Image generated by DALL-E AI system.

China’s AI: Sputnik Scare or iPhone Spark?

As large AI models proliferate, Chinese developers are caught between the risk of layoffs and the challenges of starting their own businesses

Quick Takes:

- International analysts frequently frame China’s AI progress as a U.S.-China power rivalry, overlooking the internal market forces and talent dynamics driving its rise.

- Unlike the mobile internet boom, which fueled a startup golden age, the AI boom is constrained by high infrastructure costs, limited monetization, and intense regulation.

- Despite technological breakthroughs, profitability remains elusive, and most Chinese AI firms are locked in a fierce price war to claim market dominance.

- Chinese programmers face a harsh paradox—layoffs loom as AI automates coding, while firms prioritize young, competition-tested talent, pushing many toward precarious self-employment.

- Aiming to “go abroad” to escape domestic competition, Chinese AI developers often underestimate the geopolitical risks and regulatory hurdles that come with it.

Editor’s Note

This article took shape through extensive dialogue between Echowall and the author, Mr. Chang Zheng, a veteran in China’s artificial intelligence (AI) sector. While outside observers rarely have direct access to Chinese industry insiders’ perspectives on the domestic factors driving AI’s rapid growth, we are deeply grateful to the author for his candid sharing.

AI is now seen as a global battleground, but while international analysts frequently cast their eyes upon China, they tend to parse the topic in terms of a great power competition. In January 2025, Chinese AI startup DeepSeek made global headlines with its low-cost, open-source AI model. The company claimed to have developed the model with significantly lower funding and computing resources than its American counterparts, sparking international debate and sending shockwaves through U.S. stock markets.

Analysts have dubbed this moment the “AI Sputnik Moment,” comparing it to the Soviet Union’s 1957 satellite launch, which spurred the United States into an all-out space race. This analogy, rooted in geopolitical concerns, underscores anxieties in the U.S. regarding whether its current strategies are sufficient to preserve a technological edge over China.

However, it is important to recognize that the development of artificial intelligence ultimately relies on human ingenuity. In academic research, discussions about AI’s disruptive impact on human work mainly focus on two levels: at the macro level, examining shifts in labor markets—such as job displacement or creation—and at the micro level, exposing the exploitation of outsourced data workers by the AI industry.

This essay elaborates how China’s programmer community, caught in intense competition, is often forced into self-exploitation, navigating a ruthless, dog-eat-dog tech arena. ChatGPT’s breakthrough in large-model development sparked visions of opportunity, with some foreseeing a golden era for Chinese startups —akin to the boom a decade ago when the iPhone dominated the market. However, they soon faced a harsh reality: a suffocating tech arms race, waves of layoffs, and limited market opportunities for entrepreneurs. While many see “going abroad” (selling software and services to foreign buyers) as a crucial survival strategy, we have noticed that these Chinese tech professionals often lack a deep understanding of the profound geopolitical uncertainties that come with it.

China and the ‘iPhone Moment’

When U.S.-based OpenAI launched its AI-powered chatbot, ChatGPT, in November 2022, it reached 100 million daily active users within just two months—a milestone that took Twitter five years and WhatsApp 3.5 years to achieve. ChatGPT heralded the age of a new digital economy driven by a new tech paradigm, with all the attendant opportunities. This prompted Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang to describe the moment as AI’s “iPhone moment”—a reference to the disruptive impact of Apple’s iPhone and App Store around 2010, which catalyzed a boom in the mobile internet sector. This transformation created significant profit potential while driving consumer usage costs toward zero by converting the marginal cost of producing and accessing information into a fixed cost. For example, print maps of the USA used to cost $3, but nowadays Google Maps is available for free.

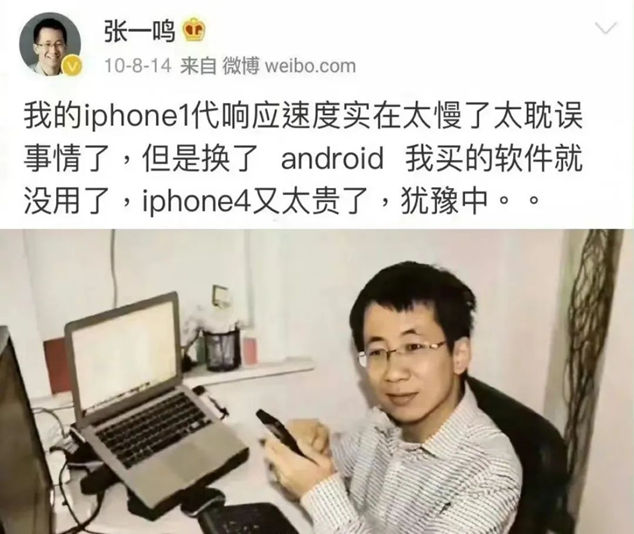

Following this “iPhone moment,” there was a flurry of Chinese startups, and many stories of grassroots founders making it big. A 2010 Sina Weibo screenshot, which remains viral in the developer community, captures an early-stage entrepreneur lamenting his inability to afford the new iPhone 4. That same entrepreneur has since been hailed by the media as China’s most likely candidate to become the world’s richest person.

Screenshot of a 2010 Sina Weibo post by Zhang Yiming. The text reads: “My first-gen iPhone responds really slowly – things just take too long – but if I switch to Android, the software I bought before will be unusable. On the other hand, the iPhone 4 is too pricey, so I’m hesitating.”

We are talking about Zhang Yiming, who founded ByteDance in Beijing in 2012 with an initial capital of $300,000. He developed the news aggregation app Jinri Toutiao (“Today’s Headlines”), which used algorithms to curate and distribute personalized news, stories, and images. The app’s revenue model was based on advertising, with Zhang emphasizing the power of recommendation algorithms in precisely matching ads to potential customers. Although the app faced significant controversy over copyright and privacy issues, it surpassed one billion users by 2024. ByteDance is now valued at $268 billion, with its internationally renowned short-video platform, TikTok, having become one of the world’s most popular—and controversial—social media apps.

“Custom automatic recommendations” are seen as ByteDance’s technological special sauce: The company capitalized on the entrepreneurial opportunities created by the iPhone era, which significantly lowered consumer adoption costs, enabling ByteDance to rise as China’s newest internet giant. Zhang Yiming’s career is a clear example of an “iPhone moment” paving the way for Chinese grassroots entrepreneurs.

The Large AI Model Arms Race

Unlike the 2010 iPhone moment, which reduced costs on the ‘demand side’, large AI models have accelerated productivity gains on the ‘supply side’, so to speak.

An example from professional translation: this author spoke to a translator friend who uses Kimi Intelligent Assistant (developed by the Chinese company Moonshot AI) for drug regulatory translations. This tool allows him to complete every 1000 Chinese characters of text in less than 3 minutes, compared to the hour or longer that conventional human translation would take.

However, AI products like this primarily serve businesses rather than end consumers, limiting the size of the paying market. Monetizing AI remains a global challenge for the industry. Additionally, while the infrastructure for mobile internet was already consumer-ready when the ‘iPhone moment’ arrived, AI service providers today grapple with high infrastructure costs, including expensive chips and cloud computing.

The motivation for the ‘large model arms race’ is the desire for a dominant technological position and/or an oligopoly status that will secure long-term capital returns.

At the core of the current AI business and tech application ecosystem are large models, supplying intelligent operations and services akin to water or electricity. The motivation for the ‘large model arms race’ is the desire for a dominant technological position and/or an oligopoly status that will secure long-term capital returns.

In both China and the US, the large model race is propped up by investors, businesses, and government support. As for government involvement, a Chinese New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan was laid down back in 2017 with a clear goal of reaping spin-off effects from new-generation AI to the tune of 10 trillion yuan. Chinese government venture capital backed 9,623 individual companies from 2000 to 2023 with a total of $184 billion. By July 2024, over 300 large AI models were online in the country. Financing for large AI models exceeded 30 billion yuan in the first half of 2024. This led to the rise of various tech unicorns focused on such models, each valued at over US$1 billion, with the best-known earning the collective moniker of "the six tigers" (Zhipu, Baichuan, 01.AI, Moonshot AI, Minimax, and Stepfun).

The arms race is, admittedly, global in scale. By early July 2024, there were 1,328 large AI models worldwide (including different parameter variants of the same model from the same company). The US led with 44% of these models, followed by China with 36%.

Under the paradigm of nationalist techno-determinism, U.S. government support for AI is primarily focused on maintaining the country’s technological edge, particularly in relation to China. In October 2022, a series of export controls were imposed on China, restricting its access to advanced chips and cloud services needed for training large AI models. The ENFORCE Act (Enhancing National Frameworks for Overseas Critical Exports Act), introduced in May 2024, targeted restrictions on large model exports to China. In November 2024, the US launched a major AI initiative, dubbed a ‘Manhattan Project’ for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), to outpace China. A month later, the Commerce Department added 140 Chinese firms to the Entity List, curbing tech exports. The emergence of DeepSeek will undoubtedly prompt the United States to impose even stricter technological restrictions on China’s AI development.

The most fundamental difference between the US and Chinese drives to build large models is that the former is a leader, the latter a chaser. With Washington imposing a series of “throttling” measures on Chinese AI development, open-source software has become a strategic priority for both Chinese businesses and government efforts. Globally, significant debate persists regarding the definition of open-source AI and the motivations behind AI firms adopting this approach. Simply put, by making their large models open-source, AI companies aim to establish them as industry standards, fostering long-term adoption and dependence within their ecosystems. Before DeepSeek, Meta had solidified its leading position in the open-source AI landscape.

From China’s policymaking perspective, open-source models help drive indigenous innovation and make it easier to control AI applications and ensure security. For Chinese businesses, they offer a low-cost pathway to accelerate the development of their own technological ecosystems. While most large-model players in China have not publicly detailed the origins of their technology, the consensus view among insiders is that OpenAI, Meta, and Google’s models are the primary international open-source references from which they are learning.

In July 2024, the Hangzhou city government announced its commitment to developing a high-quality, full-industry AI value chain, emphasizing the importance of building an open-source large-model ecosystem. Notably, Hangzhou is the birthplace of DeepSeek (launched in 2023). DeepSeek adopted one of the most permissive open-source licenses—the MIT License, which imposes no restrictions on downstream applications.

DeepSeek’s rise reinforces China’s confidence in an open-source AI strategy. At the same time, U.S. AI industry leaders, including Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg, emphasize the geopolitical stakes in AI development. “There’s going to be an open-source standard globally, and I think that for our own national advantage, it’s important that it’s an American standard,” Zuckerberg said.

Meanwhile, DeepSeek inspires cost-effective AI growth elsewhere: For Europe, researcher Lucie Aimée Kaffee sees a high potential to excel in “efficiency and responsible AI” with such models, while India plans to deploy DeepSeek models on domestic servers. Looking ahead, the global AI race will likely be defined by a geopolitical battle between open-source and closed-source models. Chinese entrepreneurs and developers are poised to play a pivotal role in shaping this future.

Homogeneous Approach and Price War

DeepSeek’s sudden rise has prompted the U.S. tech community to rethink the “Bigger-is-Better” paradigm in AI. Critics argue that tech giants’ relentless pursuit of ever-larger models has stifled innovation and diversity of approach. However, it is fair to say that China’s own "AI arms race" has similarly led to product homogenization.

Testing by the media in October 2023 showed that China’s leading AI models were nearly indistinguishable, with almost identical interfaces, functionalities, and usage methods. Similar dialog boxes, performance scores, and browser and app-based access left users struggling to differentiate between models—aside from the logos. Industry insiders say that China’s prevalent large models rely on similar tech architecture and algorithms and are trained on public data; the competitive pressure to release a product leads AI players to go for market-proven service models.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman predicted in 2024, "There are clearly tons of large language models being trained. I would guess that only a small number—10 to 20—will attract the majority of users and resources." Many industry experts believe China’s AI sector will follow a ‘winner-takes-all’ trajectory, much like the 2010 "battle of the group buyers" back in the ‘iPhone moment’ days of the mobile internet. Group-buying platforms allow consumers to pool their orders to secure discounted prices, making this e-commerce model highly popular for cost-saving and social shopping. At its peak, China had over 5,000 group-buying platforms, but only a few survived, led by Meituan, which later grew into a major tech giant. Today’s "battle of the models" is unfolding in a similar way—this time through aggressive price wars.

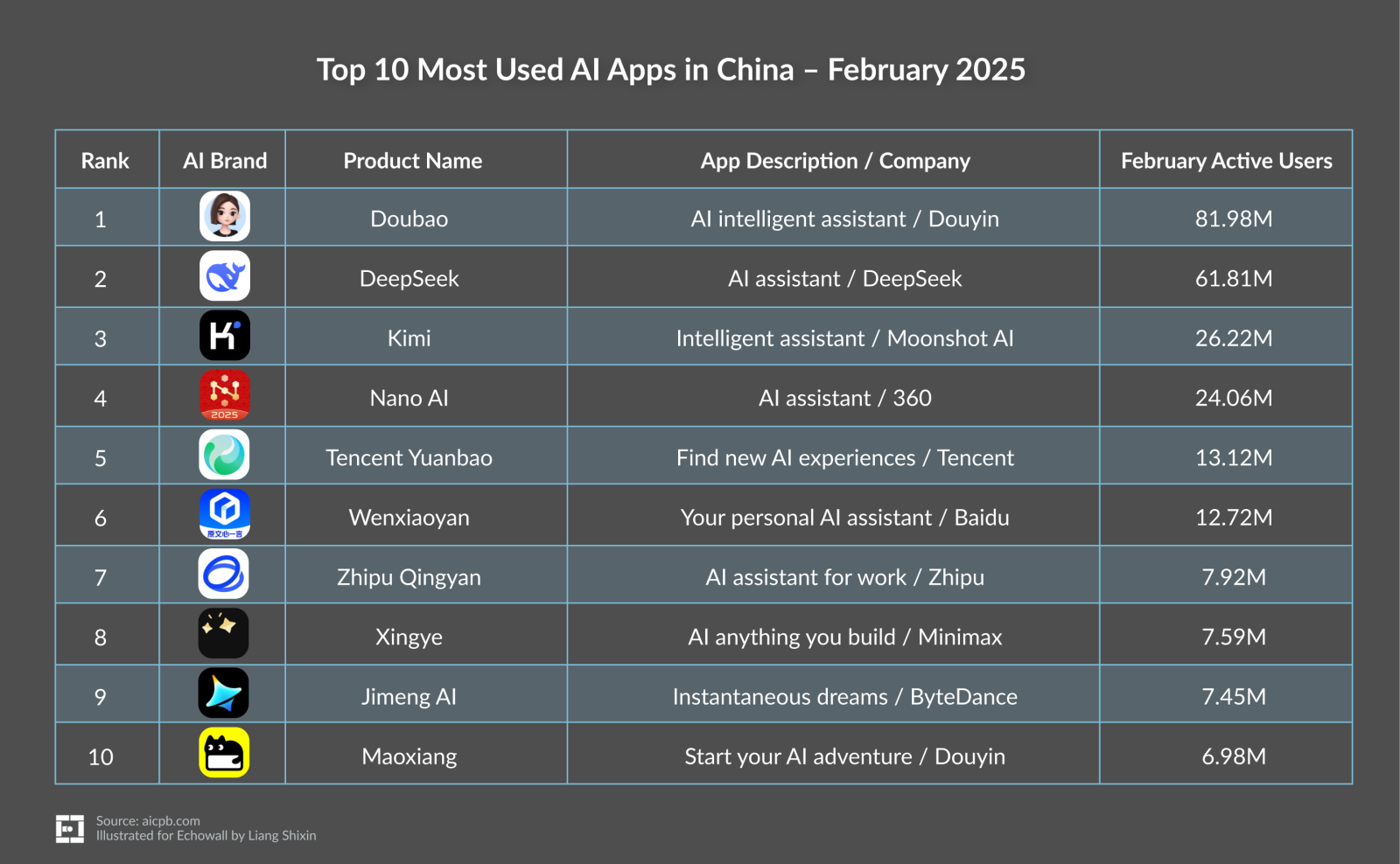

In May 2024, DeepSeek slashed the cost of its DeepSeek-V2 model, pricing it 100 times cheaper per million tokens than GPT-4 Turbo at the time. Due to its relentless focus on low costs, DeepSeek earned the nickname "the Temu of large models" in China’s AI community. In the same month, ByteDance’s Doubao model further escalated the price war, cutting its prices to just 0.7% of the industry average, triggering a wave of similar price reductions.

The brutal price war underscores both the intense technological and talent rivalry within China’s AI industry and the struggles of AI firms to recoup their massive investments.

This brutal price war has become completely detached from actual costs; instead, AI companies are racing to undercut competitors, capture market share, and ultimately achieve a winner-takes-all dominance. The battle underscores both the intense technological and talent rivalry within China’s AI industry and the struggles of AI firms to recoup their massive investments. While "the six tigers" are attempting to differentiate their services, no stand-alone large model provider has yet turned a profit or even reached a break-even point.

Popular Anxiety Amidst a Stream of Tech Breakthroughs

The AI large model fever is driven by a conviction not only in China’s tech sector, but also in public opinion at large that technology can change lives. But this popular conviction is morphing into anxiety, as evidenced by public reactions to AI news and individual responses to AI itself.

Long before the arrival of ChatGPT, AI garnered intense media interest, particularly from platforms like Jiqi Zhixin, QbitAI, and AI Era, which focus on AI movers and shakers for their million-plus readers. A look at their daily output will turn up headlines all emphasizing technological revolution and containing buzzwords such as “first-ever”, “best”, “transcending” and “new breakthrough”. At first glance this reflects vibrancy in the tech and AI scenes; however, when inundated daily with hyperbolic headlines about how ‘technology is being disrupted again and again’ and shown their potential competitors or leapfroggers reaching new milestones, industry insiders cannot help but feel enormous stress. This creates an odd discord: the more ‘positive’ the news spin, the more ‘negative’ and stressed the readers feel.

Since ChatGPT, AI has moved from being a specialist area to a topic of general interest. The public’s preference for information in short video form has led to a proliferation of AI social media, led by video blogger Li Yizhou, whose AI Course for Everyone sold 250,000 subscriptions worth 50 million yuan from January 2023 onwards. The joke goes that when it comes to promoting AI to the public, Li Yizhou is the only person in China who can rank up there with Sam Altman. Li Yizhou’s typical sales tactic is to claim “there are only 6 places left” while in reality, a place is always available as long as you can pay. Li’s rise to stardom is a sign of the pervasiveness of popular anxiety about AI driving continuous change and having disruptive effects.

Screenshot: Li Yizhou, AI class, with Li claiming that AI is becoming more and more ‘human’