PCR test on a car. Image generated by DALL-E AI system and recreated by Liang Shixin.

Political or Economic Calculus?

As China clings to its zero-covid approach, new investments announced by international business show how little the latter knows about the political restraints on the Chinese economy.

Quick Takes

-

Bullishness about investing in China suffers from path dependency based on the Chinese development trajectory since 1978 while overlooking the structural challenges inherent in the China Model.

-

It is a myth that the CCP bases its legitimacy on economic achievements. The zero-covid policy demonstrates when political and economic objectives collide, the former gets priority.

-

The ‘closed-loop’ production, which Western companies implement in their plants across China, is neither efficient nor rational. Above all, it harms the physical and mental health of the workers.

-

Chinese consumer market shrinks due to lack of confidence: extreme pandemic controls hit the service sector hard and have caused massive unemployment, while much of the middle class is considering emigrating abroad.

Undershooting market expectations, GDP growth in China dropped to 0.4% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2022, July figures from the National Bureau of Statistics show . Monthly figures for July also show flagging growth in the world’s second-largest economy: . On the other hand, foreign investment in China kept growing at a rapid clip in the first half of the year. Investment from Germany was up 23%, the Bundesbank stating its total level as 10 billion euros. In June, the BMW joint venture opened a new factory in Shenyang in northeast China with an investment totaling 15 billion yuan (approx. 2.2 billion euros). Shenyang is now the largest BMW Group production base worldwide. Ground was broken just days later on Audi China’s first all-electric vehicle plant in Changchun in Jilin Province, a 2.6-billion-euro investment. In July, chemicals giant BASF announced US$ 10 billion of investment in a new integrated chemical plant in Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province.

Jochen Goller, President and CEO BMW Group Region China, © BMW Brilliance Automotive Ltd.

Why would German businesses continue to ramp up investment at a time of increasing China-EU tensions? A report from the Munich-based IFO institute in August argues that German companies are running scared of the financial losses an economic decoupling from China would bring: “on the one hand, sales markets would disappear, while on the other hand, primary products and raw materials would become more expensive for German industry.” China, for German investors, is thus not just a source of cheap primary inputs to draw on but also an enormous pool of consumers. To the extent that capital seeks out profit, this is understandable; nonetheless, European bullishness about investing in China suffers from a path dependence based on the Chinese development trajectory since 1978 while simultaneously overlooking the structural challenges inherent in the China Model. The two drivers of the Chinese economy – the demographic dividend and the economic spillovers from real estate – are now at the end of their respective roads. Meanwhile, the long-term structural damage caused by the previous 4-trillion-yuan stimulus package from 2008 is plain to see: monetary overexpansion leading to overcapacity, inflation, soaring house prices, eye-watering local government debt, bank liabilities, falling productivity, low-yield investments, and critical wastage of resources. The onset of these problems tells us that China has missed its ideal window for structural reform. In 2018, long before the Covid pandemic outbreak, Professor Xiang Songzuo from the Renmin university stated that “the Chinese economy is going to be in for long-term and very difficult times”, as as he estimated the growth rate in 2018 went negative, while the speculative bubble of China is about to burst.

The COVID-19 pandemic has gradually brought systemic economic and social crises out from under the surface. There is now almost no way for the country to avoid the middle-income trap, and stubborn adherence to a dynamic zero-covid policy has only accelerated this trend. For example, battered by a city-wide lockdown, Shanghai’s economy shrank 14% in the second quarter of 2022.

Since April, Premier Li Keqiang has attempted to respond with a series of economic rescue measures, most notably the May announcement of a 12-trillion-yuan stimulus package. Despite the short-term boost this will produce, a long-term debt morass for local governments is equally sure to result, with early warnings in the shape of recent bank liquidity crises and mortgage boycotts. This essay will examine the far-reaching economic and supply-chain consequences of the zero-covid policy in China and the fallout suffered by factory workers and middle-class consumers. The goal is to display how irrational pandemic policies have distorted manufacturing and consumer demand and to expose the two levels of fallout they have caused for workers and consumers. This analysis aims to be of relevance to European policy and business decision-makers.

It’s not the Economy

The consensus among many Western China-watchers is that the Chinese Communist Party bases its legitimacy on achievements in development; that is to say, the priority is the economy: The approach taken to COVID-19 over the past two years reveals this to be a myth.

Economic work was indeed a focus of the July Politburo meeting. However, the session laid down the following conclusion: “a comprehensive, systematic, and long-term approach will be taken regarding the relationship between pandemic control and economic and social development; in particular, the approach will be a political one, with a political calculus”.

“Political calculus” (政治账) refers to weighing policies by their political impact rather than their economic outcomes. During the CCP’s time in power, the phrase ‘political calculus’ has been regarded as both a positive and a dirty word. During the Great Leap Forward (1959-1961), the establishment of the People’s Communes led to a devastating famine and tens of millions of excess deaths. In the wake of criticism from Party insiders and the Soviet Union, Mao Zedong retorted: “we cannot just go by an economic calculus instead of a political one” . The driving ideology behind policy decisions throughout the Cultural Revolution was the overwhelming importance accorded to the political calculus, while the economic one was a mere afterthought. When the Reform and Opening-Up era ushered in, the top of the party members reached an agreement. “Using a political calculus to the exclusion of the economic one” has been one of the worst mistakes of the Cultural Revolution; whereupon, the use of the phrase “political calculus” fell out of favor for a long time. In 2013, the Central Party School’s Study Times argued that Party Secretaries “are not economists or business people; they must have a political calculus, a social calculus, rather than just an economic one”. This article effectively rehabilitated “political calculus” as official jargon.

Whichever calculus the successive leaders have used, the Great Leap Forward has taught them one lesson: causing tens of millions of deaths through policy mistakes will seriously endanger your political legitimacy and leave a black mark on your legacy. By the same token, the logical assumption is that if the zero-covid policy is relaxed, it will cause the Omicron variant to spread widely, unnoticed, seriously harming hundreds of millions of the elderly population and patients with underlying diseases (as can be seen from the nearly 10,000-high death tally from the fifth wave in Hong Kong). Any leader would fear the political and historical repercussions of a result like that. This fear, together with the vested interests of the Chinese companies involved in PCR testing and vaccines, plays a crucial role in why China will not be moving off the zero-covid path in the foreseeable future – there is no alternative.

Left: Image of the Great Leap Forward from the internet (photographer unknown). Right: Large-scale nucleic acid testing in Guancheng Civic Center, Dongguan, available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

Since COVID-19 first broke out in Wuhan, Chinese government responses have centered on non-medical/pharmaceutical interventions: restricting human movement, increasing social distancing, and early discovery and quarantine of positive cases were all enshrined as wide-ranging and absolute imperatives. Chinese media defends this approach by highlighting the deficiencies in pandemic management in Western countries and high death rates.

To promote nationalist sentiment and support the Chinese vaccine industry, China refrained from granting authorization to more-effective mRNA vaccines. Over the past year or so, various coercive means have been employed to make the country take domestically produced inactivated virus vaccines such as Sinovac. China’s inoculation rates are now some of the highest in the world, but data from Hong Kong shows that two or even three shots of Sinovac provide much weaker protection against Omicron than the BioNTech / Pfizer vaccine. Consequently, faced with the faster transmission rates of the Omicron variant, shorter incubation period, and lower risks of serious disease and death, China cannot take a more flexible approach to its stringent control measures. Instead, the government, feeling obliged to plow ahead with ‘dynamic zero-covid’, targets much larger areas with rapid ‘containment’ tactics, and maximizes restrictions on the movement of people and goods.

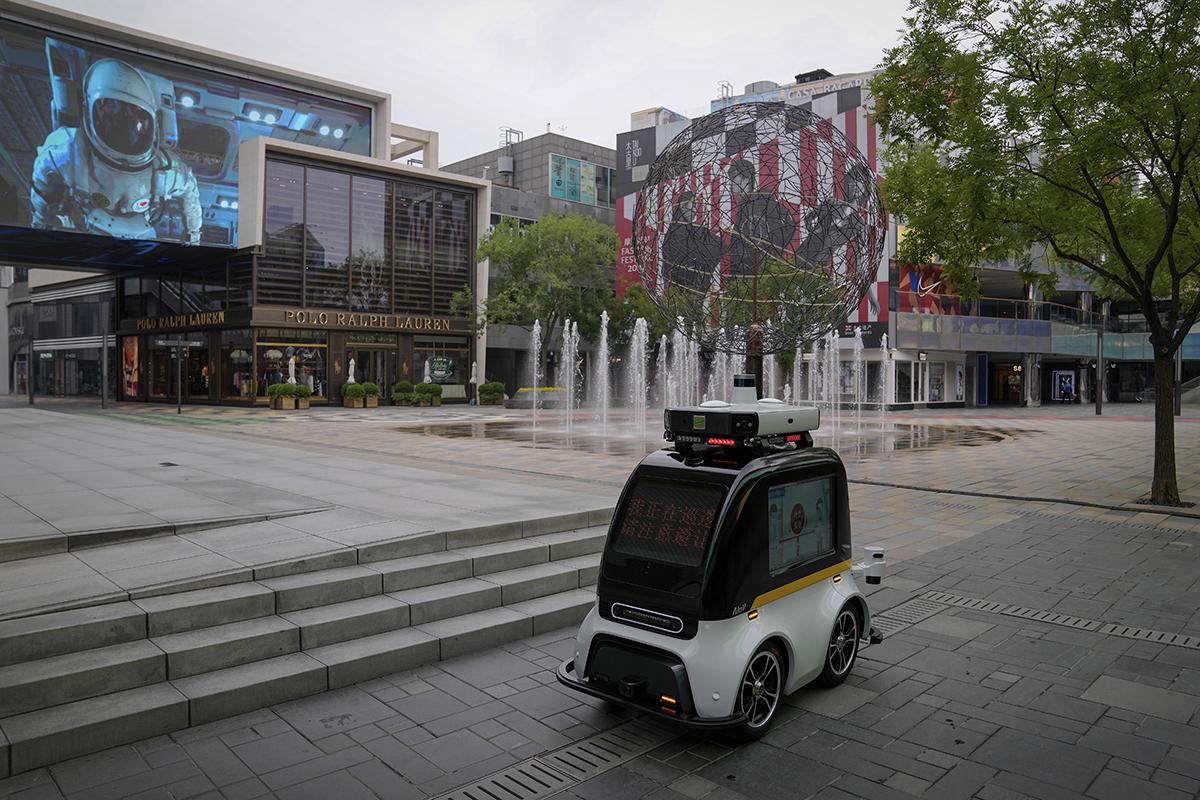

From a purely epidemiological point of view, isolation and quarantine can play a significant part in stopping the virus from spreading, but it must be taken into account that human mobility is a social and economic phenomenon. China’s campaign-style pandemic control system consists of three pillars: mass PCR testing of entire populations, ‘static management’ imposed on entire areas, and wholesale confinement of people in temporary ‘Fangcang’ hospitals. The issue is that these should be temporary measures to buy time for mass vaccination to be carried out, but there has been mission creep and they have become permanent. With the economic downturn irreversible, they are now held up as a new symbol of the ‘strengths’ of the Chinese system. Whereas, the Western response to the pandemic is interpreted as a disaster and evidence of “Western decline”. According to this logic, the economy is a price worth paying for political goals.

With the economic downturn irreversible, China’s pandemic control methods are now held up as a new symbol of the ‘strengths’ of the Chinese system in the face of apparent Western decline.

Shanghai’s 50-day lockdown in 2022 disrupted world supply chains and left Western investors concerned. But the regions all around China suffering from the same lockdown and isolation measures, some for months on end, has been internationally much less noticed. As of the 11th of September, 1276 high-risk areas have been declared nationwide, and 1442 as medium-risk ones. Being a ‘high-risk’ area means, under official rules, residents cannot leave their homes; in ‘medium-risk’ areas, residents are still confined to their residential compounds.

Take the city of Beihai, Guangxi Province. This popular southwestern coastal destination mostly depends on tourism and its fishing industry. The peak local holiday season was cut short on 12 July by an Omicron outbreak with over 700 infections in seven days. What would be considered a minuscule event in other countries was treated as a major incident in zero-covid-obsessed China. The performance of local officials is now measured by their loyalty to the zero-covid policy, so they must take any measures possible to secure their positions.

A video circulating online shows protesters in Beihai demanding the end of lockdown.

Beihai authorities sealed off all tourist areas and broke the city down into a 5240-zone grid through which “a dragnet-style virus screening [was] carried out of the city’s 1.856 million population, assisted by Big Data”. Police worked 24-hour shifts, and traffic was banned while the urban population underwent several rounds of compulsory PCR testing. In early August, a Beihai resident lodged a complaint letter with the State Council’s “Internet+ Supervision” website: “I urge you to cancel the pandemic measures and lift restrictions, we are really on the brink now … can the government not think of the ordinary people? Lots of people are left with no income now. When is this endless series of pandemic measures going to stop? Are we going to be locked down for the rest of our lives? Why are other countries all able to reopen, is it only the Chinese who are smart, and all the others are dumb?” The complaint letter quickly disappeared without trace online. The fishing season usually opens on August 16th in Beihai, but the authorities extended the catch moratorium for a month, causing angry residents to hit the streets in protest; this compelled the authorities to announce a complete relaxation of restrictions at midnight that evening.

But Beihai was the exception. It is also wishful thinking to expect China to abandon the zero-covid policy after the 20th Party Congress later this year, as that would be to ignore how central political legitimacy and place in history are to the image of a Chinese leader. Although the principle of performance legitimacy has been cemented over the past decades of Reform and Opening-up, given the material prosperity they unleashed, when political and economic objectives happen to be at odds or come into conflict, the former gets priority. The Chinese party-state can handle economic weakness, for example, by espousing the concept of a “new normal” to explain away weaker growth in recent years, but it cannot stomach the idea of a political challenge. The crackdowns on private entrepreneurs such as Jack Ma or key industries such as the tech sector provide proof of the latter.

The economic cost of zero-covid

What has the economic cost been of the political campaign against COVID? Research by Michael Song, Professor of Economics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong suggests that a two-week lockdown caused economic damage equivalent to around 32% of Hong Kong’s GDP for that month or 2.7% of GDP for that year. While a month-long lockdown would cost 4.5% of the city’s annual GDP. Relaxation of lockdowns, while allowing the economy to recover to its pre-lockdown levels, would not lead to a bounce-back effect. This research was carried out before Shenzhen and Shanghai lockdowns; if we run the calculations for the latter two conurbations, the cost of a two-week lockdown would roughly equate to 190 billion yuan (27 billion euros), a colossal sum. The brutal economic consequences of China’s zero-covid policies for the country and the world are evident with the effects of Shanghai’s two-month lockdown.

The Yangtze River Delta, a cluster of cities centering around Shanghai, is a major world auto manufacturing hub. The automotive supply chain suffered the furthest-reaching consequences since automotive supply chains are a complex and finely calibrated ecosystem where one vehicle requires more than 10,000 parts to make. Supply chains are long, highly globalized, and involve low inventories of parts, so they are highly coordinated; if any one humble part is unavailable, production grinds to a halt. Shanghai produces 11% of the cars in China. Over half the world’s major part makers have headquarters or major production clustered around Shanghai: Tier 1 part suppliers, chipmakers, Tier 2 and 3 suppliers such as producers of instrument panels, seats, and tires, and raw material suppliers such as metal and glass. There are over 1000 companies of significant size in the local auto supply chain; that number swells to over 20,000 once small and micro-enterprises are included.

Logistics is the lubricant that keeps the cogs of the automotive supply chain running. With no logistics, auto makers’ capacities would be diminished. For example, Shanghai’s neighboring provinces Zhejiang and Jiangsu imposed heavy restrictions from late March to late June: the number of available motorway tollbooths and service areas was reduced, and frequent spot-checks of haulers’ traffic permits, health QR codes, and PCR results were carried out. As a result, many trucks ceased operations or were left unable to exit the motorway. The automotive supply chain foundered due to companies being unable to get supplies in, get their products out, or pay transport costs that outstripped the relevant part manufacturing costs.

To name a few, Tesla, NIO, and SAIC-Volkswagen (Volkswagen's joint venture in Shanghai) had to announce pauses in their car output due to the Shanghai lockdown. The scale of the resulting economic damage is evident in the Tesla figures: factory idle for 24 days, 48,000 fewer cars produced, and at least 14 billion yuan in loss of revenue.

Shanghai municipal authorities tried to restart manufacturing using a ‘whitelist’ on 16 April, authorizing certain companies to reopen operations. 666 companies were whitelisted, the largest category among whom (251) was the automotive industry, over 80% of whose facilities had gone into full idling mode. One week later, a city government press conference claimed that 70% of the 666 companies listed had resumed production and that improvements had occurred in automotive company productivity and capacity utilization. This claim was bureaucratic sleight of hand; no specifics were given in terms of how many cars had rolled off the line, how many had been dispatched from the factory gates, or which cities they had been delivered to. Restarting a factory is not just a matter of flicking a switch to get back to full speed; for example, Shanghai Volkswagen had only got back up to 50% capacity utilization at its various plants by the end of May, and Bosch, the world’s largest auto part supplier had only got its various part lines back running at 30-75% of capacity by the middle of that month.

Given the continued uncertainty posed by the zero-covid policy and the possibility of different grades of the local lockdown imposed at any time, the Chinese automotive supply chain is unlikely to see manufacturing activity return to pre-pandemic levels. Ongoing challenges for the auto industry include adjusting to shifting downstream demand, getting staff back in place, and logistics bottlenecks.

Working under the New Normal

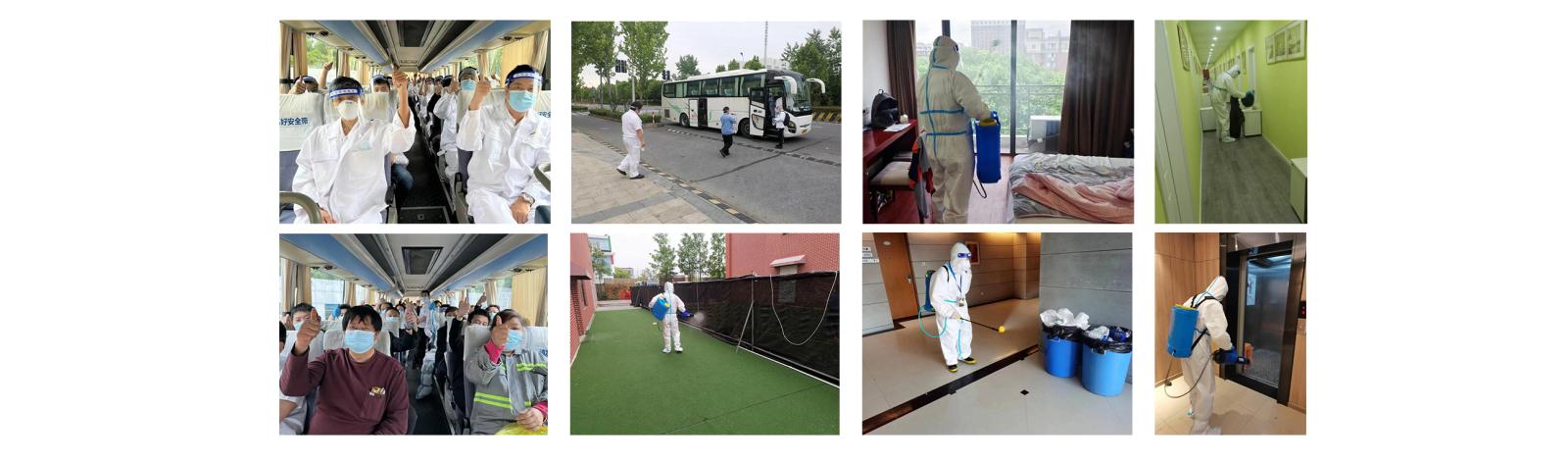

Another challenge in getting back to business is pandemic rule compliance with company staff. Shanghai Municipality announced a rule in April that companies restarting operations would have to carry out and log health checks for all their staff: antigen tests for all in the morning, PCR tests in the evening. Physical separation was required between zones, and all staff was required to stick to designated workstations and sleeping quarters, to minimize contact between staff in different zones.

This requirement proved difficult to implement. Different regulators applied different standards. Residents’ Committees (the lowest level of the governance apparatus) were sometimes unwilling to recognize documentation issued by employers attesting to the need for their workers to leave home and come in, as the Residents’ Committees were under a lot of political pressure to prioritize pandemic control. This led to situations where management staff in residential compounds refused to let residents leave, and coaches sent by the company were unable to bring their employees back in. With the considerable bureaucracy involved and general low efficiency, the actual attendance rate by workers was very low, and even those permitted to come in were not allowed back to their homes, effectively having to ‘live at the factory.’

Shanghai’s SAIC-Volkswagen started ‘closed-loop management’ (封闭管理)on March 14th, as reported by Chinese media, with over 8000 staff eating and sleeping at their workplace. Some employees suddenly received overtime notices as they approached the end of their shifts. They did not realize that the half-hour of overtime would mutate into several weeks of confinement in their factory. The company laid out camp beds, tents, and yoga mats for their staff, who were expected all to ‘sleep neatly in rows’ at night. During the lockdown, each person worked around 10-hour shifts.

Left: A sleeping area for workers in the SAIC Volkswagen plant under closed-loop management. Screenshot of WeChat public account of SAIC Trade Unions 上汽职工之家. Middle: Workers of Jabil Circuit Wuxi plant staying on the floor overnight. Right: Tents set up within the Shanghai InnoLux production site, both screenshots from TikTok.