The Stanari power plant in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Photo by Ning Hui.

Coal at a Crossroads in the Balkans

Even as a consensus has emerged that coal must be phased out, Chinese investment is empowering the growth of coal power across the globe. At the crossroads of this debate in Europe is a series of new coal power projects in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In the town of Stanari, in the northern hills of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Chinese came and the Chinese went. Jerimic M. Eoran, 43, a local coal miner whose family has worked in the open pit lignite mine here for three generations, recalls lignite mining in the area slowing progressively through the years. By 2004, operations had nearly come to a complete stop.

All that changed in 2012 with the arrival of the Chinese construction and engineering crews. That year, work began on the building of the brand new 300 MW Stanari thermal power plant, or TPP Stanari.

Key Points:

* In 2016, construction was completed for Bosnia-Herzegovina’s first new coal-fired power plant in decades, made possible by Chinese financing. Five other coal power projects in the country are in planning with Chinese financing.

* Given Bosnia-Herzegovina’s lagging economy and lack of jobs, employment positions at state-owned mines and power plants is highly prized for those with political connections. Local politicians tend to use such projects as political capital.

* A loan guarantee for one Chinese-financed coal project, Tuzla 7, could constitute illegal state aid under EU rules. This and other concerns regarding state aid, public procurement and environmental impact could cause problems for Bosnia-Herzegovina’s bid for EU membership.

Coal’s new lease on life in Stanari began in 2005, as Energy Financing Team (EFT), a London-based company founded by Serbian businessman Vuk Hamovic, took over control of the mine and announced plans to build a coal power plant. China Development Bank stepped in to extend a 350 billion Euro loan, and Dongfang Electric, a Chinese company headquartered in Sichuan province, won the bid for construction of the plant. A contract was signed in late 2012, and the Chinese arrived on site soon after.

Eoran remembers hundreds, sometimes thousands, of Chinese workers camped near the building site. Through faltering interactions, he managed to pick up odd details about Chinese life and culture. “It turns out that all Chinese names have special meanings,” he explains. But the detail that made the most lasting impression was a story he didn’t dare pursue further. “One Chinese worker received news that his father had died,” he tells me. “He wanted to go home and attend the funeral, but the boss wouldn’t allow it, so he committed suicide. He hanged himself.”

This rumor, which spread among the local miners in Stanari at the time, is Eoran’s strongest lingering impression of the Chinese. Once construction was completed in 2016, the Chinese workers packed up and left. For a while, a few engineers remained to ensure that the EFT team could operate the plant smoothly. But even the engineers are gone now.

Fighting the Phase Out

Before the Stanari plant went up, a new coal plant had not been built in Bosnia for decades. The country did not lack for generation capacity, and in fact has for years exported electricity to neighboring markets, including Croatia and Montenegro. But its four state-owned power stations, with an average running period of 40 years, were all seriously aging.

The open pit lignite mine in Stanari, which supplies fuel for TPP Stanari. Photo by Ning Hui.

Few question that Bosnia-Herzegovina’s power infrastructure is urgently in need of upgrading. But the reliance on coal, experts and environmentalists say, means turning back to the past at a time when more action is needed to face the challenges of environmental pollution, climate change, and sustainable economic development.

Climate scientists are in agreement that the best way to mitigate the most serious effects of climate change is to move toward renewable sources of energy and away from coal and other fossil fuels. Phasing out the use of lignite – one of the dirtiest and most carbon intensive forms of power generation –has been cited as a particular priority.

Reliance on coal, experts and environmentalists say, means turning back to the past at a time when more action is needed to face the challenges of environmental pollution, climate change, and sustainable economic development.

Given the clear trend away from coal and toward renewables, more and more financial institutions have divested from thermal coal. The World Bank announced in 2013 that it would stop supporting coal projects, and as of February 2019, more than 100 financial institutions globally, including 40 percent of the world’s top 40 banks and 20 insurance companies had divested themselves. The European Investment Bank announced last month that it would stop funding fossil fuel projects by the end of 2021.

For all of these reasons, Bosnia-Herzegovina, which still relies on coal for roughly 60 percent of its electricity generation, has fewer and fewer opportunities available to attract loans or investment from the West for the construction of new coal power capacity.

There are opportunities, however, in the East, where China has shown itself willing to support new projects, both in financing and construction.

Building Capacity

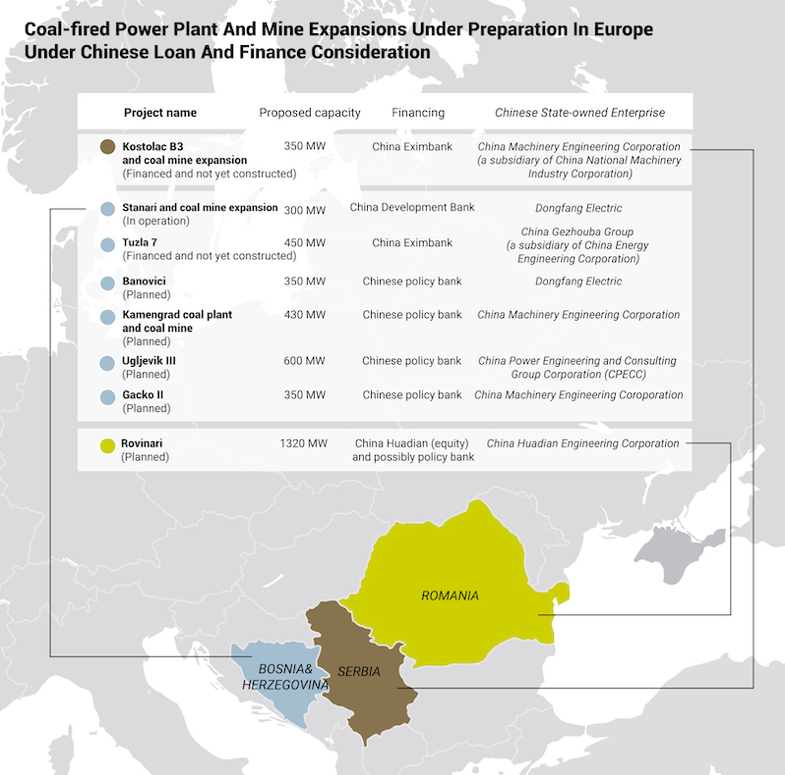

When it comes to China’s financing and construction power in Bosnia’s coal power sector, Stanari is just the beginning. Aside from Stanari, five other coal power projects in the country could accept financing from China. These include the Tuzla 7 lignite power plant, a brand new 450 MW unit that is to be added to the Tuzla Thermal Power Plant, the largest thermal power station in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Coal projects in the Balkans with Chinese involvement. Graphic by Alice Tse. Data source: Wawa Wang.

The Tuzla 7 project has an estimated total investment of 901.3 million euros, of which nearly 614 million will come from loans from the Export-Import Bank of China, a state-funded and state-owned policy bank directly under China's State Council. The project is to be built and operated by two companies, China Gezhouba Group, under the central state-owned enterprise China Energy Engineering Group, and Guangdong Electric Power Design Institute, a subsidiary of the state-run China Southern Power Grid.

Tuzla, located roughly 80 kilometers from Stanari in the northeastern corner of Bosnia and Herzegovina, has long been the industrial heartland of the country. Unlike TPP Stanari , the Tuzla Thermal Power Plant is a state-run project, operated by Elektroprivreda Bosne i Hercegovine (EPBiH), sometimes referred to as Elektroprivreda BiH. Its six units currently burn an estimated 330,000 tons of lignite each year.

To the tens of thousands of residents living in towns and villages near the plant, the chimneys rising from the power plant, erected back in the 1960s, have often been a source of contention.

Senad Isakovic Roko, a 50-year-old army veteran who has opened a pet grooming shop in the village of Šićki, close to the Tuzla plant, places a compliant white Pekinese onto his worktable as he gestures off in the direction of the plant, a razor in his hand. “I can see the power plant from the window in my house,” he says, starting to shave the dog. “But central heating from the plant has never been made available to me.”

Senad Isakovic Roko, a 50-year-old army veteran who has opened a pet grooming shop in the village of Šićki, has been a leading activist against the Tuzla Thermal Power Plant. Photo by Ning Hui.