A female graduate throws her academic cap at the Asia University, Taiwan. Image by JodyHongFilms, available under Unsplash CC license.

Do China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan Mirror the Global "Liberal Women, Conservative Men" Divide?

Initium Media conducted data analysis to answer this question. Spoiler alert: yes.

“A new global gender divide is emerging,” claims a Financial Times piece in January 2024, pointing to stats illustrating a yawning political and ideological chasm between 18-29-year-old men and women in numerous countries. Young women are more likely to be liberals, while their male counterparts are increasingly conservative. Although young UK residents generally skew liberal, for example, there has been a rapidly increasing gender polarization in the last ten years: young women are now 25 percentage points more progressive on immigration and racial justice than young men. The same disparity has reached 40 percentage points in the US and 30 in Germany. The most shocking polarization is now to be found in South Korea, whose young males have ‘turned to the right’ at dizzying speeds, reaching a disparity of 55 percentage points with their female peers over about a decade.

If the FT’s survey was repeated next door to South Korea, would Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan portray a similar male-female divide on ‘gender issues’ appearing over the same timeframe? Initium Media looked in detail at Wave 7 of the World Values Survey (for which surveys were carried out in 2018 in Hong Kong and mainland China and 2019 in Taiwan) to identify trends when it comes to gender issues. We selected three of the survey’s questions: to what extent do you agree that “on the whole, men make better political leaders than women do,” “when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women,” and “[divorce, in various situations] can always be justified, never be justified, or something in between”? The results show us how men and women differ in gender-related values in each place.

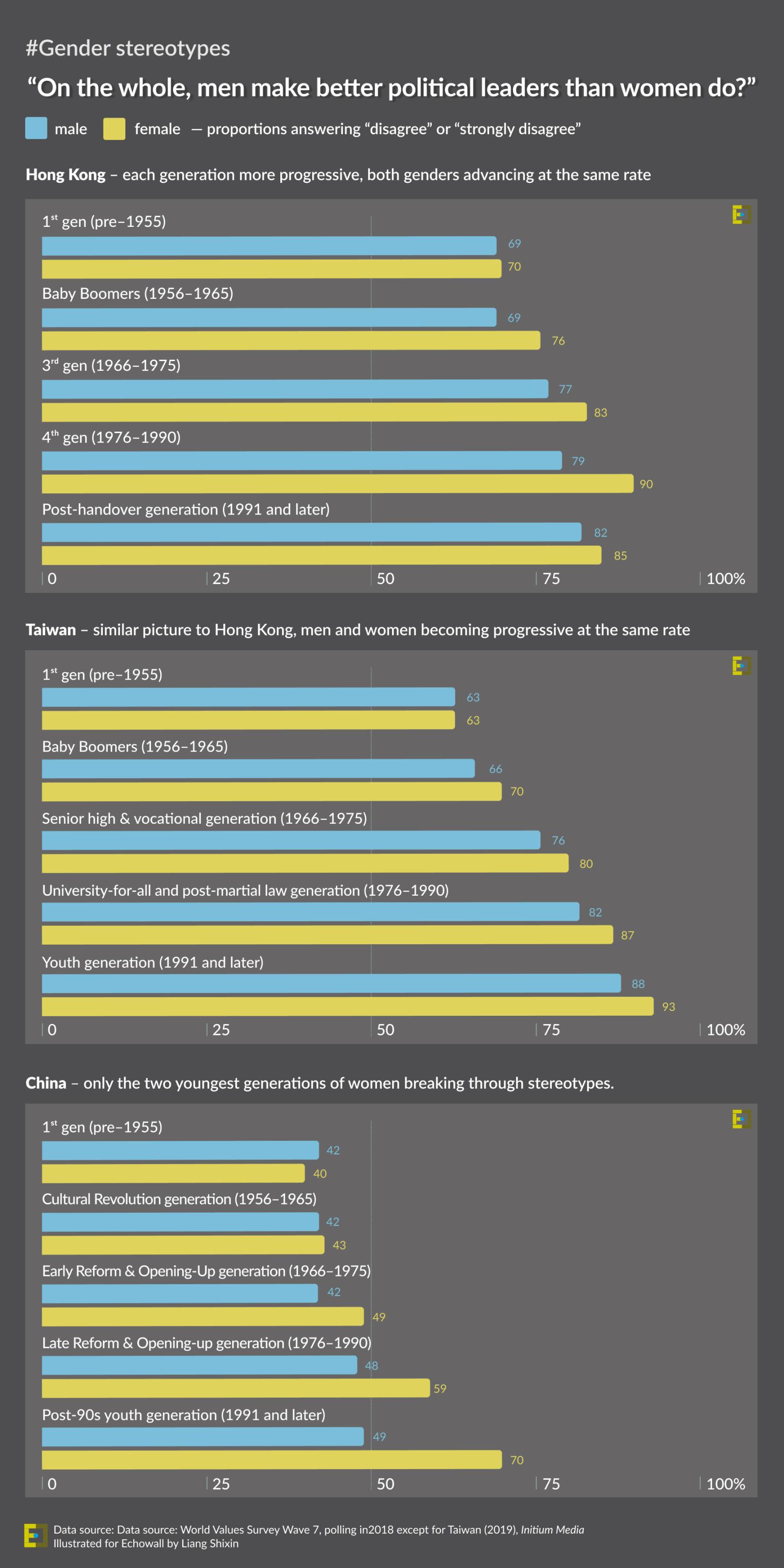

1: Do mainland Chinese, Hong Kong, and Taiwan people agree that “men make better political leaders”?

This question is relevant not just to ideas of political leadership as such but also to gender stereotypes such as women being naturally more emotional, having ‘female docility’ rather than firmness, lacking what it takes to lead and govern, and generally not being cut out to fill senior political posts. If we assume that those answering “disagree” and “strongly disagree” are more pro-equality, the results are telling; Taiwan and Hong Kong are similar, with no clear gap on this score in any generation, but mainland China is an outlier, with young women far more progressive on this question.

It was already a social consensus in Taiwan and Hong Kong in 2018/19 that ‘women are also suited to being political leaders’; even amongst the post-war Baby Boomer generation (born in 1956-1965) who are now in their sixties, only a 20% minority still clings to the old prejudices. Gender stereotypes are retreating across the board.

Looking at the picture intergenerationally, the prevalent story in Hong Kong and Taiwan is that men and women are becoming modern at a similar pace, neither outstripping the other. Thus, no generation shows a significant gender disparity (NB: in the youngest two generations in Hong Kong, women’s support for equality appears to decline, but this is not statistically significant, and support is broadly high in both generations, running at around 90%).

Things are very different when it comes to China. Traditional gender beliefs remain strong among male respondents, with not that much variation between younger generations and their grandparents – 40-50% believe women are not suited to be political leaders. Worth noting, however, is that 49-59% of women reject this stereotype, rising to 70% in the post-1990 generation. There are far fewer role models in China to prove that “women can do politics too”; if 70% of the youngest generation reject the men-first stereotype, this is possibly more thanks to the feminist movement and particular causes célèbres, as well as emergent women’s communities online. Men of the same generation have not enjoyed the same enlightened and supportive climate, which accounts for this generation’s enormous gender gap.

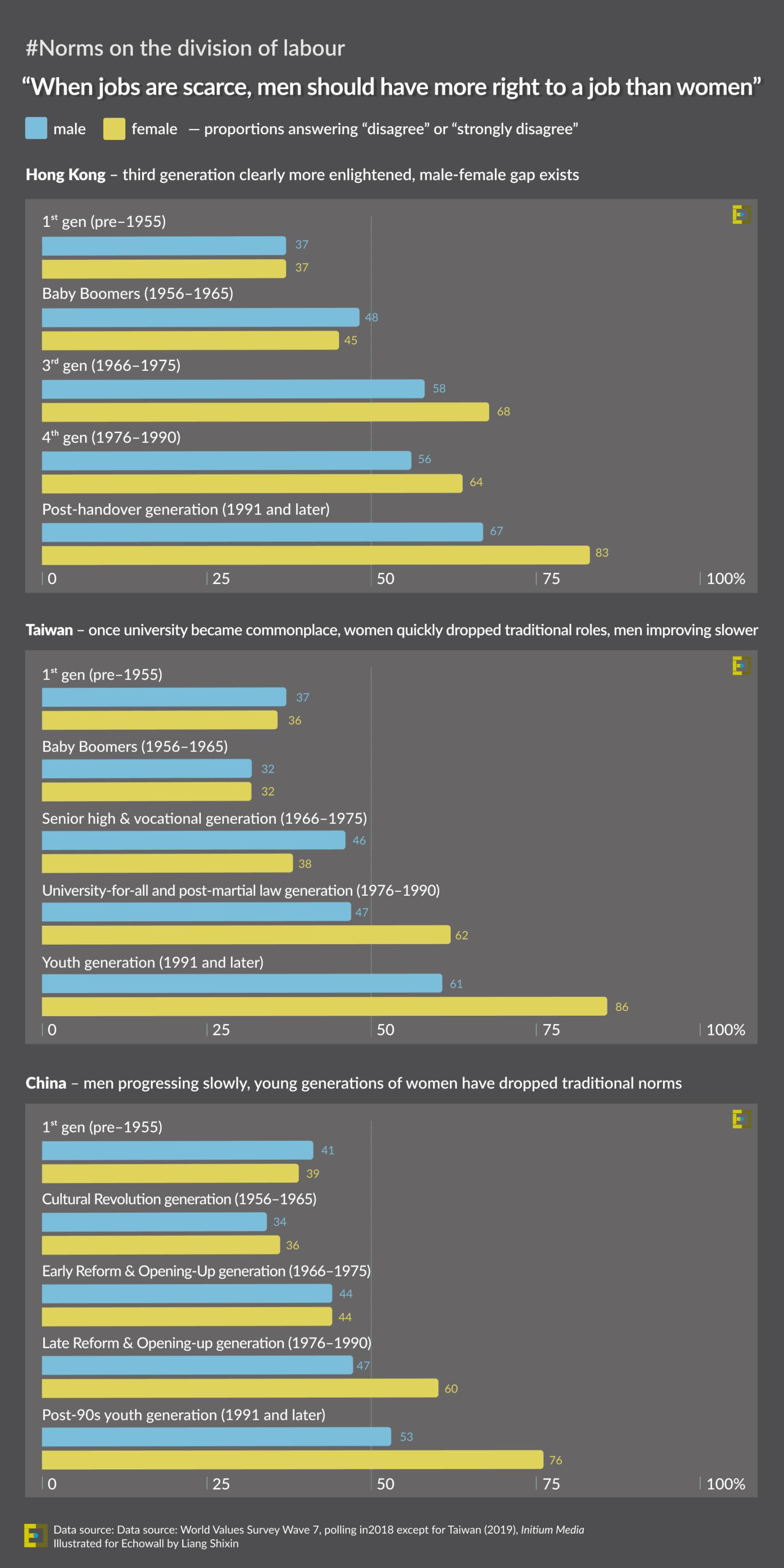

2: Do mainland Chinese, Hong Kong, and Taiwanese people think that “when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women”?

This question measures support for the traditional labor norm that sees men as breadwinners and women staying at home; given how mainstream it is by now for women to have jobs, the question contains the proviso “when jobs are scarce” to see if respondents feel women should yield the reins to men and give them a kind of ‘breadwinners’ priority.’

On this issue, the sexes in Taiwan and Hong Kong are no longer in lockstep; women have been have been progressing faster than men. In China, a significant discrepancy is that women are much more progressive.

Even in 2018/19, 60-70% of men and women in Hong Kong and Taiwan agree with the statement – however, the mainstay of the workforce, the generation born from 1976 to 1990, sees over 60% of women disagreeing, rising to over 80% of post-1990s women. Men in Hong Kong and Taiwan are still more supportive of gender equality than older generations: close to half (Taiwan) or over half (Hong Kong) when it comes to the 1976-1990 generation, rising to over 60% of the post-1990s cohort, but a gender gap is emerging since they are becoming progressive at a markedly slower rate than their female peers.

In other words, Hong Kong and Taiwan’s two youngest generations are more progressive than their male and female predecessors regarding gender stereotypes and labor roles. While they are moving in lockstep on gender stereotypes, they are moving at variable speeds on the issue of labor norms. Why has this gap appeared? Perhaps because new generations in Hong Kong and Taiwan have plenty of successful female leaders to look to, disproving the old stereotypes; the ideal ‘division of labor between the genders’ is more of a question of values, and values are less likely to be challenged just by the existence of objective facts. Only life experience and education can shift them.

Education and employment prospects for young women are getting ever better in Hong Kong and Taiwan, with the vast majority able and motivated to forge their careers, so the old norms do not count for much in their eyes. Many men don’t have the same lived experience, except in cases where they have helped women around them overcome pressure from traditional norms; for the most part, though, only education and culture shift their values, and it is a slow one. The question also feels less ‘vital’ to men, given that traditional norms call for women to be subservient to them; a considerable cohort of the former still cling to outdated gender norms as a result.

The picture looks similar in Hong Kong and Taiwan, except for one huge caveat: post-1990s women are more progressive than their forebears in both, but third-generation women in Hong Kong (born between 1966 and1975) long ago were rejecting traditional gender norms by over 60%, similar to their fourth-generation successors. In contrast, this phenomenon did not occur in Taiwan, where only the latter generations have awakened their consciousness. In other words, the ‘enlightened generation’ of Hong Kong women was earlier than in Taiwan. The reasons for this merit careful study – although women’s employment and career experiences tend to be the main drivers of mentality shifts, Taiwan saw a more considerable proportion of women attending university than men as early as 1988, earlier than Hong Kong (1998), so expanded higher education cannot suffice as an explanation of why Hong Kong women born in 1966-1975 gained a firm consciousness that their Taiwan peers still lacked and mainly threw off gendered labor norms one generation earlier.

Once again, it is an entirely different picture in China. Like gender stereotypes (see above), men have been slowly progressing; however, women, especially the generation of post-1990, do not identify at all with the old labor norms of their mothers’ generations; the results: another huge gender gap of 25 percentage points within the youngest generation. As discussed above, gender equality has seeped into the youngest generation of women’s mindsets but has had less effect on their male peers.

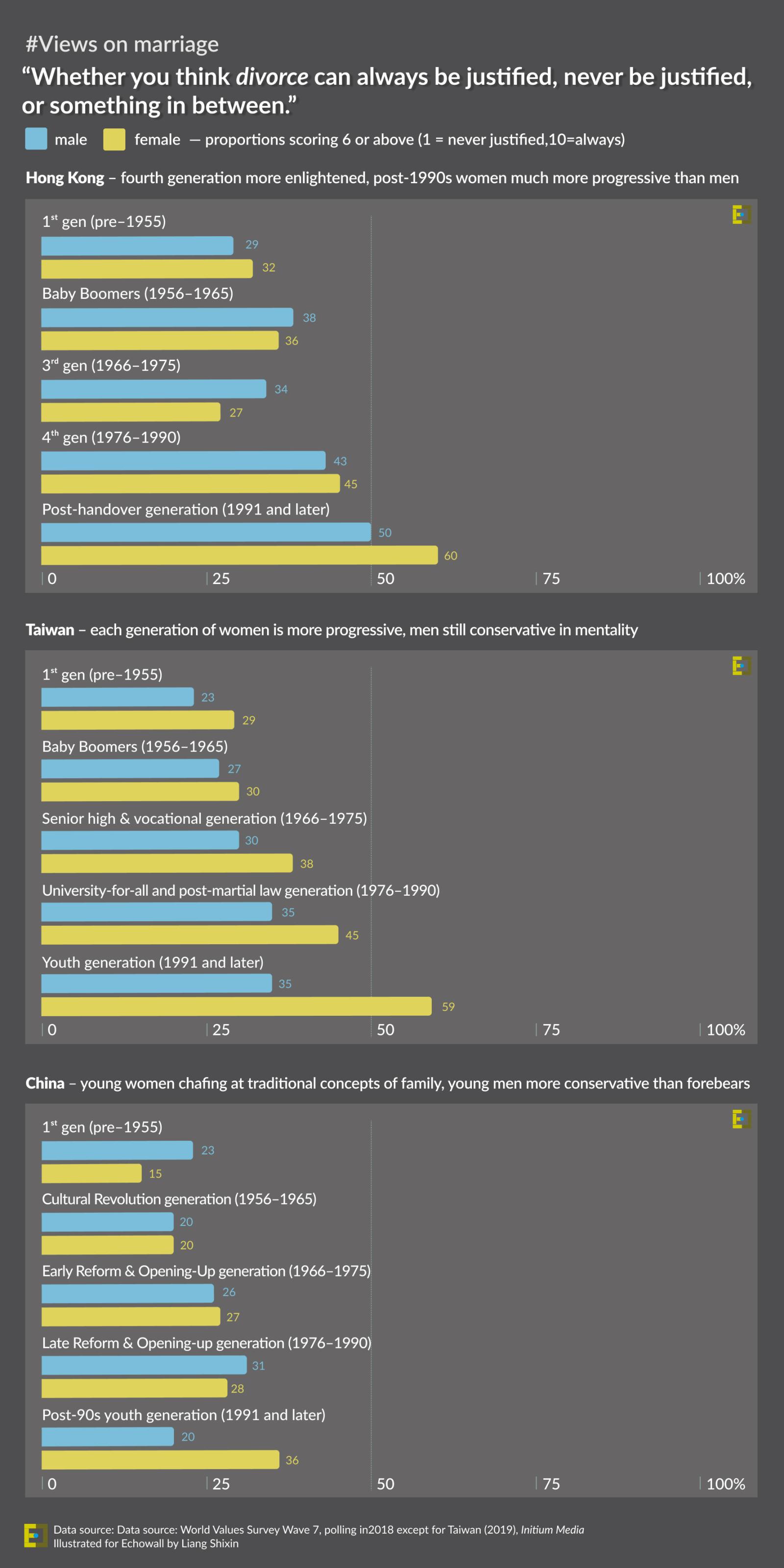

3: In mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, do people think divorce is justified?

The third and final survey question was, “[can divorce] always be justified, never be justified, or [is the answer] something in between?”. Respondents needed to answer on a scale of 1 to 10, 1 meaning “never justified” and 10 “always justified.” A score of 6 or above is considered a relatively progressive position.

On the face of it less about gender equality than monogamy and ‘marriage till death us do part’, this question hinges on whether people feel someone should endure unhappiness and even danger rather than at some point escaping their marriage. Of course, there are plenty of men trapped in unhappy marriages too, but many more women suffer at the hands of their husbands and the latter’s relatives; the hazards and opportunity cost of staying in the marriage are all the higher for them, so this survey question is very much one about gender equality.