Original illustration by Tse Yuet Ching for Echowall.

Putting Europe Last?

Public debate in EU member states can enhance national and EU policy-making on China, but analysis of the 2019 Dutch policy paper on China and the surrounding debate suggests lack of strategic thinking and resolve on the member-state level may undermine cohesion and policy effectiveness on the EU level.

Since the first direct contacts in the early 17th century, relations between the Netherlands and China have passed through three broad stages. During the first stage, Dutch seafarers followed in the footsteps of their European peers by submitting to a Sinocentric regional order and paying tribute to the emperor in the hope of accessing new markets and sources of supply. In the next stage, during what has come to be known as China’s “century of humiliation,” the scales tipped in the other direction, and the Dutch became active stakeholders in a similarly unequal, but this time Western-dominated, system of unilateral advantages and imperialist interventions that helped bring down the Chinese empire.

Finally, the Second World War and the Chinese Civil War that ended in the establishment of the PRC in 1949, saw the Netherlands and China striking a golden balance between the two outmoded systems, ushering in a third stage in their historical ties based on modern Westphalian principles of legal equality and sovereignty.

Johan Nieuhof, a Dutch traveler who became an authoritative Western writer on China in the 17th century after making a trip from Canton to Peking in 1655-1657. Image from Wikimedia Commons in the public domain.

This hard-won equilibrium survived the Cold War and lasted all the way through to the beginning of the 21st century. In 1950, the Netherlands was among the first Western European states to recognize the PRC government in Beijing and sever relations with the Nationalists at Taipei. This was followed in 1954 by the establishment of (semi-)diplomatic relations and, after the Dutch government had reconfirmed its One-China policy in 1972, by an upgrade to full ambassadorial ties.

Bilateral ties have developed rapidly since the 1970s, despite occasional setbacks and tensions, such as over the sale of Dutch submarines to Taiwan and Dutch criticism of China’s human rights record. In 2014, President Xi Jinping chose the Netherlands as the first stop of his European tour. During the visit, the two sides reached agreement on an Open and Pragmatic Partnership for Comprehensive Cooperation. In October the following year, King Willem Alexander of the Netherlands repaid Xi’s historic visit with a state call to China.

The Balance Shifts Again

Around this time, however, the notion started to take hold in several Western capitals that China’s growing global reach and ambition signaled a shift in the geopolitical balance that might threaten the very foundations of the post-war order. Perceptions of this kind, reinforced by broader security concerns and anxiety about the future of multilateralism, prompted calls across the EU region for a reappraisal and potential recalibration of the relationship with China. It was against this backdrop that the Dutch government published a policy paper on China in May 2019, entitled “The Netherlands and China: A New Balance.” Several media outlets and observers have since commented on the paper. However, to date, no dedicated analysis of its strategic value and potential implications, including on the EU level, has emerged. Redressing this shortfall, this article asks to what extent the recent Dutch policy proposals and surrounding discussions have the potential to further the EU-wide shared goal of securing a new balance in the relationship with China.

Recent Dutch Policy on China

This latest Dutch policy paper was preceded by several similar documents. In 2006, the foreign ministry issued a policy vision on prospective cooperation with China during the years 2006 to 2010, a period coinciding with China’s 11th Five Year Plan. The document, which appeared at a time when US officials were urging China to become a responsible stakeholder in the global system, underscored the interest of the Netherlands in a stable, responsible, and sustainable China. The government optimistically stated that it saw China principally as a country that offered opportunities, rather than threats, and that “constructive discussion” was the natural way forward in areas where mutual views might diverge. The Dutch optimism about China’s economic growth led the European think-tank ECFR in 2009 to label the Netherlands, alongside Denmark, Sweden, and the UK as, an “ideological free trader.”

A second policy document on China emerged in November 2013. Compared with the earlier one, the 2013 paper placed greater emphasis on the differences existing between the two countries and the importance for the Netherlands to encourage economic and political reform in its engagement with China. Accordingly, the paper proposed a dual approach of “investing in values” and “investing in business,” seeking to open up space for candid discussions on values and human rights, while at the same time stepping up economic diplomacy.

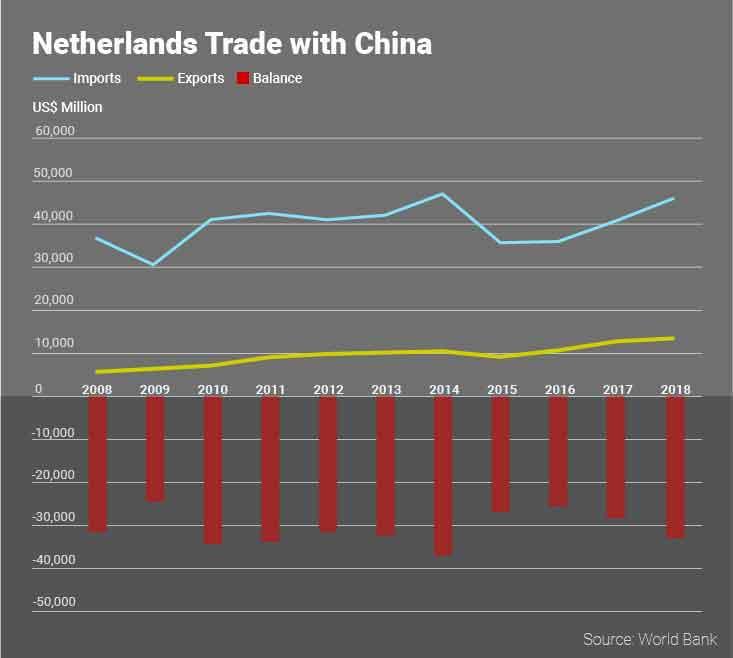

By this time, the Netherlands had been ranked for a full decade as China’s second-largest trading partner in the EU, a position it subsequently lost to Britain, but is slated to regain post-Brexit. At the same time, the Netherlands has been one of a handful of EU member states to insist on having its own human rights dialogue with China and to allocate an annual amount of around 2 million euro to human rights projects in China.

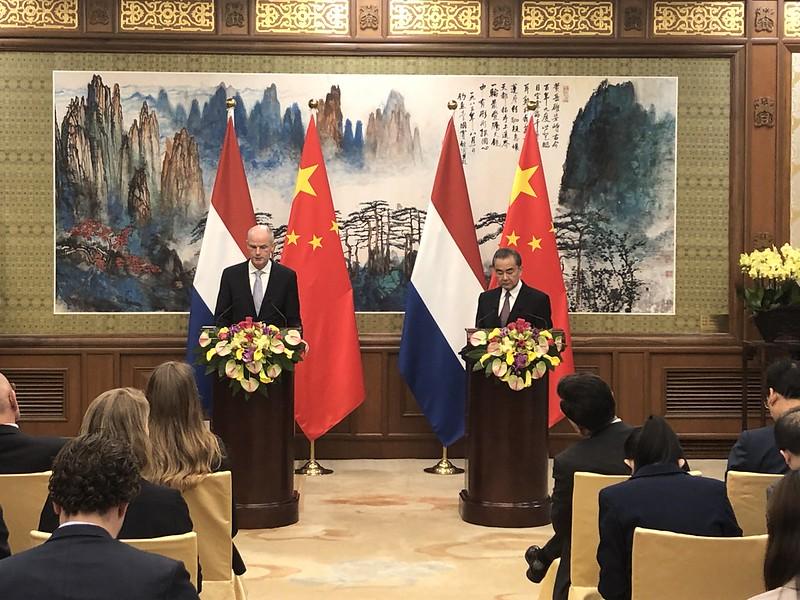

Stef Blok, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, visits China in June 2019. Here he appears at a press conference with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. Photo by Danitsja Nassy / Annemijn van den Broek, available at Flickr.com under CC license.

A recent ETNC survey classified the Netherlands – alongside Belgium, Denmark, France, and Norway – as EU member states that are “active and discreet” in their political dealings with China, thus contrasting them to the more “active and vocal” member states, such as Germany, Sweden, and the UK.

It is true that the Dutch government prefers quiet diplomacy over megaphone diplomacy in its dealings with China – precisely because it is bilaterally engaged in sensitive dialogues and project funding.

It is true that the Dutch government prefers quiet diplomacy over megaphone diplomacy in its dealings with China – precisely because it is bilaterally engaged in sensitive dialogues and project funding. But this has not prevented the Dutch from consistently supporting the EU’s more assertive recent actions vis-à-vis China. Apart from endorsing multiple public statements condemning China’s human rights violations, the Netherlands also joined a concerted EU move to criticize China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Though the Netherlands has signed a memorandum of understanding with China on promoting commercial cooperation in third-party markets, it has steered clear from embracing the BRI in the way that other member states – such as Italy, Greece and Poland – have recently done.

Securing a New Balance

Contrary to similar China papers that have recently appeared in some other EU countries, the new Dutch policy document was not a response to a particular incident or acute problem in the relationship with China. The idea of a new strategy came up during a May 2018 parliamentary session on the integration of national security and foreign policy strategies into a comprehensive international strategy. It was a representative of the Liberal party, generally viewed as pragmatic and pro-international business, who led the push for a new government strategy to deal with the challenges arising from China’s growing global influence. Foreign minister Stef Blok, also a Liberal, expressed reluctance at the idea of producing single-country papers but, faced with a joint motion sponsored by the four coalition partners, ultimately had little choice but to comply.

Five Recommendations from the Dutch Advisory Council of International Affairs (AIV) Report (2019) for Acting More Strategically Toward China:

1. Develop forums within the EU for the assessment of economic, value-related and security interests that China’s rise demands, in the appropriate locations. If this is not successful, take the initiative as a last resort to set up a strategic forum with like-minded member states outside the framework of the EU.

2. Advocate an update of the EU China strategy (2016) that expresses the wishes and demands of the member states in strategic terms of “red lines” and potential forms of leverage. Also, advocate the establishment of a knowledge network on China within the new European Commission.

3. Acknowledge that economic and technological “decoupling” of the three great trading blocs (the US, Europe and China) for specific products and for security policy reasons can be advocated, but also entails strategic risks, given that economic interdependence can have a mitigating impact on global conflicts.

4. Participate in initiatives taken by large EU member states for united action in respect of China and/or encourage EU representatives to participate in such initiatives.

5. Increase Europe’s potential leverage with respect to China (market access, technology, legitimacy, and political and economic influence), starting with what the Netherlands itself can do by, for example, investing more in technology.

A period of intensive consultations and interdepartmental discussions followed, involving at least eight ministries and several specialized agencies. According to Dutch media reports, there were major divergences between the various departments and cabinet members on key principles of engagement, with the intelligence and security agencies warning against overdependency and related security risks and the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate (and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) favoring a more open and constructive line. As stated in the policy paper, over a hundred outside experts and societal stakeholders were consulted. Nonetheless, at a high-level expert meeting just three months before the paper’s planned release date, it found itself on the defense against concerns by Dutch business representatives that the consultation process was not being conducted in an inclusive and transparent manner.

The foreign ministry officially released the paper on May 15, 2019, following a two-month delay. By this time, the status of the document had been relegated to “policy paper” from the original “strategy.” More importantly, in releasing the paper, the Dutch cabinet had apparently decided to forgo the findings of the Advisory Council of International Affairs (AIV), which it had commissioned in the fall of the previous year to give advice on the effectiveness of the EU’s China strategy and implications for Dutch policy. The AIV issued its thoughtful and nuanced advisory report in June 2019, less than six weeks after the government paper was released. In October 2019, the foreign ministry issued an official English translation of the policy paper, in which it mentions that the AIV report had in the meantime been published, but without commenting on its findings.

The first part of the policy paper contains a general introduction setting its overall tone. It describes in candid terms how ongoing global trends and shifts, and China’s rising influence in particular, have altered the geopolitical, security, and economic outlook of the Netherlands since 2013 and hence necessitate a strategic reorientation. Similar to the EU-China Strategic Outlook, published two months earlier by the European Commission and the EU High Representative, the Dutch paper notes that while China continues to offer “substantial opportunities,” it at the same time represents a development model that clashes systemically with Western values. It concludes in unmistakable terms that “the question is no longer how the Netherlands can benefit from China’s development and how we can further integrate China into the existing international order; now it is much more what China’s rise means for our own place in Europe and in the world.”

In essence, the paper advocates a shift from a policy focusing uncritically on free trade and openness to a more “realistic” approach capable of protecting core national values from potential threats. This passage reflects clearly the ambition of the Dutch government to recalibrate the relationship:

Opportunities should be seized wherever possible, but there should also be greater awareness of issues of security (including economic security), cyber espionage and undesirable influence. The government stands firmly for protection of the rule of law, security and the open economy and society in the Netherlands. It will act if the openness of the Dutch economy and society is threatened or undermined. Our openness means that we have to carefully consider whether the benefits of taking advantage of opportunities outweigh the need to protect our security, our earnings potential and values such as the rule of law and human rights. In this policy document, the government outlines the new balance it envisages in its relations with China.

Two-pronged Diplomacy

The second section, comprising the bulk of the document, sets out the Dutch government’s policy aims and the proposed strategies to achieve these aims. It does so around five main themes: (1) Sustainable Trade and Investment; (2) Peace, Security and Stability; (3) Values, Human Rights, and the International Legal Order; (4) Climate; and (5) Development Cooperation. Moreover, it distinguishes four forms of cooperation on four different institutional levels: (1) the multilateral system; (2) European cooperation; (3) national-level “intra-Kingdom” cooperation (i.e. between the Netherlands and other constituent units including Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Saba, St. Eustatius, and St. Maarten); and (4) Dutch subnational institutions and societal actors.

The paper’s approach to each of these five themes and the four forms of cooperation essentially reflects its central motto of “open where possible, protective where necessary.” The consistent aim is to maximize and take advantage of shared interests, while allowing for “ideological differences” as long as these do not threaten Dutch interests.

Five Recommendations from the Dutch Advisory Council of International Affairs (AIV) Report (2019) for Overcoming Lack of EU Consensus on China:

1. Upgrade the EU from observer to member of the 17+1 platform comprising China and a group of Central, Eastern and Southeastern EU member states, to enable the interests of the EU and of absent member states to be better promoted.

2. Be sparing with calls for and the use of majority decision-making on sensitive issues. The political costs of outvoting member states are often high. In areas where there are as yet no provisions for majority decision-making, it is not yet politically feasible to expand the options for using it through regular or ‘light’ treaty changes. There are other ways to strengthen European unity.

3. Take initiatives to achieve informal coordination on salient issues like the MoUs relating to the Belt and Road Initiative or export controls (e.g. arms exports), modeled on the recently introduced screening of foreign investments.

4. Consider substantive trade-offs or making counteroffers to encourage member states or neighboring countries to support strategically important common positions.

5. Call on member states that are obstructionist in the field of foreign policy to make use of the option of ‘constructive abstention’ rather than their veto; consider as a last resort – besides specific actions with groups of like-minded states – issuing human rights statements on an "all-except-one" basis, so that the EU can still bring its political weight to bear.

As to the means, the policy suggests a combination of “offensive” measures, typically through multilateral structures, and “defensive” measures, aimed at protecting and enhancing national resources and capacities. In trade, for example, this means that the Netherlands intends to step up international pressure on China “to tackle unfair practices” through the WTO and the EU, while at the same time updating and expanding trade defense instruments (such as investment screening) and strengthening existing measures protecting Dutch businesses and technology.

The paper sets out a similar two-pronged approach for protecting values and human rights. On the one hand, the Dutch government vows to “raise the situation in China where appropriate, preferably at the EU level but also bilaterally and at the UN, both publicly and through quiet diplomacy”; on the other, it aspires to “raise awareness about differences in values between the Netherlands and China and about Chinese motives, actions and aims in this regard” so as to “enhance the resilience” of Dutch nationals and communities against encroachments on Dutch norms and values.

The government’s plan to combat climate change and promote sustainable development in developing countries likewise rests on a two-pronged strategy of encouraging change in China, especially through multilateral diplomacy, while addressing risks and raising levels of awareness in the Netherlands and relevant third countries.

The paper highlights the importance of multilateralism both as an end in itself and as a means for engaging with Beijing. Noting the paramount importance of the EU for the Netherlands “in today’s multipolar world,” the paper frames Dutch policy on China as complementary to and falling under the “umbrella” of the EU’s China policy, with the EU as the “primary channel” for its relations with China.

Because an effective EU policy, in turn, requires cohesion among the member states, the Dutch government intends to make “greater use” of its bilateral contacts to persuade “those member states that block decision-making on China” to come back into the fold. At the same time, the paper warns, if joint action fails on important points, the Netherlands will not hesitate to establish “leading groups” of “like-minded” member states to take appropriate steps. The government also considers cooperation with like-minded partners outside of the EU to be crucial.

As this brief run-through makes clear, the paper contains few concrete innovations, new commitments, or hard choices. In typical Dutch fashion, it reflects an impossible attempt to reconcile the diverging views existing in the ministries of economic affairs, justice and security, education, and foreign affairs into a single, strategic vision. Goals and plans are expressed in broad terms and paved with references to existing policy documents and frameworks in the various issue areas.

The one concrete action envisaged in the paper is the creation of a national coordination and information-sharing platform on China, though even this proposal is couched in vague and passive terms. During the parliamentary discussions, however, it became clear that the cabinet had reserved 2.4 million euro for the establishment of a knowledge network bringing together China experts from various disciplines to promote public knowledge on China and advise central and local governments as well as societal stakeholders on China-related issues and strategies. Preparation for the network is ongoing, though progress has been slow, and its contours remain unclear.

The one concrete action envisaged in the paper is the creation of a national coordination and information-sharing platform on China, though even this proposal is couched in vague and passive terms.

A Strategic Deficit

The policy paper has not been well received by the Dutch public. The general response among most observers was that the government offered a thoughtful analysis of the changing geopolitical landscape and related policy concerns, but failed to follow this up with political decisions and avoided strategic choices.

Coverage of the policy paper in the Netherlands’ De Volkskrant newspaper calls it a “nothing note.”

Dutch media slammed the paper as a “rich information brochure” lacking any sense of urgency and concrete measures, while parliamentarians described it as a “nothing-note.” Amnesty International deplored the use of empty phrases in the paper, while criticizing the government for emulating official Chinese discourse that equates universal human rights with (discretionary) values. While most observers expressed disappointment of the lack of firm language, others called for more sensibility, self-reflection, and nuance in the debate, warning that “China-bashing” should be avoided.

The Dutch lower house debated the paper in September 2019 with the minister of foreign affairs and the minister of foreign trade and development cooperation. Members of the two relevant parliamentary committees, having previously consulted various representatives of civil society, adopted multiple motions during the four-hour debate. The most remarkable demand was that the government completely rewrite the chapter on “values,” as the text dealing with human rights was considered inadequate in light of the alarming recent developments in Xinjiang and more broadly in China. Parliamentarians from almost all political parties insisted that the Netherlands should lead the international community on this issue by approaching human rights more strategically (through linkage with trade, for example), prioritizing freedom of religion (for example, for Uyghurs and Christians), and addressing severe human rights violations more frequently and vocally.

Except for calls to impose regulatory restrictions on the export of surveillance technology and to deny trade credit insurance provisions to businesses potentially involved in human rights violations, the debate produced few concrete suggestions for innovating or improving present strategies of promoting human rights in China.

Additional motions adopted during the session demanded that the government take active steps, both bilaterally and multilaterally, to promote reciprocal and fair trade with China, undo possible benefits arising from China’s developing-country status in the WTO and other international organizations, and enable the meaningful participation of Taiwan in international organizations and discussion of global issues. In the months following the debate, the foreign ministry sent several letters to the lower house addressing some of these concerns and clarifying the official position, but offering little new in the way of policy innovations.

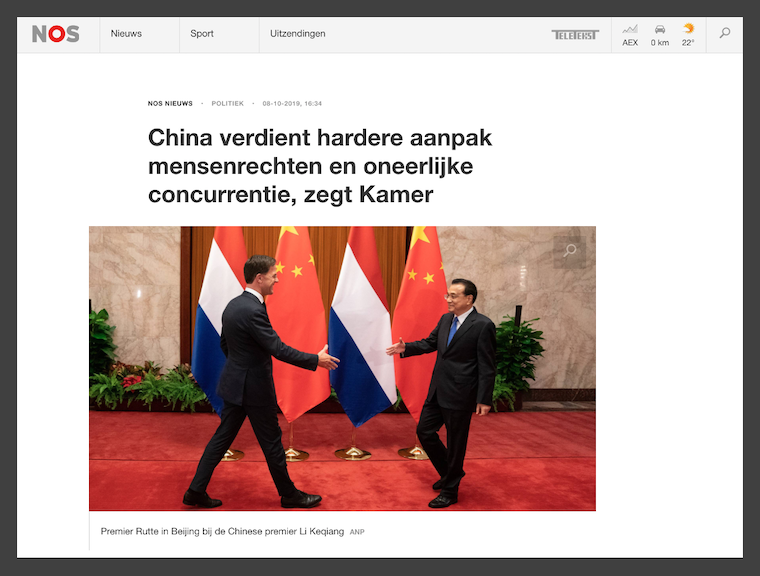

An online article from the national broadcaster NOS reads: “China deserved a tougher response on human rights and unfair competition, says Chamber.”