GDP growth targets account for a large share of the performance assessments conducted for local officials in China. GDP increases are all about trade, consumption, and investment. The growth of trade and consumption is difficult to achieve in the short-term, as they depend on market conditions and people's income. Therefore, investment has become the most important means for officials to stimulate local GDP growth, and the investment projects with the most political points and potential value all generally have to do with infrastructure.

Since the 1990s, local Chinese governments have rapidly built a "GDP machine" that leverages borrowing for development. Here is how the machine works:

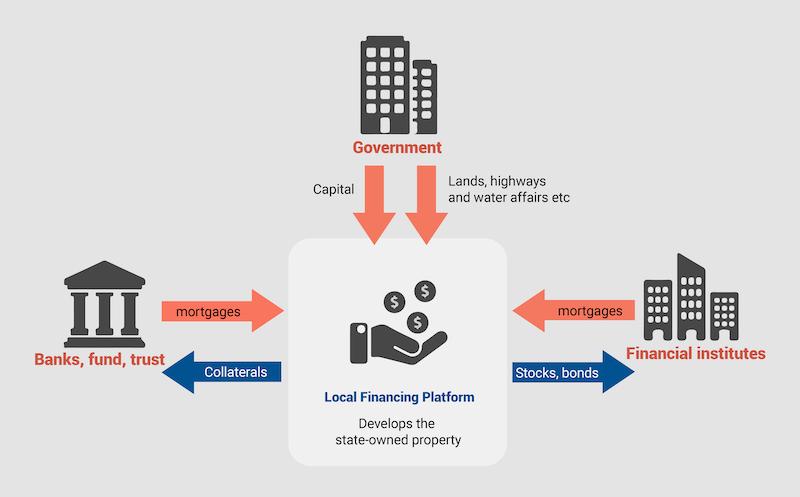

First, the government establishes a local government financing vehicle (LGFV) as a corporate entity, and into this it injects state capital from land, transport, utilities and other sources. The LGFV then mortgages these assets in order to seek capital. Once they have capital, LGFVs will use this for development, for example to build infrastructure (and sometimes vanity projects and speculative ventures), in order to achieve asset appreciation. Financial institutions can then package the debt into financial products for investors. In recent years, LGFV bonds sold to the international market as high-yielding securities have gained in popularity. In the end, the government behind the LGFV and the financial institutions share in the revenue.

However, these LGFVs do not themselves have much in terms of actual assets and income, and the financing relies solely on government power. Legally, these companies are independent legal persons, but in reality, the government appoints their heads, while the local party and government organs command the investment direction and capital flow.

With the government in charge of local affairs, financing has been easy. These platforms have also become cash machines for local governments that operate outside the financial management and budgeting system. The huge debt they rack up also becomes “implicit government debt,” meaning debt that does not appear as local government debt on the books of the local authorities. The term “implicit government debt” first appeared in a meeting of China’s elite Politburo on July 24, 2017. Experts say that, in theory, implicit debt cannot be regarded as local government debt with compliance, as they are generated through actions outside of regulations (such as mortgages or letters of commitment) or through disguised debt (the faking of government purchases and so on).

At present, there is still no unified standard for identifying implicit government debt, so even the total amount of debt remains a mystery. Estimations of various types of local debt generally come to between 30 and 50 trillion yuan, or 4.3 to 7.1 trillion US dollars.

For example, Zhang Xiaojing, deputy director of the National Institute for Finance and Development of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, estimated in 2017 that the current debt of local government financing vehicles in China stood at around 30 trillion yuan. The S&P Global rating reported in 2018 that the implicit debt of Chinese local governments can be as high as 40 trillion yuan (about 5.8 trillion US dollars), or perhaps even higher.

In May 2018, He Wei, deputy director of the NPC Financial and Economic Committee, also mentioned the number 40 trillion. Professor Bai Chong’en of Tsinghua University has estimated that the correct number is about 47 trillion. If this debt figure was to be calculated as a ratio of China’s 2017 GDP along with other known forms of debt, China’s debt-to-GDP ratio would be 72.3 percent. This is far above what some economists would consider the red line, although there have been debates about how much debt is actually too much debt.

Calculations at the local level are even more staggering. According to expert analysis in 2018, although records showed explicit local government debt-liability ratios at the provincial level in China – calculated as local government debt over local government finances – standing just above 70 percent, this rises to more than 200 percent when implicit government debt is factored in. Of the 29 Chinese provinces for which statistics were available, 21 had debt levels exceeding the International Monetary Fund warning line of 150 percent. Only Tibet and Inner Mongolia were below 100 percent, and Tianjin, the highest, is approaching 600 percent. He Wei also admitted: "Our government credit is very poor, it may even be worse than companies . . . . Many local governments can't even repay interest."

Printing Money, Leasing Land

How could the government repay huge debts and how could it continue to invest in development? Without a government bankruptcy mechanism or an open financial environment, overprinting currency has become a thirst-quenching spring. China’s money supply was 1.53 trillion yuan in 1990 and reached 85.16 trillion in 2011, increasing 59 times in 21 years. In the same period, the total amount of US money supply increased by only 1.99 times. The broad-sense money supply of RMB in 2018 reached 173.99 trillion yuan, an increase of 112 times over 38 years from 1990, according to the data of the People's Bank of China.

All of this money is issued through public investment and loans. Take, for example, the government’s “Four Trillion” investment plan, a quantitative easing and stimulus plan which was aimed at coping with the 2008 financial crisis. These funds flowed into infrastructure construction led by state-owned enterprises and governments at all levels and became an important source of income.

New residential buildings go up in Dalian, Liaoning province. Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Arana, available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.