Image by “4X4 Blazer 1776” available at Flickr.com under CC license.

Getting Civic About Technology

While data protection is an essential priority in applying technological tools to the fight against the COVID-19 epidemic, experiences in Taiwan also provide an example to Europe in showcasing the importance of civic involvement in tech solutions.

On June 16, as Germany released its coronavirus tracking app, my Instagram feed was suddenly inundated with “slacktivist” calls along two very different agendas. Some urged people to download the “Corona-Warn-App,” doing their part to fight the spread of the epidemic. Others advocated avoiding the app altogether out of fears over data protection and questions about its effectiveness.

Germany’s coronavirus tracking app was released by the Federal Government less than two months after its April 1 announcement that it was working on a human-to-human tracing app while complying with European-level privacy regulations. The plans were met with a wave of discussion and controversy, most of which I was unaware of at the time, having recently returned to Germany from a stint doing fieldwork in Taiwan. My own experience with the app was brief and anti-climactic. I followed the link and installed it on my phone only to find that my device did not support it.

This in fact was not my first encounter with a technological solution applied during the COVID-19 outbreak. When lockdown measures took effect in Germany and elsewhere in the entire European Union in March 2020, I was already in Taiwan. My experiences as a foreigner in both places gave me a rather distinctive perspective on two significantly different approaches to the crisis.

Taiwan Responds

Despite Taiwan’s regional proximity to the center of the outbreak in Wuhan, the government in Taipei managed to successfully prevent the community spread of the virus for three months after the initial outbreak. In March 2020, as most of the world’s population found themselves in full lockdown, Taiwan remained one of the few regions in the world to implement no restrictions on movement. While there were social distancing restrictions and borders were closed to non-residents, institutions were never on lockdown and schools remained open. Taiwan’s efforts in containing the virus were widely praised in the western media, most reports highlighting early prevention measures and Taiwan’s exemplary performance in the fight against the epidemic, informed by its experiences during the 2003 SARS epidemic. One key aspect of Taiwan's success was its use of technological solutions for the quick detection of sources of infection.

Shortly after the outbreak of COVID-19, the academic journal Science published the article suggesting that social distancing, digital contact tracing and quarantine were the best “tools” available – in the absence of treatment – to stop the spread of COVID-19. Following the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, many governments worldwide turned to artificial intelligence (AI) and big data technologies to combat the spread of the virus. The response, however, was far from consistent, with different countries and regions applying different measures in different times.

One of the first localized outbreaks of COVID-19 occurring outside the Chinese province of Hubei and its capital, Wuhan, was a February outbreak onboard the British-registered cruise ship Diamond Princess, which carried 2,666 guests and 1,045 crew. On January 31, the ship docked in the port of Keelung in northern Taiwan, its passengers circulating freely in the area, including in the capital city of Taipei. The next day, Princess Cruises, the company operating the ship, confirmed that a guest from Hong Kong had tested positive for the novel coronavirus.

Shoppers wander through Taipei’s popular Ximending shopping district in 2017. Image by “A Canvas of Light” available at Flickr.com under CC license.

A few days later, on February 6, Princess Cruises confirmed there had been an outbreak onboard the Diamond Princess, with 41 people so far testing positive for the virus. This announcement triggered a quick response from Taiwan, its Centers for Disease Control (CDC) responding by forming a special unit that undertook a preliminary investigation into the ship's docking history as well as the travel routes of disembarked. The unit compiled an extensive list of locations that were visited, or might have been visited, by Diamond Princess passengers, including tourist hot spots such as the Taipei 101 skyscraper, the towns of Jiufen and Shifen in New Taipei City, and the Ximending shopping district in Taipei.

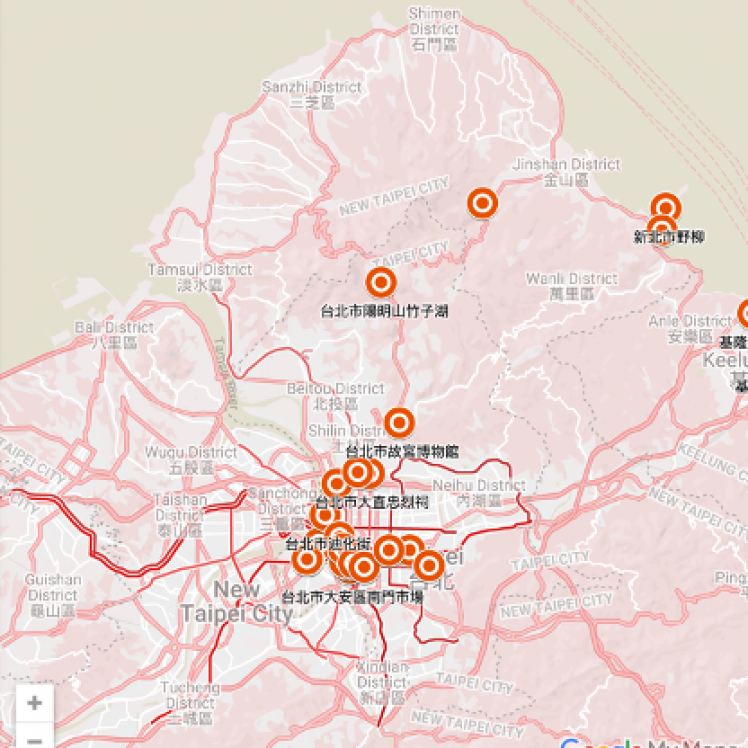

On February 7, the CDC published an online map through Google Maps of all of the potential contact points and used the country’s Public Warning System (PWS) to notify all people who might have visited those places on January 31. In order to access the necessary data to warn the population, a request was submitted to mobile network operators for a list of telephone numbers that had connected to GSM transmitters located near the places where cruise ship passengers were thought to have travelled. All mobile phone users who had been in the vicinity of potential points of contact received SMS messages informing them that they might have been exposed to people infected with the virus, and asking them to take the necessary precautions.

Screenshot of the map from Taiwan’s CDC plotting locations visited by Diamond Princess passengers.

Taiwan took the initial steps to develop the Cell Broadcast Service, or CBS, a component of the Public Warning System, shortly after the Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami occurred in Japan in 2011. The earthquake in Tohoku region, located in the northeast of Japan’s main island of Honshu, bordering the Sea of Japan, caused nearly 16,000 deaths and displaced nearly 340,000 people. Those numbers might have been higher if it had not been for a text message people in the region received within 30 seconds of the first tremors. Although the system could not save many of those in the epicenter of the earthquake, it gave thousands of people a chance to prepare for what was to come.

The experiences of the Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami prompted Taiwan, which like Japan is located in an area of high seismic activity, to develop its PWS system in 2013. The system did not become operational until 2016, rather late compared to similar systems in other countries, but since then it has been used regularly to notify citizens about various threats. During the epidemic this year, the system was used twice on a large scale.

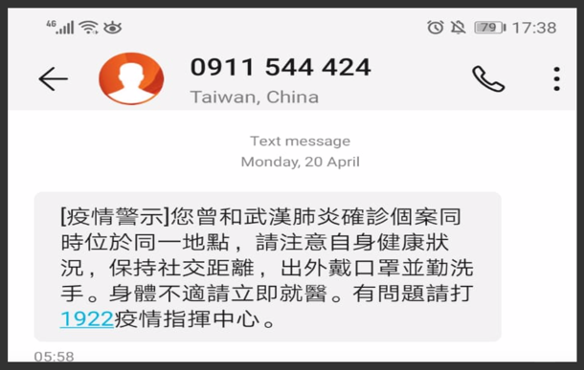

The second time the system was used, I was among the receivers of the warning message. On April 20, the morning I returned to the capital Taipei from the city of Kaohsiung in southern Taiwan, I received the following message:

[Outbreak Alert] You have been in the same location as a confirmed case of COVID-19 please conduct self-health management, keep social distance, wear a mask when you go out and wash your hands regularly. If you are not feeling well, please seek medical attention immediately. In case of any questions call the 1922 Epidemic Command Center.

I have contacted everyone I met with during my stay in Kaohsiung and learned that two of my friends received the same message. All of us were among the roughly 200,000 people identified as having been at the same location as 24 Taiwanese sailors who later tested positive for COVID-19. The sailors of the ROC Navy's Friendship fleet had returned to Taiwan from Palau on April 9, but due to separate rules on quarantine imposed for military personnel dispersed around Taiwan before they had undergone the standard 14-day of quarantine. By April 20, some of the sailors had already begun showing symptoms of infection.

Screenshot of message received by the author in Taipei in April 2020 warning of possible exposure to known COVID-19 cases. NOTE: The Chinese-language message here refers to COVID-19 as “Wuhan pneumonia.”

Shortly after sending the message, Taiwan’s CDC released a map with 90 locations visited by infected sailors from April 15 to April 18. Neither the map nor the text message contained any private data. The use of these two separate systems offered the public an opportunity to cross-check the information. But the solution was far from perfect. The text message was circulated only in Chinese, for example, and could easily be misread as spam by anyone not proficient in the language. Taiwan hosts a sizeable population of non-Chinese speaking residents, including migrant workers from Southeast Asia, who might have overlooked the warning. Nevertheless, access to other online tools and information was provided in various languages. More importantly, Taiwan’s solutions allowed access to information across various platforms and did not necessarily require possession of a smartphone.

Grassroot Efforts

The question of accessibility is at the core of discussions in Taiwan about the use of civic technology, which refers to a set of practices, mainly involving information technology, that focusses on citizens and seeks to streamline their interaction with governments. In its emphasis on citizen empowerment and public engagement, it is distinct from such initiatives as smart cities and e-governance, which tend to emphasize government agency. The origins of the civic technology movement in Taiwan can be traced back to 2012, when the Executive Yuan issued its new “Economic Power-up Plan,” a massive economic stimulus program that was criticized by many Taiwanese for lacking transparency.

Responding to the controversies surrounding the “Economic Power-up Plan,” a number of Taiwanese open source software developers, including Chia-Liang Kao and Audrey Tang, launched the g0v project, an open source and open government collaboration platform. Its goal was to rethink the role of government, starting from “zero", promoting the transparency of government information and information platforms and creating tools for citizens to participate in society.

The origins of the civic technology movement in Taiwan can be traced back to 2012.

One of the first projects implemented by g0v was the establishment of shadow government websites, which meant essentially taking the initiative at the grassroots to fix the problem of shoddy or confusing websites that made it difficult for citizens to understand the mechanisms of government. As the g0v website explains the movement:

Based on the spirit of open source, g0v cares about freedom of speech and open data, writing code to provide citizens the easy-to-use information service. The transparency of information can help citizens to have a better understanding on how the government works, to understand the issues faster and to avoid media monopoly, so they can monitor the government more efficiently, and become involved in actions and finally deepen the quality of democracy.

The simplicity and user-friendliness of the tools published by the g0v project eventually paved the way for the user experience engineered into the tools implemented by the Taiwanese government during the COVID-19 outbreak.

For two years, g0v was a standalone citizen project, without any ties to the government. That changed with the 2014 Sunflower Movement. In March and April of that year, more than 300 students, scholars and other activists occupied the Legislative Yuan after Taiwan’s ruling KMT party attempted to force through a controversial trade agreement with China called the “Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement,” or CSSTA, bypassing a detailed review that had previously been agreed with the opposition Democratic Progressive Party. The activists occupied the parliament for 23 days, drawing the attention of the entire region and encouraging more than half a million people to take the streets to join the protest.

One aspect contributing to the public response was the massive social media presence of activists occupying the parliament. They were in constant contact with the outside world. Chia-Liang Kao and Audrey Tang of g0v established ad hoc wireless network for all the participants that enabled a seamless communication channel between the protesters and public. g0v activists were also responsible for setting up an ongoing live broadcast from inside the parliament, which was streamed live on social media and on the shadow government website g0v.tw. With the help of over 1,500 volunteers, all of the speeches made by those inside the parliament were transcribed and published online.

A pair of flip flops, used to stead an iPad used to livestream protest events from within Taiwan’s parliament, became symbolic of the movement’s digital spirit. Image from Media Watch, available in the public domain.

Through this digital information strategy, the activists deprived the government of its monopoly on the monitoring and surveillance of the protest movement, ensuring that any use of police violence or attempts to reframe the intentions of the protesters would not be possible. g0v project activists became recognizable public figures during the movement, and their engagement eventually provided them with a lasting foothold within the government when it came to digital and information policy. In October 2016, Audrey Tang was appointed Digital Minister of Taiwan, in charge of open government, social innovation, and youth engagement.

Since taking up her post, Tang has established a variety of projects, including the Presidential Hackathon and Taiwan's Open Government Data Platform, both facilitating the exchange of information between the government and citizens. She prompted the establishment of the Digital Nation and Innovative Economic Development Program (also known as "DIGI+") in 2017, which provides an administrative blueprint for digital development and innovation. The program is intended to “enhance digital infrastructure, re-construct a service-based digital government, and support the development of a fair and active internet society with equal digital rights by 2025.”

The interplay during the Sunflower Movement between the government and the g0v project ensured long-term stability and support for the efforts of civic hackers in Taiwan, laying down the foundation for a coordinated response at the beginning of the COVID-19 epidemic. The role of watchdog, which these digital activists took on during the Sunflower Movement, also afforded them a great deal of public trust. Their involvement in the fight against the pandemic was seen by many as a guarantee that the rights of citizens would not be violated as technological solutions were implemented.

Ongoing Civic-Government Interaction

Despite the fact that people associated with the g0v project are now involved in the current government, the project remains an independent initiative with a strong monitoring role. The responsibility of Digital Minister is to liaise between socially engaged hackers and the administration. The apps used to provide various government-related services are constantly updated, and the majority of those contributing to this process come from outside the government. The variety of available tools range from visualizations of the government budget and data monitoring of nuclear power stations, to the mask distribution system introduced during the COVID-19 outbreak.

The need for a rational and efficient approach to supplies in epidemic response was brought home for Taiwan during the 2003 SARS epidemic, which quickly led to panic buying and hoarding of essential health equipment and supplies. The demand for face masks surged, leading to shortages, and the problem was compounded by the hoarding of supplies by certain retailers and individuals, who were hoping to profit as prices rose. The lack of available masks resulted not only in the increased spread of the virus but also in widespread public discontent with the government’s inadequate response.

The need for a rational and efficient approach to supplies in epidemic response was brought home for Taiwan during the 2003 SARS epidemic.

The experiences of 2003 were the main reason behind Taiwan’s implementation of a mask export and hoarding ban in January 2020. The government in Taipei announced that from February 6 masks would only be sold through designated pharmacies. The rationing system was implemented by the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) through its PharmaCloud System, a cloud-based health information network for medical professionals implemented in 2013, used to store medical records and allowing health care institutions, including pharmacies, smooth access to them. Under this year’s PharmaCloud System-based rationing procedures, customers would be able to purchase masks on Sundays at designated drugstores when showing their National Health Insurance (NHI) cards. For all other days of the week, sales were restricted by a staggered system on the basis of the last digit of a customer’s health insurance number.

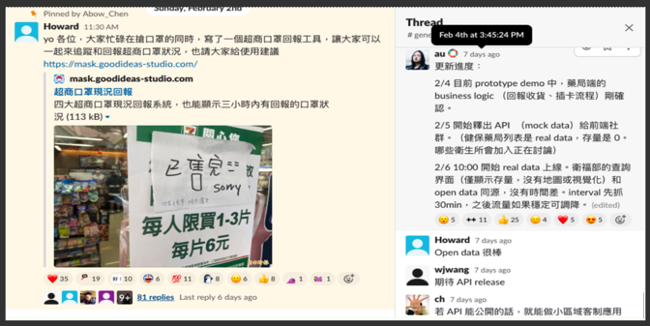

As the government’s rationing program took effect, Howard Wu, an engineer and civil hacker from the city of Tainan in southwest Taiwan, developed a relevant API (application programming interface) aimed to provide information on mask stocks in convenience stores, solely on the basis of information shared voluntarily by the public. Wu shared his project on the PTT Bulletin Board System, an online open forum community in Taiwan, where it gained public attention and caught the eye of Audrey Tang. Minister Tang decided to encourage the streamlining of Wu’s tool by publicly releasing NHI data on pharmacy locations and mask supplies to the public. This allowed Wu to update his API, providing real-time reporting of mask accessibility. The information release also allowed to the emergence of more than 130 other applications, including maps, voice assistants, and LINE chatbots.

Screenshot of the discussion between Howard Wu and Audrey Tang on the PTT Bulletin Board.