Original illustration by Tse Yuet Ching.

Searching for a Bolder China Policy

French President Emmanuel Macron has spoken of "boldness," "risk-taking" and the upholding of Enlightenment values as essential to foreign policy. But far from boldness, the current strategy toward China in Paris seems one of avoiding offense at all cost.

In August 2019, President Emmanuel Macron defended to his ambassadors a "strategy of boldness, of risk-taking" in French foreign policy. His argument was essentially that as “the international order is being disrupted in an unprecedented way, with massive upheaval, probably for the first time in our history, in almost all areas and on a historic scale,” France should not choose to be just a spectator, but must act instead as a balancing power in the midst of disruptions that threaten European values – and as the world centered around the two main focal points of the United States and China. In regards to China, Macron said that earning the country’s respect meant, first and foremost, taking “a European approach” to the changing world, particularly as China had shown a “a real diplomatic genius for playing on our divisions and weakening us.”

Macron's bold language was an echo of what he had said on the night of his election as president in 2017: "Europe and the world are waiting for us to defend the spirit of the Enlightenment that is threatened in so many places. They are waiting for us to defend freedoms everywhere, to protect the oppressed."

Given his bold rhetoric last year and throughout his term, Macron was taken to task in late August this year as he failed to hold a public press conference with visiting Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to openly state French concerns, including about the situations in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. This was a noted contrast to Italian, Dutch and German officials who were much more direct in their criticisms. The French president reportedly did air his “strong concerns” in an internal meeting with Wang, but was this really boldness?

2020 has been a year full of challenges in China-France relations, stemming from tensions over the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the issue of the Chinese tech giant Huawei and 5G, and questions over Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Taiwan, not to mention issues related to trade, climate policy and so on. In the face of these challenges, how has Macron’s “strategy of boldness, of risk taking,” held up? To answer this question, we must go back over President Macron's ambitions regarding China, and take a closer look at France's China policy and its concrete, albeit sometimes limited, achievements.

Imperfect Communication

Foreign Minister Wang Yi's trip to Europe in August 2020 was motivated more by questions of form than substance. For this reason, it was essential that the French counterparts gave special attention to their public communication, ensuring that French positions were publicly conveyed. And yet the communication errors, particularly those committed by the Elysée Palace, the presidential office that drives French foreign policy, gave the impression that complacency on the French side was aiding China’s communication agenda, or even fueling its propaganda – all without leading to the slightest announcement on the bilateral level.

This sequence of events in fact highlighted the broader problem of hyper-centralization of decision-making on foreign policy matters at the Elysée, as well as human resource issues within the diplomatic office, including frequent staff departures and burn-outs – including of the adviser in charge of the Americas and Asia in August 2020 – in what one commentator recently characterized colorfully as “French diplomacy on the verge of a nervous breakdown.”

One key issue in the bilateral relationship, which came up between President Macron and Wang, has been the systemic aspect as well as the lack of reciprocity in senior-level meetings. On the French side, Emmanuel Macron has received Wang Yi on each of his four visits to Paris – in May 2018, January and October 2019, and August 2020. On the other side, France’s minister of foreign affairs, Jean-Yves Le Drian, has never secured a meeting with Xi Jinping, having met only with Yang Jiechi, director of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission of the Chinese Communist Party, which has general oversight of foreign affairs in China, during one of his three visits to Beijing.

French Minister of Foreign Affairs Jean-Yves Le Drian has made three visits to China, but aside from a de facto meeting during Macron’s visit has never had a bilateral meeting with General Secretary Xi Jinping. Image available at Wikipedia Commons under CC license.

France has repeatedly urged reciprocity at all levels as a priority, and yet China has proved resistant and France unsuccessful. It should also be recalled that since 2018 President Macron has committed himself to visiting China every year, a diplomatic courtesy he has not extended to any other country. This has further exacerbated the asymmetry of the French negotiating position, leaving Paris in a position during each successive visit to negotiate Chinese concessions, even if these are small and mostly cosmetic. One could then wonder if France has been bold enough with China diplomatically.

As mentioned previously, another communication failing on the French side during the Wang Yi visit was the lack of mention of the sensitive issues of Hong Kong and Xinjiang publicly in front of the media. While no press conference was held in Paris, the Italian, Dutch and German leaders did raise their concerns in press conferences. Moreover, during Wang Yi's speech at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI), journalists were not permitted to ask questions, a seeming nod to Chinese demands that in fact raises questions about the role of think tanks in free societies like that of France. Should they not exist to provide open and critical platforms for discussion, being integral to sound policy-making?

The absence of public statements on the French side in the wake of President Macron and Wang’s meeting was a communication mistake that left Beijing free to impose its elements of language which were then widely taken up in the international press.

The Quai d'Orsay press release, an account of the meeting between Jean-Yves Le Drian and Wang Yi released on August 30, mentioned only at the very end that “[the] minister recalled France's serious concerns about the deterioration of the human rights situation in China, in particular in Hong Kong and Xinjiang.” But neither the president nor the minister spoke publicly in front of the media about their concerns, and this attracted criticism from many Europeans.

The absence of public statements on the French side in the wake of President Macron and Wang’s meeting was a communication mistake that left Beijing free to impose its elements of language which were then widely taken up in the international press. This problem was compounded as the Elysée had also failed, after previous meetings between Wang Yi and Macron’s diplomatic adviser, Emmanuel Bonne, to issue any communiqué.

In May, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a read-out of a phone call in which Bonne was quoted as saying he “appreciated the sensitivity of Hong Kong-related issues,” and affirmed that “France hoped related issues would be properly resolved under the “one country, two systems” framework.” The Chinese release effectively preempted communication from the Elysée Palace, which had failed to publicly express its concerns on the deterioration of the situation in Hong Kong publicly at a crucial time.

A May 2020 release from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs reports a telephone exchange between Wang Yi and Macron’s foreign policy advisor, Emmanuel Bonne.

The read-out also mentioned that Bonne had noted “the tensions and misunderstandings in the international community caused by COVID-19,” giving the further impression that Bonne had supported the idea that China was a misunderstood and benevolent country. In fact, just one month earlier, Le Drian had summoned the Chinese ambassador to voice his extreme disapproval after the China Embassy had published a communique spreading disinformation and slander over France’s handling of COVID-19 and some French MPs. The Chinese communication strategy is yet obvious, benefit from asymmetry in communication to silence disputes and portray a positive image of China.

In a European context, such communiqués may not be regarded as necessary following meetings between European partners. However, it is essential with regard to diplomatic meetings with powers, such as China, that are engaged in what Josep Borrell, the current High Representative of the European Union, back in March called the "global battle of narratives."

High Ambitions, Low Results

The Franco-Chinese relationship is often presented as a being unique due to a number of "historical firsts" between the partners. In 1973, French President Georges Pompidou became the first Western head of state to visit China since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. France was also the first major Western country to establish formal partnerships with China, including a "global partnership" in 1997, and a "global strategic partnership" in 2004. In 2001, France became the first to organize a strategic dialogue with China, followed in 2004 by the United Kingdom (2004), in 2009 by the United States, and in 2010 by Germany. Despite its historical firsts, however, China’s bilateral relationships in Europe have gradually normalized, and France today enjoys no clear advantage over its European counterparts in this respect.

From his first state visit to China in January 2018, Macron sought to underline his pragmatism and lay the foundations for a more reciprocal bilateral relationship. Visiting the northwest Chinese city of Xi'an, which once formed the eastern end of the network of trade routes later called the “Silk Road,” the French president stated in reference to China’s ambitious global development project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), that “silk roads . . . cannot be the roads of a new hegemony that would somehow put the countries they traverse in a state of vassalage." By that point, the BRI, launched more than four years earlier, was already the subject of some controversy in Europe, with concerns over transparency in public tenders for infrastructure projects, a flood of Chinese investment into the EU and other issues. During the 2018 visit, Macron’s economic minister added that France would oppose "investments of plunder.”

More than a year later, in March 2019, Macron sounded a strong note on the fringes of a European Council meeting, stating that "the time of European naivety" was over in regards to relations with China. His words were a call for greater vigilance, for European states to wake up to the longer-term implications of geopolitical or strategic dependence on China. The traditional focus on trade was no longer enough, he said, and he cited China’s formation of the “16+1” group of nations in Central and Eastern Europe – now the “17+1” with the addition of Greece in 2019 – as a worrying example of its political ambitions on the continent.

The theme of dependence featured strongly in Macron’s criticisms again this year, as the global COVID-19 pandemic, both a health crisis and an economic crisis, exposed “flaws and weaknesses” for Europe, including what the president called "our dependence on other continents to provide us with certain products." The president referred to a Franco-German proposal for a 500 billion Euro Recovery Fund to help turn the continent’s economy around as an “historic turning point,” paving the way for a more assertive Europe – toward both the US and China. "This could be an unprecedented step in our European adventure and the consolidation of an independent Europe that gives itself the means to assert its identity vis-à-vis China, the United States and the global disorder that we now see."

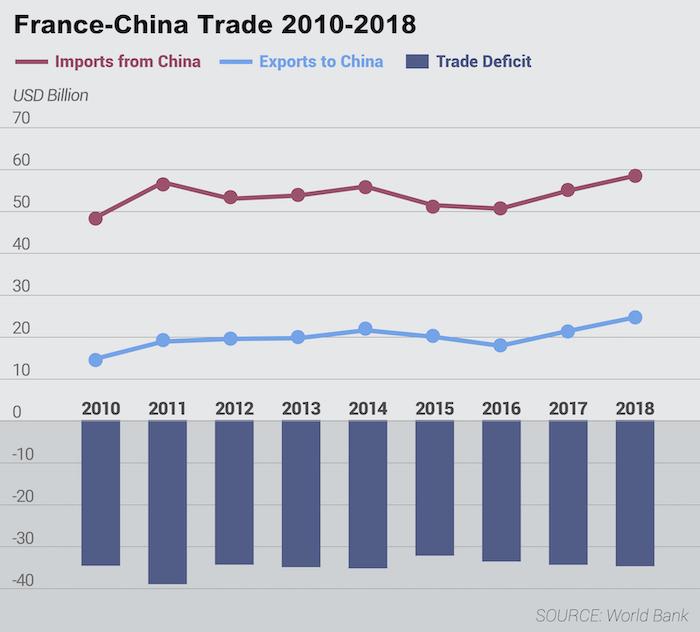

Economic exchanges and the fight against climate change are two priority areas in the bilateral relationship Macron seized on early on in his presidency, both tied directly to his national priorities. On the economic side, there have been some noteworthy advances – beyond the traditional signing of mega contracts for Airbus. For example, Paris has obtained the total lifting of the embargo on French beef, first instituted by China in 2001. It has pushed at the European level for a successful agreement ensuring the protection of 100 European food products, 26 of them French, and as many Chinese products. Excluding aeronautical equipment, we should also note an increase in the export of French to China in 2019, up 7.4 percent year-on-year, and favorable numbers for the export of agricultural and agri-food products, up 17.8 percent.

Despite these rare bright spots on trade, however, structural and pre-existing problems in the bilateral relationship persist, even as the Elysée has made it its mandate to promote "the principles of market access, fair competition, reciprocity and reduction of trade tensions."