Photo for Echowall by Liang Shixin.

Local Debts: a Top-Level Design

How China's central and local governments have jointly ushered in a debt-based economic model in the past decade.

Quick Takes:

- Local debt explosion in China results from a joint effort by central and local governments rather than a localized issue.

- China's debt-driven model has undergone three major rounds of fiscal and monetary expansion initiated by the central government: Stimulus after the 2008 Financial Crisis, monetized shanty-town resettlement in 2015, and the pandemic-induced expansion since 2020.

- In 2009, China's central bank promoted local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) for debt financing, enabling local governments to bypass legal restrictions on debt raising.

- Local governments' heavy reliance on land revenue, coupled with lax judicial supervision and rent-seeking, has led to real estate speculation and unsustainable debt growth.

- Given the central government's incompetence to regulate the finance market and reduce dependency on the real estate sector, the local debt crisis will continue to affect China's economy.

Since 2008, the Chinese central government has designed three major fiscal and monetary expansion rounds, which spawned a debt-based economic model driven by government borrowing and investment. Local government financial vehicles (LGFVs) were set up in cities nationwide to carry out financing, large-scale land sales, new zone development, and infrastructure and real estate projects. This apparent ‘economic miracle’ drew plaudits; however, due to laxity regarding fiscal discipline, bank credit, corruption, and rent-seeking, the results have also included excessive local government borrowing, meager project yields, and huge LGFV debt risks. China’s post-coronavirus recovery in the first half of 2023 has been halting, with CPI inflation plummeting to near zero, policy interest rates unchanged, real market interest rates tracking upwards, real debt service costs up, and a looming ‘debt-deflationary spiral.’ The following is the first of a two-part reflection, which will identify the factors behind the hidden local debt explosion, China’s options for responding to the debt crisis, and its far-reaching macroeconomic effects.

World-Leading: China’s Local Government Leverage Ratio

China’s government has an overall leverage ratio due to have reached around 100% by the end of 2022, lower than the US (145%) and Japan (260%). Whereas public debt in Western countries is structurally dominated by sovereign debt, Chinese government debt is mainly made up of local government debt, which amounts to 74% of GDP, the highest such level in any major economy; local government debt in the US and Germany makes up under 30%, in France and the UK below 10%.

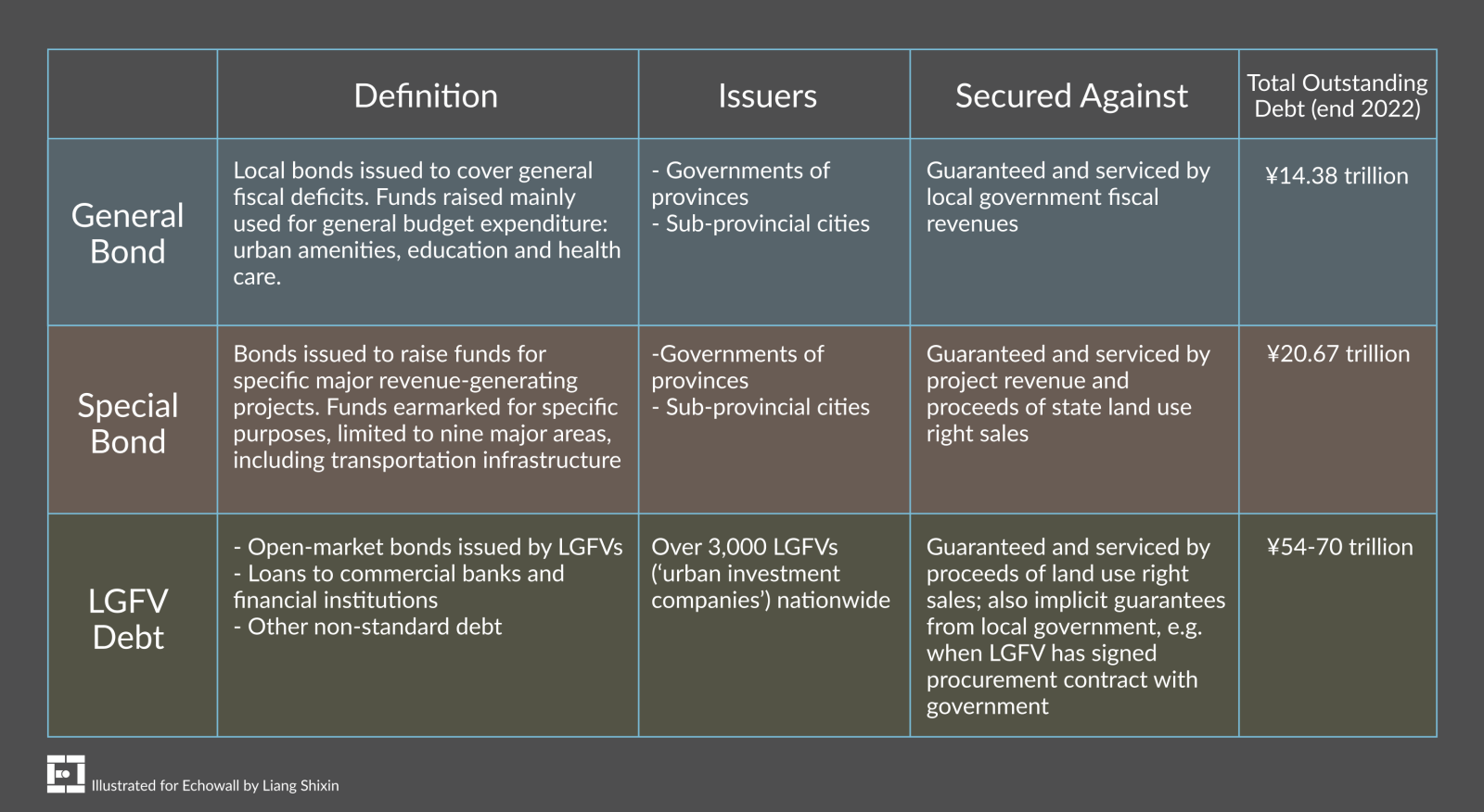

There are principally three types of Chinese local government debt: ‘General bonds’, ‘Special bonds’, and LGFV debt. ‘General bonds’ refers to bonds included in the general budget for public services. ‘Special bonds’ refers to bonds that are part of a government fund budget, which are earmarked for certain revenue-generating public amenities. General and special bonds are explicit liabilities and are mainly issued on the open market by provincial governments and those of "sub-provincial cities .” As of the end of 2022, outstanding explicit local government debt totaled ¥35 trillion, equivalent to 28.9% of GDP; general bonds made up ¥14.38 trillion, and special bonds ¥20.67 trillion.

LGFV debts, on the other hand, are a kind of implicit debt since a major share of them is not issued on the open market. They consist of bond issues by state-owned LGFVs, credit issued by banks and financial institutions, and other so-called “non-standard debt” (for example, in the shadow banking system). According to the data aggregator Wind, there were 3,027 ‘urban investment companies’ (LGFVs) nationwide as of July 24, 2023, and these had 19,633 LGFV bond issues outstanding.

Local governments use credit guarantees and implicit credit lines to arrange debt financing for LGFVs, and the latter then invest in infrastructure, develop urban land, operate real estate, and invest in for-profit projects such as tourist sites and industrial parks. Since the function of LGFVs is to finance, invest and generate revenues for local governments, LGFV debt is highly bound up with local government interests and usually recognized as (implicit) local government debt.

If we take the case of a new high-speed railway, the general central budget finances the railway itself, local special bonds raise funds for the station in the city in question, and LGFV finances highways, parks, industrial zones, wholesale markets, and condominium developments, forming an economic cluster around the new high-speed rail station.

An essential financial ‘weapon’ in local governments’ arsenals, LGFVs have contributed to local GDP and infrastructure, but their real economic benefits are the crux of much debate. Local governments and LGFVs have overinvested and taken on heavy debt over the past decade or so, and in recent years local government revenues and LGFV debt-servicing capacities have deteriorated rapidly.

LGFV debt is rather concealed: besides close to ¥14 trillion publicly issued on bond markets, significant amounts of the debt are not recorded or accounted for. According to Zhongtai Securities, total outstanding interest-bearing LGFV debt stood at ¥54 trillion by the end of 2022, equal to 44.6% of GDP. However, based on broad measures, LGFV debt may total as much as ¥70 trillion.

Let us take the example of Dushan County, Guizhou Province. The county has poor economic fundamentals: fiscal revenue of only ¥1 billion in 2018 and government debt as high as ¥40 billion. The Dushan County government borrowed and built aggressively since 2010, its projects including a megalomaniac building referred to as ‘world number one’ at the cost of ¥200 million, a 1,000-hectare university city at the cost of ¥2 billion, a ¥1.35 billion racecourse, a ¥1.52 billion ‘old town’ project, and a ¥1 billion big data center, more or less all of which ended up with construction suspended due to cash flow problems. This plunged the county's finances into a morass of debt. From 2018 onwards, Dushan County’s party secretary, county head, and many other officials were arrested for corruption.

Screenshot of a report by CCTV.com about Dushan County and the ‘world number one’ building.