Chinese workers wearing yellow safety helmet. Image by Pixabay available at Pexels.com under CC license.

Beyond CAI – Why China’s Labor Rights Matter

For the EU, improving China’s labor standards and protecting the economic and social rights of Chinese workers is not only a moral responsibility but a long-term benefit as well.

Quick Take

- China’s exploitative labor system can be viewed as government subsidies in disguise for Chinese and multinational corporations operating in China.

- European companies have never been motivated to change the existing exploitative labor regime. However, as recent examples have shown, China’s labor rights became a global economic, social and political issue.

- For the EU, pushing for China’s ratification and implementation of the ILO’s core conventions and protecting the economic and social rights of Chinese workers is not only a moral responsibility but a long-term benefit as well.

In May 2021, a US court awarded $5.4 million to seven Chinese workers in compensation for forced labor, human trafficking and workplace injuries at a construction site in Saipan. The company that lost the lawsuit is based in Hong Kong and owned by Mainland China.

For Chinese workers, this rare victory highlights a different perspective when we’re trying to understand China’s labor rights. So far, whether we’re talking about the China-EU Investment Agreement or Germany’s recent Industrial Chain Law, the European Union’s focus on China’s labor rights violations has recently only been highlighted because human rights organizations have pointed to the forced labor of the Uighurs in Xinjiang in the ‘re-education camps’. However, it still fundamentally ignores the exploitative labor system all over China, which has long been the institutional basis for international companies to over-rely on China’s supply chain. With the labor system’s low cost, China has a large-scale comparative advantage, and they are already a main player in the global production network. But the consequence of the lack of basic workers’ rights is that the standard China labor model challenges pre-existing international labor standards.

As a member of the International Labor Organization, China has yet to sign the four core labor conventions, which have to do with forced labor (29, 105) and association and collective bargaining (78, 98), especially because China has always viewed the independent organization of workers as one of the biggest threats to its political survival. Therefore, the International Labor Organization has no way of pushing China to approve of these four core values in order to guarantee labor rights. The writer of this article once overheard an ex-International Labor Organization official in Geneva say that they no longer expect to change China’s mind when it comes to labor, and that they only hoped that China wouldn’t change the International Labor Organization. They furthermore added that all signs point to the weakening influence of the Geneva headquarters on Beijing. For this reason, at least in Europe, emphasis is made on Chinese labor rights when it comes to trade agreements, as the EU is trying to establish a system of workable supervision and verification mechanisms.

This article aims to argue - on three levels - why European society should proactively advance China’s signing of the core values of the International Labor Organization: from the perspective of the specific characteristics of China’s system of labor exploitation, new developments and China’s exportation overseas.

Labor Exploitation with Chinese Characteristics

The enormous market in China is hugely attractive to European enterprises. Volkswagen Group’s businesses in China are a perfect example. Its factory in Urumqi, Xinjiang, has lately come into question in the eyes of the Western public. Volkswagen’s response to this was to say that every single one of the Volkswagen employees in Xinjiang has directly signed a labor contract, and therefore they believe there is no such thing as a phenomenon of forced labor.

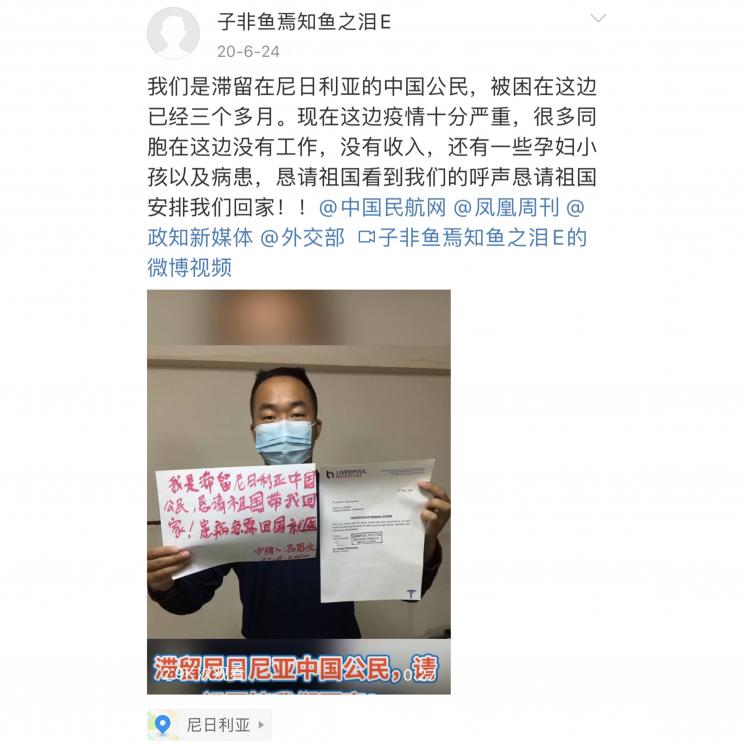

Screenshot of a Weibo post by a Changchun Volkswagen’s worker on May 16, 1997, shows pictures of protests and dissatisfaction with the handling of relevant departments such as labor union, the court and the goverment.

No matter the specific situation in this factory, it is fair to say that there are labor issues when it comes to Volkswagen in China. Like many other international automobile enterprises, Volkswagen uses ‘labor force dualism’ by hiring both formal contract workers and agency workers side by side on production lines in order to cut labor costs.

The dispatch workers do the same assembly work as formal workers, but make half the income, with none of the similar benefits. For many years in the Volkswagen factory in Changchun, China’s labor law contract has been violated with different pay for equal work. Finally, in 2016 and 2017, thousands of dispatch workers protested to defend their rights, causing the arrest and sentencing of the protest leaders. Volkswagen was then pressured to sign official contracts with some of its dispatch workers, but workers’ demands for compensation for their wages were not fulfilled.

Screenshot of the DW report on the protest held by the Chinese workers from the Volkswagen factory in Changchun on March 3, 2017.

Aside from this, most of the suppliers that provide various accessories for large multinational car companies are local, private companies, which means they have even lower labor and environmental standards. Therefore, it can be argued that over the last thirty years, a multinational company like Volkswagen benefited immensely from China’s labor regime, and at its core still has exploited cheap migrant workers economically, socially and politically. This is also the systematic driving force behind China’s market reforms that have created the economic miracle, which Chinese economists have called their ‘comparative advantage’, though a more precise way of saying is its “low human rights advantage”(低人权优势)as historian Qin Hui has pointed out. According to data from 2020, there are 285.6 million migrant workers in China who form the main body of industrial workers and are mostly spread out in manufacturing, the construction industry and the service industry. This article will focus on migrant laborers in labor intensive industries and will talk about how they have been exploited in delate.

A Quasi-Militarized Regime for Production

First of all, economic exploitation is embedded in the labor process where migrant workers’ wages have been intentionally suppressed in the long term. In practice, the minimum wage set by the local government has become the basic wages for workers (five days a week, eight hours a day). The salary doesn’t even cover the basic necessities of life, so workers have to agree to work over-time. For example, workers worked more than 100 hours per month on average at Foxconn, where in 2010 there were a string of suicides. For migrant workers, they were doing overwork ‘voluntarily’ but this was actually without a choice, because they have to make more money in order to live. In order to get around the bounds of the labor laws, the factory demands its workers to sign a Voluntary Overtime Contract.

Also, to ensure maximum efficiency during production, Chinese factories carry out a militaristic factory dictatorship with strict discipline, loud scolding and the widespread use of fines at the core of this dictatorship. With these management methods, not only does it force migrant workers to work tirelessly on the production line, but they must also suffer through long periods of mental distress. Aside from the itemized nature of the production workshop and the isolation and compartmentalization of the migrant workers’ living quarters, the workers themselves come from different production workshops. These have different day and night shifts, so there is extreme transience where the workers do not know each other, even though they are sharing the same room. This means they are unable to form a supportive social network. This kind of factory regime is the root of what caused the streak of Foxconn migrant worker suicides. But what’s worse is that labor standards at Foxconn are actually the best compared to other factories, and the OEM companies that have become popular recently have made the migrant workers’ conditions even worse. For example, it is now harder for them to get an official labor contract, as well as pay into social insurance, which means they can only work as an outsourced worker. Even though the phenomenon of labor shortage has occurred in some areas, and some factories raised wages for some short-term contracts. However, the high pressure, high dictatorship and exploitative situation hadn’t changed in the slightest.

Foxconn workers. Image by iphonedigital available at Flickr.com under CC license.

The Collusion of Government and Capital

Enterprises achieve their growth in profits from low costs, easily tamed and efficient migrant workers, and more so they are the pillars for China’s transformation into the ‘factory of the world’. This is significant because together with capital, the Chinese government has created an exploitative system for labor workers that is beneficial to both parties, and the main ‘contribution’ from the policy aspect is social and political exploitation.

Social exploitation manifests as a split labor reproduction mode, which means the State has constructed, through the household registration system, a dual labor market based on the urban and rural divide, so that the household registration for migrants state ‘peasants’, whereas their occupation is industrial worker. This separating of their identity and occupation means their wages in the city can merely maintain the costs of their own labor reproduction. They don’t have an urban household registration, only a temporary residence permit, and they will go back to their villages after they get old or retire, but their children have to stay and be educated in the village, and therefore the companies do not need to make payments towards their retirement, housing, their children’s education, medical bills, skills training and other social benefits. This is the fundamental reason that China has been able to maintain low long-term labor costs.

For the migrant workers, this system sets them up for double-exploitation: on the one hand the traditional political and economic exploitation of the factory owner and the laborer and the exploitation of the laboring class, and on the other hand the State purposefully creating a separation in identity, where the civil and social rights for migrant workers are being deprived. Because there are serious problems with unbalanced distribution between the city and the countryside, public services and social benefits for migrant workers remain low.

The political exploitation is manifested as the government’s, at all levels, prioritization of economic development. The first Chinese Labor Law was unveiled in 1995, and the Labor Contract Law was introduced in 2008. Yet, in reality, justice and law enforcement agencies often pretend they are oblivious to these acts of labor exploitation. For example, in instances where Volkswagen employees took their cases to a local court, their cases were not upheld, yet local police quickly apprehended the leader of the workers. Furthermore, in May of this year, the Standing Committee of the Shenzhen People’s Congress revised the “Regulation on Paying Wages”, which openly went against the Labor Law, deleting the regulation that stipulates triple-pay on statutory holidays, while adjusting the period for revising the minimum wage standard from every two years to every three years.

Migrant workers, particularly the first generation, have a low level of education and are without knowledge about labor laws and arbitration, therefore it is hard for them to protect their interests through a long and complicated legal process. In the last dozen years or so, faced with low wages and poor working conditions, a new generation of migrant workers who have entered the factory have started to resist the conditions with large-scale strikes one after the other. And on the other hand, learning from the example of the Polish Solidarity Movement, the State has absolutely banned migrant workers from forming trade unions or to fight for their rights using strikes. At the same time, the State severely attacks NGOs which voluntarily provide legal aid and social services for migrant workers. For example, National Security workers often follow as well as talk to NGO workers, shut down the space where NGOs operate, or even detain and sentence the people who provide supportive strategies for strikes. Under these circumstances, where there is lax enforcement, with high political pressures, migrant workers often have to resort to extreme methods such as suicide, self-immolation, seeking revenge or the help of the mafia when they are owed salaries, denied social insurance, or have work-related injuries and occupational diseases.

In recent years, migrant workers have become less interested in traditional manufacturing work and have instead started to focus on service jobs such as housekeeping, driving, and food delivery. The assembly line for these jobs are, comparatively speaking, more flexible, but the characteristic exploitation has not changed. For example, most of the work for internet platforms is outsourced, and no clear labor contract are signed with the migrant workers, not to mention social security, and the Labour Law and the Social Insurance Law cannot give them systematic protection. Workers still have to use extreme methods when in the middle of a labor dispute, such as riots or self-immolation.

In order to get used to this structural change in the labor market, the Chinese manufacturing sector is experiencing the spatial fix that Silver talks about in Forces of Labor, as well as the technological fix and the product fix.

Race to the Bottom

As mentioned above, a basic advantage that China has in being able to compete internationally is due to a supply of hundreds of millions of migrant workers who act as cheap labor. General speaking, China still relies on developing labor-intensive industries, and takes a fundamental role for manufacturing and production, in order to advance the fast pace of economic development. It’s obvious that this Chinese growth is actually a continuation of the ‘East Asian Miracle’. As the historical experience of Japan, Korea and Taiwan shows, with the arrival of the Lewis turning point, the supply and demand relationship in the labor market will change, and the ‘world factory’ method of development will be hard to sustain, which means the industrial structure will require adjustment.

At present the Chinese economy is experiencing this process. Since 2011, the working population of ages 15-59 has begun to grow negatively, which means that China’s demographic dividend has begun to disappear, and the labor force no longer has this ‘unlimited’ characteristic. In order to get used to this structural change in the labor market, the Chinese manufacturing sector is experiencing the spatial fix that Silver talks about in Forces of Labor, as well as the technological fix and the product fix.

Spatial adjustment is when the company moves production to a place where labor is cheaper and where the workers are more easily disciplined. In the era of globalization, the high fluidity rate of capital means that there is an increased flooding of a ‘race to the bottom’, increasing the rate of ‘deindustrialization’ of Western society as well as the fading of the accompanying union movement. In China, even though the centralization of politics means that the organization of union movements is banned, the migrant workers’ ‘wild cat’ method that has grown organically has in recent years put pressure on international capital. Take the example of a big strike in Dongguan which fifty to sixty thousand workers participated in against a Taiwan-funded enterprise, Yue Yuen Industrial (Holdings) Limited, which successfully demanded the payment of over ten years of social security benefits. After this, the company quickened its pace in moving the factory to Southeast Asian countries, and their employees went from 100,000 to 10,000 workers.

Overall, the labor movement in China has been strictly controlled by the government, so its impact is limited, and the main reason why manufacturers focused on export have left China in the last ten years is rising labor costs, the rise in standards for environmental protection, as well as the imposition of tariffs during the China-United States Trade War. In terms of industry categories, the trend for moving to Southeast Asia is quick for textiles and electronics. Samsung had already started, in 2018, to shut down its factories in China, making Vietnam its core base for production. Apple is also pushing its supply chains, for example Foxconn, Quanta, Pegatron and Wistron, to increase their investment in Vietnam and India, especially under the influence of Covid. Thus it was obvious that Apple had a strategy to create another supply chain outside of China, and this lessens the strategic risk of the world’s over-reliance on China’s manufacturing.

On the other hand, in order to maintain a competitive advantage in the cost of manufacturing, in the last ten years China has promoted the idea that international companies should go mid-west, in order to avoid the phenomenon of extreme labor shortage in the east coast area, while at the same time shortening the time-span for wage-increase. Because different parts of China develop at different speeds, there is still surplus labor in the central and western regions, suitable for labor-intensive industries to develop—the Chinese version of the ‘flying-geese model’ in Development Economics. According to this logic, in the past ten years electronic and textiles manufacturing in the central and western regions have developed vastly. For example, Chongqing has already become the world’s largest manufacturer of laptops, Zhengzhou produces half of the world’s iPhones, and Xinjiang has become an important base for the manufacturing and exportation of textiles.

However, speaking of the labor regime, the factories that have moved into the central and western parts of China are highly exploitative. Different to the fluid migrant workers who are attracted to the areas along the east coast, the factories in the central and western areas mainly attract local people, which are limited in number with a high turnover rate. In order to ensure a stable labor supply, companies will rely on the government’s administrative orders for recruitment. And in order to attract investment, the government wants to ensure that the company’s recruitment issues are solved within the agreements made. For example, in Chengdu a portion of the civil servants have to be responsible for some of the recruitment quota for the Foxconn iPad factory, and if they fail they have to go work in the factory. The most extreme case of this was when the education department demanded that vocational colleges send their students to intern at the enterprises or they wouldn’t be able to graduate.

There have been many scholarly as well as journalistic articles written about, exposing these compulsive internship practices as a main source of the labor. Compared to recruiting from society, the costs of having interns is far lower because the enterprise doesn’t need to pay a minimum wage according to labor laws or organise social security. At the same time they can transfer management to school teachers. The students are in a weaker position because they are not training their skills through their internships, instead they could get their pay docked and they may have to work overtime, etc. In this context, forced labor in the Xinjiang ‘re-education camps’ is the extreme version of making students work, and it is all in the name of economic development. The government is not using pricing leverage, but rather administrative orders when it comes to market-based employment to maintain the low labor costs in manufacturing.

‘Machine Substitution’

Technological adjustment points to the enterprise implementing a huge innovation in the process, bringing in technology for increased labor efficiency and changing the way production is organized, for example using robots to solve the problem of decreasing profits as well as labor control. In the history of the development of the auto industry, the manufacturers of the different countries have, on different levels, automated labor-intensive tasks in varying degrees in order to cope with the rising labor costs and the labor movement.

Robotic process automation on the automotive industry. Image by Lenny Kuhne at Unsplash.com under CC license.