How Dependent is Germany on China?

The importance of the trade relationship with China has encouraged the view in Germany that economic dependencies limit its choices in areas like human rights. But closer scrutiny suggests this might not be the case.

In the midst of the Covid-19 epidemic, Germany's dependence on China has been a topic of interest and discussion among the German public. Dependence on China, particularly in the production and supply of essential medical products, has been cause for widespread consternation.

Even before the crisis, however, the phrase "Germany's dependence on China" and related terms had become familiar expressions playing an important role in framing the bilateral relationship in the German discourse. This report evaluates media articles published in Germany since 2017 and compares them with publicly accessible data and sources (German, Chinese and English), answering the following questions:

- How did the China dependency narrative emerge, and how has it developed?

- What do we mean when we talk about dependency? What are the central key elements?

- How these elements correspond to complex issues in the bilateral relationship?

- What important aspects have been omitted from consideration in the development of the narrative?

- What new dynamics did the Covid-19 pandemic introduce to the discussion?

Key Points:

Germany’s trade volume with China overtook that with the US for the first time in 2016. When Trump imposed tariffs on Germany in early 2017, the German public was delighted to have China replacing the US.

The importance of trade with China is framed as a one-sided dependency of Germany on China, which does not match the complexity of the bilateral trading relationship.

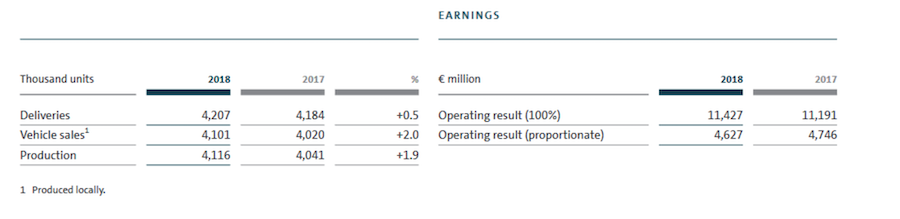

The most-used example for this dependence is that Volkswagen sells four million cars in China per year. However, as the capital is highly globalized today, the question is whether these transnational companies can still be viewed as “national champions.”

Instead of fearing or blaming China, Germany needs critical self-reflection in terms of environmental and other standards in the supply chain, investment in domestic education, and seeking a European answer to the China question.

The Story of a Narrative

In the preliminary search, it was clear early on that a supposed causality had been established across the German media, based on the unquestioned belief that China is Germany's most important trading partner. According to this logic, China’s top trading status results in Germany’s economic dependence on China, and the most frequently mentioned example of this dependence is that Volkswagen sells more than four million cars to the Chinese market every year (out of ten million deliveries worldwide). The dependence in turn makes it difficult for the German government to take clear positions on issues like human rights, or restrictions on Chinese FDI.

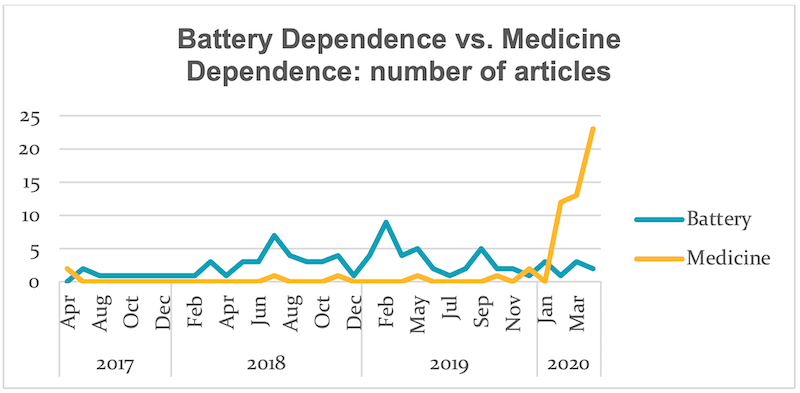

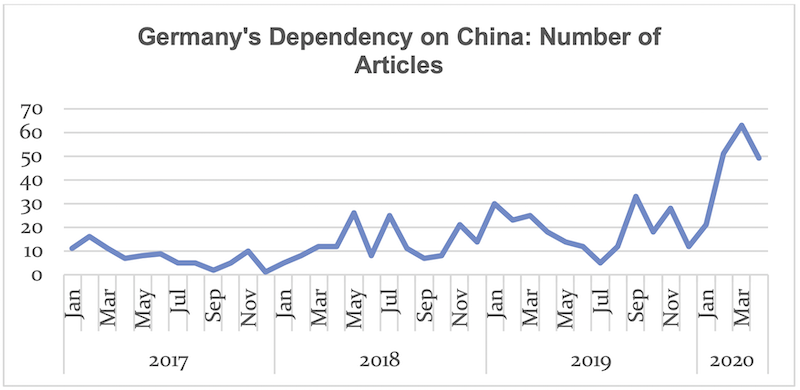

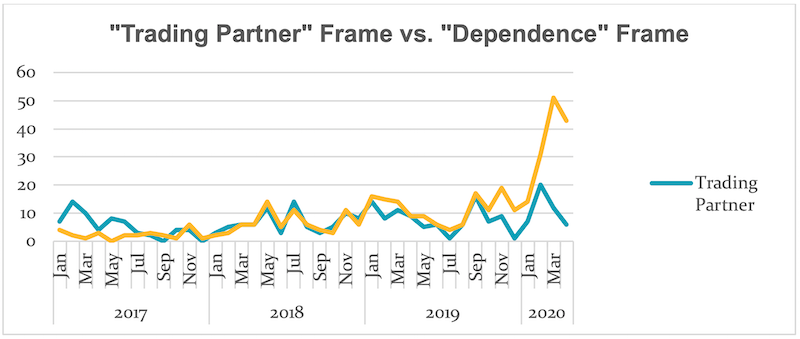

For this study, articles from six influential media outlets were evaluated for the period from January 1, 2017, to April 18, 2020: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ, including FAZ.net), Handelsblatt, Der Spiegel (including Spiegel Online), Die Welt (including Welt Online), Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ), and Die Zeit (including Zeit Online). Two German key words were used: "abhängig*" (dependent*) and "Handelspartner" (trading partner). Programs from the German television station ARD are cited, but are not included in the quantitative data. The total data range includes 661 articles. The following graph shows total articles in the media set since 2017, with a notable increase since the outbreak of the corona pandemic.

China Takes the Top Spot

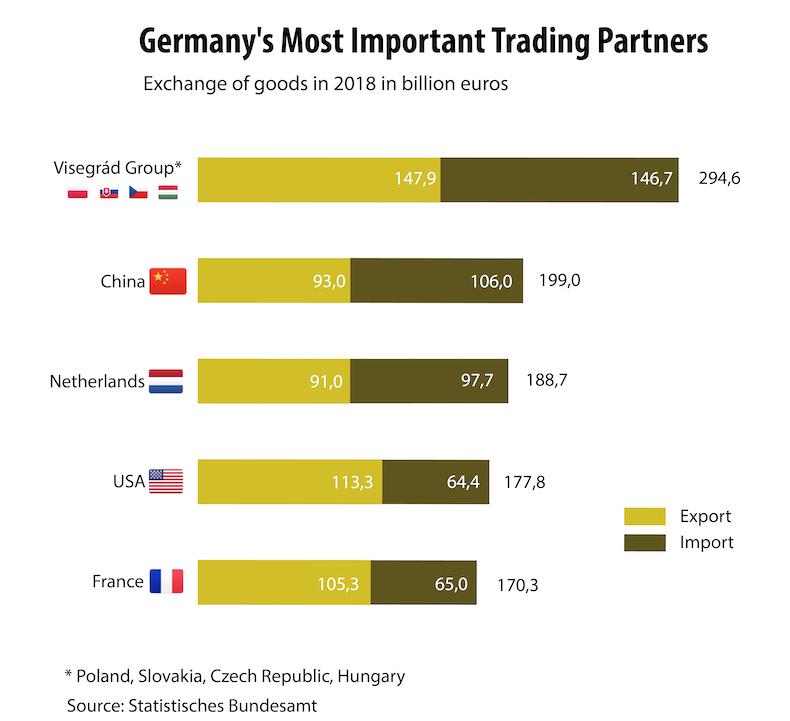

In 2016, Germany's trade volume (imports and exports together) with China overtook that between Germany and the United States for the first time, making China Germany's largest trading partner. The figures were first announced in late January 2017 by the German Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DIHK), and again in late February by the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Statistisches Bundesamt), and the change in the rankings ignited enthusiasm in the German press.

On January 27, 2017, the headline in Spiegel Online read: "China is Germany's new number one." The report argued that while Donald Trump was closing off the US market, China was rising up to become a new trading superpower. Spiegel Online stated that, "In relation to Germany, the People's Republic has now already reached the top position." On February 24, 2017, Spiegel Online gleefully reported, in an article with the headline, "America Third," that the German economy had "shifted its priorities" and that the US was "no longer the first destination" for trade.

SZ also used the term "number one" to frame China's new position. In this regard, too, the article emphasized that, for Germany, the importance of the US was declining. On February 24, 2017, both FAZ and Zeit Online published articles with nearly identical headlines, including the statement, "China is replacing the US as the most important trade partner." In addition to two reports about China as Germany’s most important trading partner published in January and February, Die Welt also published a guest article in late January written by then Chinese Ambassador Shi Mingde, in which he wrote that for the two economies "win-win is the solution."

The importance of the new ranking of trade partners will be discussed in the second part of this article. But the psychological impact of the change was enormous. Following Donald Trump’s inauguration on January 20, 2017, threats of punitive tariffs against important US trading partners such as Germany and China became a reality. For German economic and political decision-makers, this was deeply unsettling. At the World Economic Forum in Davos on January 17, 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping presented himself before more than 1,000 influential global economic elites as a "guarantor of globalization and free trade" (Handelsblatt), in sharp contrast to Trump.

Beijing used this opportunity to launch a "charm offensive towards Europe and Germany," which was well-received. In February 2017, China announced that it would postpone a statutory sales quota for electric cars by one year, following intervention by the German government and in favor of the German carmakers Volkswagen, Daimler and BMW, which all have production facilities in China. Almost euphorically, Handelsblatt commented:

Since Donald Trump has set the US administration on a more protectionist course at the White House, China and Germany have sought to join forces. Both Beijing and Berlin have a strong interest in advancing globalization and free global trade [...] The two countries are highly interdependent. China became Germany's most important trading partner for the first time in 2016.

In this context, it is perhaps not surprising how quickly the notion of China as the most important trading partner established itself among the German public. The Federal Statistical Office of Germany publishes trade data every February. For this reason, the phrase “the most important trade partner” makes a regular appearance in the German media each year between the arrivals of Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny. The phrase is also used frequently during state visits between the two countries. Xi Jinping is one of the most prominent advocates of the notion of a trading partnership, and in July 2017, Die Welt published his guest article, "For a better world," on the occasion of the G20 summit in Hamburg.

President Xi Jinping presented himself before more than 1,000 influential global economic elites as a "guarantor of globalization and free trade."

Fearing the Middle Kingdom

While the term "partner" tends to convey a positive impression of trustworthiness and mutual benefit, the term "dependence" often bears more menacing connotations. As the following graph shows, in 2017 the phrase "the dependence of the German economy on China" was rarely the topic of discussion between Germany and China. But in 2018, the topic continued to grow.

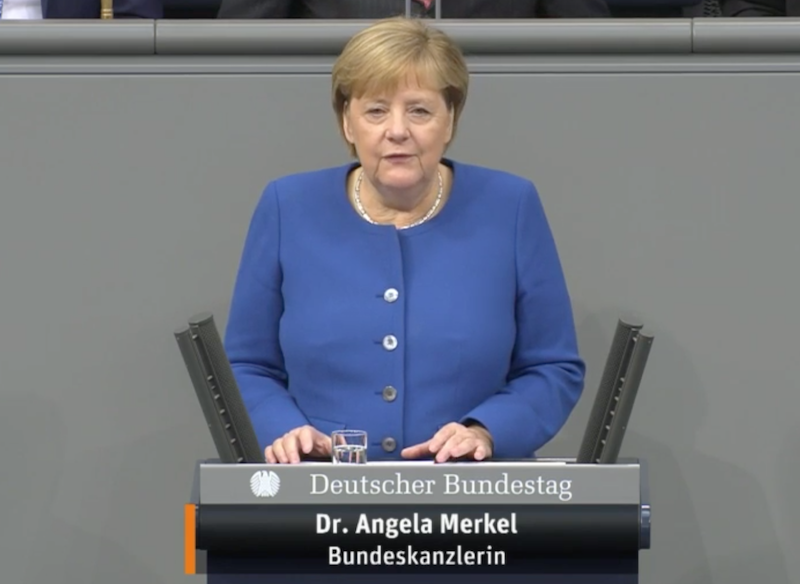

When Angela Merkel visited China to negotiate the reciprocity of bilateral economic relations in May 2018, media reports focused on her "delicate mission in Beijing" (Die Welt). On the one hand, German companies complained about market obstacles and forced technology transfer in China. On the other hand, Chinese direct investments in Germany had risen sharply (from 80 billion in 2013 to 180 billion in 2017). The focus of Chinese purchases on Germany’s high-tech sector aroused concern. "Beware of fast money from China," warned Die Welt. Der Spiegel, meanwhile, characterized Merkel's mission as “negotiation with the Leviathan." Since then, "fear of the Middle Kingdom" (FAZ) has prevailed among German business elites. Words like "fear," "anxiety," “worry,” "danger" or "threat" occur in over 60 percent of the articles examined in this study, conveying the dominant mood within the narrative of German dependence on China.

Due to fear of losing out in the "systemic competition" against "China's state-dominated economy," the Federation of German Industries (BDI) warned against "too much dependence on the Chinese market" in a position paper at the end of 2018. Meanwhile, Germany’s other leading organization of the economy, the German Chambers of Commerce and Industry (DIHK), continued to advocate "change through trade" in its own China action plan. Nevertheless, a statement by Volker Treier, DIHK head of foreign trade, conveyed a sense of fear, not a sense of confident partnership: "We must always remember that China is our most important trading partner. We have to weigh every word on the gold scale," he said.

From September 2019 until the end of the year, the debate on Germany’s dependence on China remained intense, further triggered by the protests in Hong Kong. Both the German government and large German companies came under public pressure, facing criticism for not taking clear positions against police violence on the ground out of an urge to protect their economic interests with China.

From October, another domestic political issue was added to the dependency debate – the role of the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei in the development and construction of the German 5G network. The German government released a rule book for the 5G network security, but despite the efforts of the US government to press for a ban on the Chinese company, Huawei was not explicitly excluded. This decision sparked fierce debate among political and economic decision-makers. While critics mainly argued the dangers of "technology dependence” on a company they said could not be trusted geopolitically, counter-arguments often turned again to the narrative of German economic dependence on China. According to Der Spiegel, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel feared that "an all too harsh course could provoke retaliatory measures by the Chinese against German companies investing in or exporting to China."

The German discussion in the media on relations with China gives the distinct impression that Germany is helpless and incapable of action. Media reports spoke of Germany facing a "Huawei dilemma," a "Hong Kong dilemma," or a "China dilemma." Or Germany was in a “trap,” or “quandary,” squeezed “between the fronts” of the US and China, and "crushed" by the two superpowers.

In the period leading up to the Covid-19 crisis, one issue of concern was particularly salient, with strong calls for action. This was about Germany’s struggle against dependence in the electric-vehicle battery (EVB) sector. At present, EVB production is dominated by companies from East Asia, including Chinese ones. Media coverage has suggested this is a matter of life or death for the German economy. Up to the end of 2019, half of the articles in Handelsblatt using the keyword "dependent" (abhängig) dealt with this topic. "I find it frightening that we have fallen into such great dependence," said Volkswagen CEO Herbert Diess. However, one report from FAZ commented that the course suggested by Diess would in fact make the group even more dependent on the Chinese market.

Volkwagen's decision in 2019 to produce its own batteries in Germany was welcomed by various parties. Volkswagen made demands to the politicians to be exempted from the renewable energy levy (imposed by the German Renewables Act). Trade unions also supported the idea of domestic battery production. FAZ tersely summed up this determination with the statement, "My car, my battery, my factory." Only one article, in Die Zeit, criticized a promise by Federal Minister for Economic Affairs Peter Altmaier of one billion euros of public money to the automobile industry. The article called instead for investment in materials research.

The Covid-19 Domino Effect

The graph below might seem somewhat ironic if it were not for the extremely tragic nature of the Covid-19 epidemic. Since the virus outbreak in Europe, there is very little interest in the issue of German manufacturing of EVBs. The discussion has turned sharply to shortages in pharmaceutical production, which is strongly dependent on China and suffered severe disruptions at the end of January due to nationwide quarantines imposed in China, which paralyzed production across industries.