Image by L.Filipe C.Sousa, available at Unsplash under CC license.

150 Years of Studying Abroad in China: Three Cases of Study-Abroad Fever

China’s modern history has been shaped by Chinese students studying abroad, but will today’s Chinese students overseas still be able to mold the future of the country?

Quick Takes:

Throughout 150 years of Chinese students travelling overseas for education, rulers in China have always oscillated between two attitudes toward study abroad:

1. A high motivation to learn technologies from the West.

2. Fear that a "virus of political rebellion" will be imported to China through overseas students returning home.

While individual students want to invest in their own lives through international experiences, their fates are always tightly bound to China’s political circumstances.

In the spring semester of 2021, a special moment in my teaching career presented itself: teaching in English to a group of Chinese students who were enrolled in an American university. They could not go to their universities in the US because of the COVID-19 pandemic, so they instead arrived in Shanghai to attend lectures. Twice weekly we met up in a building in a Chinese university to discuss, in English, the history of modern China.

Chinese college students can now complete American university credits without leaving China—something I could never have imagined before COVID-19 hit. This is a good stopgap measure for those who are trapped because of the pandemic and tired of online classes. Still, what is the point of studying abroad without going abroad? I can’t help but ask, will the current study-abroad students, like the generation who preceded them, bring about change in China?

The “study-abroad fever” in modern Chinese history began in 1871. The first group of Chinese students was sent to the US by ship by the Qing government. Over the past 150 years, the educational exchange between China and the West has reached far beyond academia. For younger Chinese, going abroad and staying abroad to experience different cultures has often been more attractive than merely getting a degree from a foreign university. Studying abroad has stirred up ripples in the minds of different generations of students, and set off a continuous chain of thought throughout China.

Learning Advanced Technology From the Barbarians

In the late 19th century, some realists in the Qing government recognized a knowledge gap between China and the West and suggested the policy of “learning advanced technology from the barbarians in order to fight them.” The Qing government led a self-improvement program to learn from Western science and technology, termed the “Westernization movement.” The government invited foreign teachers and consultants to ignite industrial revolution and lead education in China on the one hand, while on the other creating a plan to systematically send Chinese students abroad. The latter was considered the most effective way of learning the secrets of the rich and powerful West.

In 1871, two highly influential ministers, Zeng Guofan (1811-1872) and Li Hongzhang (1823-1901), jointly submitted an initiative to the Qing court. The initiative was titled On Sending Young Men Abroad to Study and argued for a “selection of intelligent youths to be sent to the schools of various Western countries to study military administration, shipping administration, infantry tactics, mathematics, manufacturing, and other subjects.” The two politicians estimated that “after more than ten years their training would have been completed and they could return to China so that other Chinese might learn thoroughly the superior techniques of the Westerners. Thus we could gradually plan for self-strengthening.”

China’s first group of government-sponsored overseas students, attributed Milton Miller, 1872. Image by Courtesy Loewentheil China Photography Collection.

In the United States, this plan was called the Chinese Education Mission. Its implementation was tremendously hard, as conservative forces in the Qing court strongly opposed the plan; there were strict standards for the selection of candidates and traditional Chinese families felt afraid of the cultural differences of foreign countries and hesitated to send their underage sons abroad. In 1872, thirty male teenagers aged 12 to 16 were selected from the more liberal coastal regions to travel from Shanghai to the US by ship. A pioneering move in Chinese history - study abroad for Chinese students was officially launched.

In the next three years, 30 children went to the US each year. These children, who came from the ancient East, boarded their first ever ship to cross the Pacific, took their first ever train to cross the American continent, and witnessed their first telegram transmitting information instantly.

The purpose of the Westernization movement was very clear: to transform certain technologies that were lagging behind compared to the West. This included the Chinese military, transportation, mining and communication. The Qing government stipulated clearly they only encouraged Chinese students to travel abroad to learn different kinds of engineering and military technologies, while avoiding Western music, religion, medicine as well as other knowledge.

Despite these instructions, conservatives who insisted on the superiority of the Chinese culture and system still found the exchange inexcusable. They were concerned that Chinese students, who lived in the US for long periods of time, would be influenced by the West’s religions and cultures and abandon traditional Chinese value systems. These officials repeatedly petitioned the Emperor, narrating the dangers of starting an educational exchange with the West.

Three years later, the Qing government partially caved and decided to no longer send students to the US. However, from 1877 onwards, the Qing government sent out 80 students in batches to the UK, France and Germany to study naval business and gun machinery manufacturing. The difference between them and the students who left for the US was that these students were older, and were „managed” more strictly, so that they would return to China after two or three years to contribute to the navy.

Meanwhile, students who were sent to study in the US were still there and assimilated into local life. Some even cut their long queues, which signified the Qing dynasty, and practiced local sports, such as baseball. Only in 1881 did the Qing court decide that all Chinese students who remained in the US had to return. A New York Times article published on July 23 1881 reported that these students had excellent grades, and about half of them had already qualified for university:

"It is unreasonable to suppose that bright young men like those educated in the United States at the cost of the Chinese Government should content themselves with absorbing the principles of engineering, mathematics, and other sciences, remaining, meanwhile, wholly irresponsive to the political and social influences by which they are surrounded. […] China cannot borrow our learning, our science, and our material forms of industry without importing with them the virus of political rebellion. "

Though these young students did not complete their studies in the US, they were treated coldly once they returned to China. The earliest and most gifted engineers in China were amongst them, however; according to incomplete data collected by Chinese statisticians. About thirty of them worked in telegraph operation, mines, and railroads, including Zhan Tianyou, who would later be dubbed the Father of China’s Railroad. Five people worked in education, for example the inaugural President of Tsinghua University, Tang Guo’an; twenty-four people were employed in diplomacy and administration; seven people in business, and fourteen joined the navy.

And this was only the beginning of China’s study-abroad journey.

China cannot borrow our learning, our science, and our material forms of industry without importing with them the virus of political rebellion. — New York Times, 1881

Tides From the West

At the end of the 19th century, the conservatives gained power in the Qing court. They supported poor farmers from Shandong to launch the largest anti-Western, anti-Christian movement in modern Chinese history, “The Boxer Rebellion.” The so-called Boxers were finally defeated by the Eight-Nation Alliance. Because of the Rebellion, Empress Cixi, the ruler of the Qing government at the time, realized that she only had one way to hold onto her political power: reform. She punished the conservatives heavily, and decided on reform on all fronts, including education.

In 1905, encouraged by reform officials, Empress Cixi declared the abolition of imperial examinations. The imperial examinations had existed for thousands of years, since the Ming and Qing dynasties, as a way to select bureaucrats for government at all levels. It was the only method for countless men to elevate their social positions. With the abolition of this system, young people had no choice but to plan out their lives differently. The Qing government required all regions to set up new kinds of schools, to reform their education to match the West, and to give important positions to students who had returned from studying abroad.

The central and local governments at the time set up scholarships to encourage students to study abroad. In addition, vast numbers of Chinese people planned to study overseas at their own expense, which launched the first study-abroad “fever” in modern Chinese history.

The rise in the craze to study abroad was driven by the Qing government’s policy shift. Empress Cixi’s all-round call for reform created a great number of employment opportunities for gifted scientists and engineers, and the Chinese study-abroad students took this as their guide when they picked their majors. Mechanical engineering, chemical engineering, mining, military, textile studies, agriculture, metallurgy and other practical studies accounted for eighty percent of student enrollment in 1914.

During this time, the conservatives’ fear came true. Chinese people’s ideological values were changed along with the exchange of technology, and Western culture and thought flooded in, influencing multiple generations of Chinese people. Jiang Menglin, who went to the US in 1908, earned his doctorate in Education from Columbia University in 1917, and was President of Peking University from 1919 to 1927. He named his memoir Tides from the West.

Under the impact of this “Western tide,” the study-abroad students cut off their queues, and some converted to Christianity. Others even advocated that the Qing dynasty should be violently overthrown in similar movements to the American Independence movement or the French Revolution. Various students who were studying in Japan translated Western classics from their Japanese translations, so that they could be read in China.

Moreover, young people who advocated French anarchism targeted high-ranking officials in the Qing government and launched many assassination attempts. The revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen, who led the rebellion against the Qing government, was educated in the West and had graduated from a high school in Hawai’i. He lived in Japan for a long time, and was widely supported by the Chinese students who were studying abroad in Japan.

In 1912, China became a republic, and the study-abroad fever propagated by Empress Cixi continued. If you were to travel to early 20th century China in a time machine, it would be as if you walked into a supermarket of thought: anarchism, pragmatism, liberalism, fascism, socialism and Marxism were all on offer, floated over from abroad with the labels Made in USA, Made in France, Made in Germany, or Made in Russia. Intellectuals who returned from abroad criticized traditional Chinese ethics represented by Confucianism, while at the same time using Western ideologies to discuss social reform, cultural renewal and other macroscopic topics. So much so that it caused Hu Shih (1891-1962), who had returned to China after graduating from Columbia University, to decry: “More Study of Problems, Less Talk of ‘Isms’.” In fact, Hu Shih was a fan of John Dewey’s pragmatism, and became a representative of Chinese liberalism in the 20th century, holding the roles of Ambassador to the US and the President of Peking University.

Ambassador Hu Shih and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Image by unknown author available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

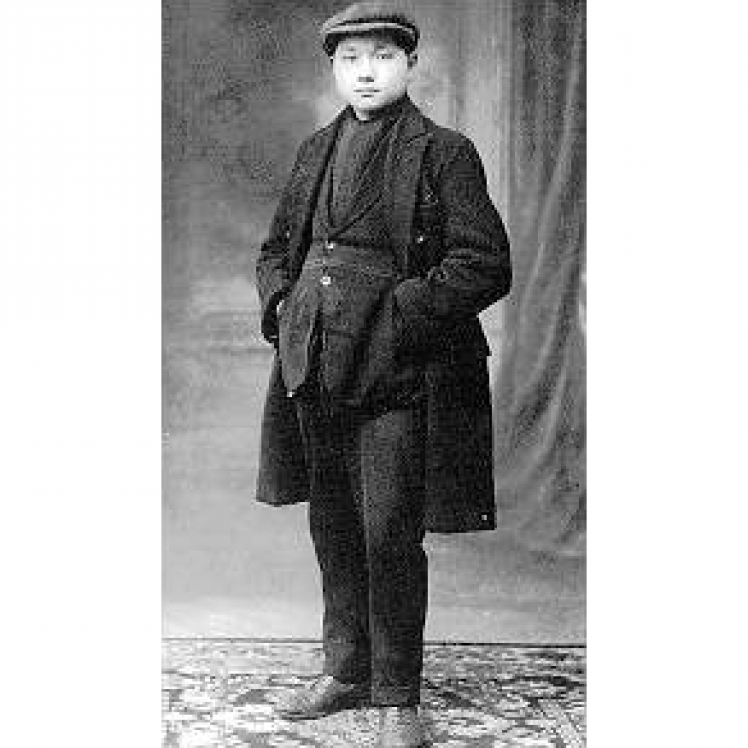

Student Deng Xiaoping in Lyon, France. Image by unknown author available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975), the future leader of the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party), studied Military Affairs in Japan from 1908 to 1911, and his later opponents—including Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping and other leaders of the Communist Party of China—had also studied and worked part-time in France as part of this feverish wave of studying abroad.

Civil war between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party happened between 1927 and 1949. The ruling party Kuomintang had large swarths of returnees from Europe and the US, and the opposing Communist Party of China had many cadres who had trained in Soviet Russia.

In 1949, the Communist Party defeated the Kuomintang, simultaneously ending the “Western tide.” English lessons in schools were replaced by Russian lessons, the country’s gates shuttered, and no one could exit the country freely. The Chinese government only sent a small number of students to Russia and Eastern Europe. But as the relationship between China and Russia worsened, this channel also gradually began to close, and so for most Chinese people who grew up between 1950 and 1970, studying abroad became a foreign concept.

In the early 1950s, many overseas students returned to China after being invited back by the CCP, but not long after they became the target of various political movements. As for how many intellectuals suffered at this time, there are no accurate statistics. Xie Yong, History Professor at Xiamen University, wrote in “An Analysis of the Suicide Phenomenon of Chinese Intellectuals and Other Classes from 1949 to 1976”:

Among the suicides, most were intellectuals who believed in liberal ideals in their early years, with many of the intellectuals having a “study-abroad” background, who have also lived abroad. These individuals had experienced the lifestyle of a free society, and they were not accustomed to the Chinese Communist system just before they moved back to China, or they held on to some beautiful fantasies for the system, which opened up the chasm for what the reality was and the real political situation in the country, as well as what they were expecting and what they were willing to accept. After they realized they were duped, they were unable to extricate themselves from the conflicting feelings that they had suffered for a long time, this, together with the political blows they had suffered, caused them to suffer spiritual breakdowns.

Another “Westernization Movement”

It was not until thirty years later that China reopened its gates. In 1978, on the eve of the resumption of diplomatic relations between China and the US, the two countries held careful negotiations on China’s dispatch of students to the US. According to then US President Jimmy Carter, he was awoken one night by his science advisor Dr. Frank Press, who was in a meeting with CCP leader Deng Xiaoping in Beijing. “Deng Xiaoping insisted I call you now to see if you would permit 5,000 Chinese students to come to American universities,” Press reported to Carter, who did not take the request seriously and replied, “tell him to send a hundred thousand,” before slamming down the phone.

In January 1979, Deng Xiaoping visited the US and signed, with Jimmy Carter, the Science and Technology Agreement to Speed up Scientific Exchanges. At the time, 100 Chinese students resided in the US. By 1999, Chinese students in the US had surpassed 100,000, a figure Carter had casually thrown around twenty years prior. Carter claimed that he once joked to Deng Xiaoping: “I have to make an apology to you, Xiaoping. All of your best students have come to America and will never go back!” To this Deng Xiaoping replied: “That’s a good thing, and it was how I planned it. So many of the Chinese students have landed at MIT, Georgia Tech, IBM, and then they return to China, and with them comes the technology.”

Deng Xiaoping and Jimmy Carter during Sino-American signing ceremony on 31 January 1979. Image by Karl H. Schumacher available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.