Federica Mogherini, High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. Photo copyright "©European Union" available at European Council newsroom.

Troubled Waters

The European Union has moved toward closer defense cooperation with Southeast Asian nations in light of China's increasingly aggressive behavior in the South China Sea. What does the new agreement signed between the EU and Vietnam this month actually mean? And what is at stake?

Earlier this month in Hanoi, Federica Mogherini, the European Union's foreign policy chief, signed an agreement between the EU and Vietnam that paves the way for closer defense cooperation. The agreement is a further sign of increasing European engagement on security "in and with Asia," and it is in large part a response to the challenges China now poses to the existing order.

During her visit, Mogherini said that "increasing tension" in the South China Sea, was of urgent concern to the EU. "We believe that this tension, this militarization," she said, "is definitely not conducive to a peaceful environment."

Since 2015, China has busied itself building artificial islands in disputed areas of the South China Sea, installing military facilities, exploiting oil and gas reserves, and driving away vessels from Southeast Asia countries that have a right to operate in the waters according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and a 2016 ruling by the Hague Tribunal.

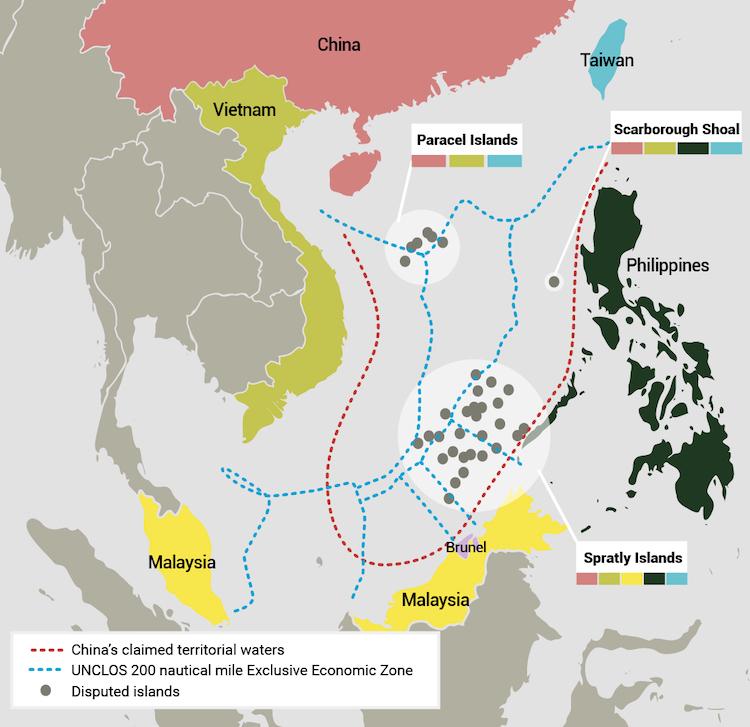

Beijing claims that it has “historical maritime rights” on the basis of what it calls the "nine-dash line," going back to territorial claims in the sea made in 1947 by the Republic of China. According to this definition, China claims an area covering as much as 90 percent of the contested waters in the South China Sea, and running very close to the coasts of the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam. These claims emphasize China's sovereignty over territorial features, such as islands and reefs, within the area.

The above map shows competing claims to territorial features in the South China Sea. In the map legend, we have labelled the area within the so-called "Nine-Dash Line" as "China's claimed territorial waters." Bill Hayton has suggested instead the phrase "China's ambiguous claim line," as there is very little clarity outside China about what this claim even means. Map created by Alice Tse.

With roughly one-third of global trade passing through the South China Sea, freedom of navigation is an issue of strategic concern for all trading nations. The United States has increased freedom of navigation operations (known as FONOPS) in the South China Sea in recent years, and one year ago, on August 31, 2018, the Royal Navy's HMS Albion passed through the Paracel Islands, the first known British attempt at a freedom of navigation operation.

What is at stake for Europe in the South China Sea issue? Nicola Casarini, a senior fellow at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) in Rome, wrote last year that "Beijing’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea is putting Europe’s economic interests in the area at risk."

"More than one third of Europe’s external trade takes place with the Indo-Pacific region," Casarini writes, "and any escalation of tensions in this area will undoubtedly have a direct impact on Europe."

For more insight on the recent agreement between Vietnam and the EU, and on the implications of the South China Sea issue for Europe, Echowall sought out Bill Hayton, author of South China Sea: The Struggle For Power in Asia, and a long-time observer of security issues in the region, and Dr. Felix Heiduk, an expert on defense and maritime security at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP).

________________________________

Bill Hayton. Image from Chatham House.

Bill Hayton, Associate Fellow Chatham House Asia-Pacific Program, Author of South China Sea: The Struggle For Power in Asia

Echowall: On August 5, Federica Mogherini, the EU's foreign policy chief said during a visit to Hanoi that "increasing tension" in the South China Sea was a concern for the EU. I wonder if you could start by summarizing your take for European readers of the situation. What has been happening in the South China Sea, and why are China's sovereignty claims there of concern to Europe?

Hayton: Since late May 2019, China has been using coercion to try to force Vietnam and Malaysia to give up rights to their offshore oil and gas resources. Chinese vessels have manoeuvred aggressively around Vietnamese and Malaysian oil rigs and ships and then deployed in large numbers to block off large areas of sea. China is doing this in order to compel these two countries – along with Brunei, Indonesia and the Philippines – to agree to what China calls "joint development." China’s idea of joint development is that it gains the right to extract a share of these countries’ maritime resources regardless of international law.

When pressed to justify its behavior at the China-ASEAN summit meeting in July, the Chinese foreign minister claimed that the areas where the confrontations were taking place were "disputed" between China and the other countries. In other words, he argued that there were overlapping claims to the maritime resources and that China had at least as much right to them as Vietnam or Malaysia. However, he gave no details of the exact basis of China’s claim.

Arguments like this are supposed to be resolved according to an international treaty agreed in 1982. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) gives countries rights over the resources in the sea off their coasts. To simplify things a little, a country has exclusive rights over the fish swimming in the sea and the minerals under the seabed up to 200 nautical miles (about 400 km) away from their coastline. This area is called an Exclusive Economic Zone or EEZ. Almost every country in the world has ratified UNCLOS and has agreed to be bound by its rules. (The major exception is the United States.)

The complicating factor in the South China Sea is the presence of dozens of tiny islets in the waters between Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines. These are known collectively as the Spratly Islands. UNCLOS says that an island can generate an EEZ if it is able to sustain "human habitation or an economic life of its own." There is no precise difference between a "rock" and an "island" but in July 2016 an International Arbitral Tribunal ruled that none of the Spratlys were full islands. They are all far too small and inhospitable to support human life for any length of time.

Photograph from the International Space Station of the South China Sea which includes the Cresent Group and Discovery Reef features. Public domain image by NASA-Johnson Space Center.

Since China’s mainland coast is well over 1000 kilometers from the areas under dispute, this cannot be the basis of its claim. The only likely explanation is that China is claiming an EEZ from the Spratly Islands. This would be a contradiction of the Arbitral Tribunal’s 2016 ruling. However, that ruling is only binding on the country that brought the case, the Philippines, and the country it was brought against, China. For Vietnam and Malaysia to benefit from it, they would have to bring their own cases against China. So far, they have been unwilling to do so.

European interests are at stake in the dispute. Some of the energy companies damaged by China’s behavior are European. Repsol of Spain was targeted by China in 2017, 2018 and again this year. Shell of the UK and the Netherlands is affected by the current action off [the coast of] Malaysia. Other European companies have interests in nearby areas at sea that could be jeopardized by China’s actions.

At least as importantly for Europe, what China is doing seems to be in violation of UNCLOS. The EU believes that international rules and agreements are a vital constituent of international peace. When they break down in one part of the world, they are weakened everywhere. If China continues to flout UNCLOS in the manner that it is currently doing then other countries may also decide to break the bonds of self-restraint that international law creates. The result, ultimately, would be a free-for-all where might beats right. That would be very bad for international peace and security all around the world.

The result, ultimately, would be a free-for-all where might beats right. That would be very bad for international peace and security all around the world.

Echowall: One EU official mentioned in the context of the EU-Vietnam agreement the importance of "safeguarding the rules-based multilateral order." Based on its actions in the South China Sea and globally and its public statements, what can we say about how China regards the international rules of the sea?

Hayton: China ratified UNCLOS in 1996 and makes use of many of its provisions. It has passed laws claiming a Territorial Sea and an Exclusive Economic Zone for example. It also makes use of the ‘freedom of navigation’ principles laid down by UNCLOS to send its naval ships around the world. A Chinese destroyer passed through British territorial waters in the English Channel in August, making use of the rule known as "innocent passage." China has sent intelligence-gathering vessels into the waters near the American military bases in Hawaii and Guam, as is permitted under UNCLOS. However, it has also tried to block British and American vessels from exercising exactly the same rights in the South China Sea.

In April 2018, I asked Senior [PLA] Colonel Zhou Bo [director of the Center for Security Cooperation at the Office for International Military Cooperation in China’s Ministry of National Defense] about this double standard at an event at Kings College, London. His reply was very surprising. He said, “We follow your laws and you should follow our laws.” In other words, there is no such thing as international law with rules that must be followed everywhere. In Colonel Zhou’s view, the fact that China has a domestic law requiring foreign military vessels to ask permission before entering the country’s territorial sea takes priority over its international treaty obligations. The threat to international law is obvious.

Echowall: During her visit, Mogherini signed a defense agreement with Vietnam that some called historic - the first EU defense agreement in Southeast Asia. How significant do you think this agreement is, and can we expect other agreements like this between the EU and smaller nations in the region? What is the thinking right now in Brussels?

Hayton: I think that the agreement is very significant in that it sends a message that the EU regards Vietnam as upholding important international principles that other states should follow. It follows the recent ratification of the EU-Vietnam free trade agreement, so it is another sign of strengthening ties between the two. However, it is important not to overstate what the defense agreement says. The EU is not about to get militarily involved in the South China Sea disputes. This is about helping Vietnam to take part in peacekeeping operations and other activities related to international security.

I think the EU wants to send a message to China about the importance of upholding international rules, of the peaceful settlement of disputes and of Europe’s vital interests in both those principles. The problem is that Xi Jinping’s China doesn’t seem to care too much about what other countries think.

Echowall: Some have suggested that the defense deal should just be the beginning, and that the EU should expand its actions in Southeast Asia, following the U.S. and Japan, which have helped nations in the region build up their Coast Guard forces in recent years, for example. Do you agree with this view? What should the EU be doing?

Hayton: The most important thing that the EU and its member states can do is turn up and take an interest. Demonstrating presence and commitment helps to bolster the resolve of those countries in Southeast Asia currently facing Chinese coercion. Naval visits and diplomatic exchanges, along with international communiqués that remind the world of the EU’s interests and position are all helpful.

Those EU member states with the capabilities, should play their part in upholding the international rules on freedom of navigation. China’s actions in the South China Sea demonstrate that it regards freedom of navigation as something that it can obstruct at will, rather than an international principle to be upheld at all time. The only way to prevent the rules from collapsing is to make use of them.

The EU and its member states now need to seriously consider taking action to uphold other principles as well. UNCLOS and its EEZ regime are cornerstones of international law. The EU needs to make clear that it supports the right of coastal countries to control the resources in their own EEZ. The EU should take a view on what is, and is not, a legitimate claim to maritime resources and then orientate its policies accordingly.

While the deployment of naval ships gets a lot of attention, there are many other ways that the EU could help to protect the EEZ regime. It could require importers of fish, hydrocarbons or other marine products into the EU to prove that they were extracted legitimately. It could sanction companies and officials who violate other countries’ EEZs by poaching fish or by drilling or exploring for oil and gas. It could use the power of satellites and other remote sensing systems to ‘name and shame’ violators. It can provide aid to coastguards and also help coastal states improve their maritime domain awareness.

It could also think about deploying assets to defend the EEZ regime. Where a country, such as Vietnam or Malaysia is engaged in a legitimate activity within its legitimate EEZ, the EU could post a coastguard or naval vessel to observe and publicize violations of international law. The ultimate step would be to intervene to prevent such violations but I think that we are some way from that. At the moment the EU should use its reputation as a rule-builder to encourage the spread of good behaviour and sanction examples of bad behaviour.

Now that the Philippines has won a binding ruling on the subject the EU has a clear point of principle to defend. If other claimant states could obtain similar rulings it would help the EU to defend their positions too.

________________________________

Dr. Felix Heiduk, Asia Associate for German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP)

Echowall: On August 5, Federica Mogherini, the EU's foreign policy chief said during a visit to Hanoi that "increasing tension" in the South China Sea was a concern for the EU. I wonder if you could start by summarizing your take for European readers of the situation. What has been happening in the South China Sea, and why are China's sovereignty claims there of concern to Europe?

Heiduk: EU representatives, as well as representatives of its member states, have repeatedly stated that the EU has a major interest in a stable, peaceful South China Sea. I would argue the drivers here are primarily economic. Most of Europe’s trade with Asia transits through the South China Sea. China and the ASEAN states are, respectively, the EU’s second and third largest trading partners. In its Maritime Security Strategy, the EU warns that as much as €4.74 trillion per year in maritime trade could be affected by an outbreak of armed conflict in the South China Sea. More generally, with economic interdependence between Europe and Asia increasing, the importance of a stable, prospering Asia for Europe’s economic security is set to grow further in the coming years. In particular, the sea-lanes running from the Straits of Malacca through the South China Sea to East Asia are deemed vital for the EU’s trade with its partners in Asia.

Secondly, the primacy of economic interests in the region does not negate a security dimension. As any disruption of the maritime trade with Asia, via the outbreak of a military conflict, via a military blockade of chokepoints or via other coercive measures would have a significant short-term negative impact on Europe’s economic well-being, the stability and security in the region is closely intertwined with Europe’s economic security.

Various European observers have highlighted the negative impact that an outbreak of military conflict in or around the South China Sea would have on the global economy. The interlinkages between the EU’s economic well-being as predominantly a trading power and stability and security in Asia are clearly accentuated in the EU’s Global Strategy. The Global Strategy says, “There is a direct connection between European prosperity and Asian security. In light of the economic weight that Asia represents for the EU – and vice versa – peace and stability in Asia are seen as a prerequisite for the EU’s economic prosperity.”

Thirdly, the EU has declared an interest in preserving what it commonly refers to as the “rules-based international system,” specifically the international law of the sea. The EU’s self-image as a “force for good” and a “normative power” in international politics are reflected in many of its principled statements on the South China Sea. While not taking a position on claims to land territory and maritime space in the South China Sea, the EU urged all claimants to resolve disputes through peaceful means, to clarify the basis of their claims, and to pursue them in accordance with international law including UNCLOS and its arbitration procedures. EU strategic documents and policy papers have therefore stressed the importance of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea and encouraged the parties to peacefully resolve disputes in accordance with international law, particularly the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Echowall: One EU official mentioned in the context of the EU-Vietnam agreement the importance of "safeguarding the rules-based multilateral order." Based on its actions in the South China Sea and globally and its public statements, what can we say about how China regards the international rules of the sea?

Heiduk: I would argue that China’s outlook on UNCLOS is rather different from the EU’s principled view. The example Bill Hayton cited about Zhou Bo is just one of many that illustrate the point that UNCLOS is very much “re-interpreted” by Beijing in line with what it perceives to be its “national interests.” At the same time, many in the U.S. government consider involvement in international organizations and treaties such as UNCLOS to be detrimental to U.S. national interests, too. As a result, the U.S. has not even ratified UNCLOS. From the view of small and middle powers, the increasingly adversarial attitude of Beijing (and Washington) to international law and the rules-based international order is therefore, perhaps unsurprisingly, problematic to put it mildly.

However, what one can observe is that the EU has shown little activity, beyond principled statements, to safeguard the rules-based order in the South China Sea. In my view, the EU and its member states have painstakingly avoided taking sides in the South China Sea disputes and have refrained from any clear positioning. This prism has remained unchanged for quite some time and is stipulated in key strategic documents published by Brussels, such as for example the 2012 “Guidelines on the EU’s Foreign and Security Policy in East Asia” or the EU’s 2016 “Global Strategy.”

The EU has employed this approach in response to major developments in the South China Sea, such as the 2014 “Oil rig incident” when China deployed an oil rig in disputed waters, resulting in clashes between Chinese and Vietnamese boats, the 2016 SCS Award on the so-called South China Sea arbitration case, or the recent quarrels between Hanoi and Beijing. I would argue that the EU and the majority of its member states are still searching for some sort of sweet spot between Washington and Beijing, which I would argue simply doesn’t exist anymore – if it ever did.

Guided missile destroyer USS Howard (DDG-83) in rough waters in the South China Sea in 2004. Public Domain image by US Navy posted at Wikimedia Commons.